Welcome to BlackPast

BlackPast is dedicated to providing reliable information on the history of Black people across the globe, and especially in North America. Our goal is to promote greater understanding of our common human experience through knowledge of the diversity of the Black experience and the ubiquity of the global Black presence.

Honoring Pioneer African American Periodicals

NEWSPAPERS

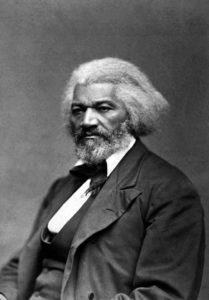

Dating back to Freedom’s Journal, which was started in 1827 by two free Black men: John Russwurm and Samuel Cornish, journalist and editor of the country’s first Black-owned and operated newspaper, African Americans have looked to and trusted Black outlets for most of their news and information about current affairs. The New York-based Freedom’s Journal advocated for the abolition of slavery, as did The North Star, launched by Fredrick Douglass in 1847. During the late 19th and early 20th century, a proliferation of “race” newspapers emerged, which provided a platform for African American thought and political expression.

John Russwurm, Samuel Cornish and Fredrick Douglass Started the first Black-Owned Newspapers in America

The Memphis Free Speech, founded in Memphis, Tennessee, in 1881 by the Reverend Taylor Nightingale of Beale Street Baptist Church, was one. In 1888 the paper became the Memphis Free Speech and Headlight when Nightingale was joined by J. L. Fleming, a newspaperman from Crittenden County, Arkansas. In 1889 the pair invited Ida B. Wells to join the paper, which she did as a partner. Wells was the editor and covered incidents involving racial segregation, violence, and inequality. Fleming was the business manager, and Nightingale was the sales manager.

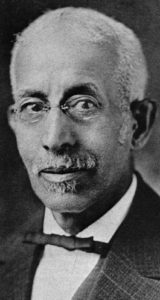

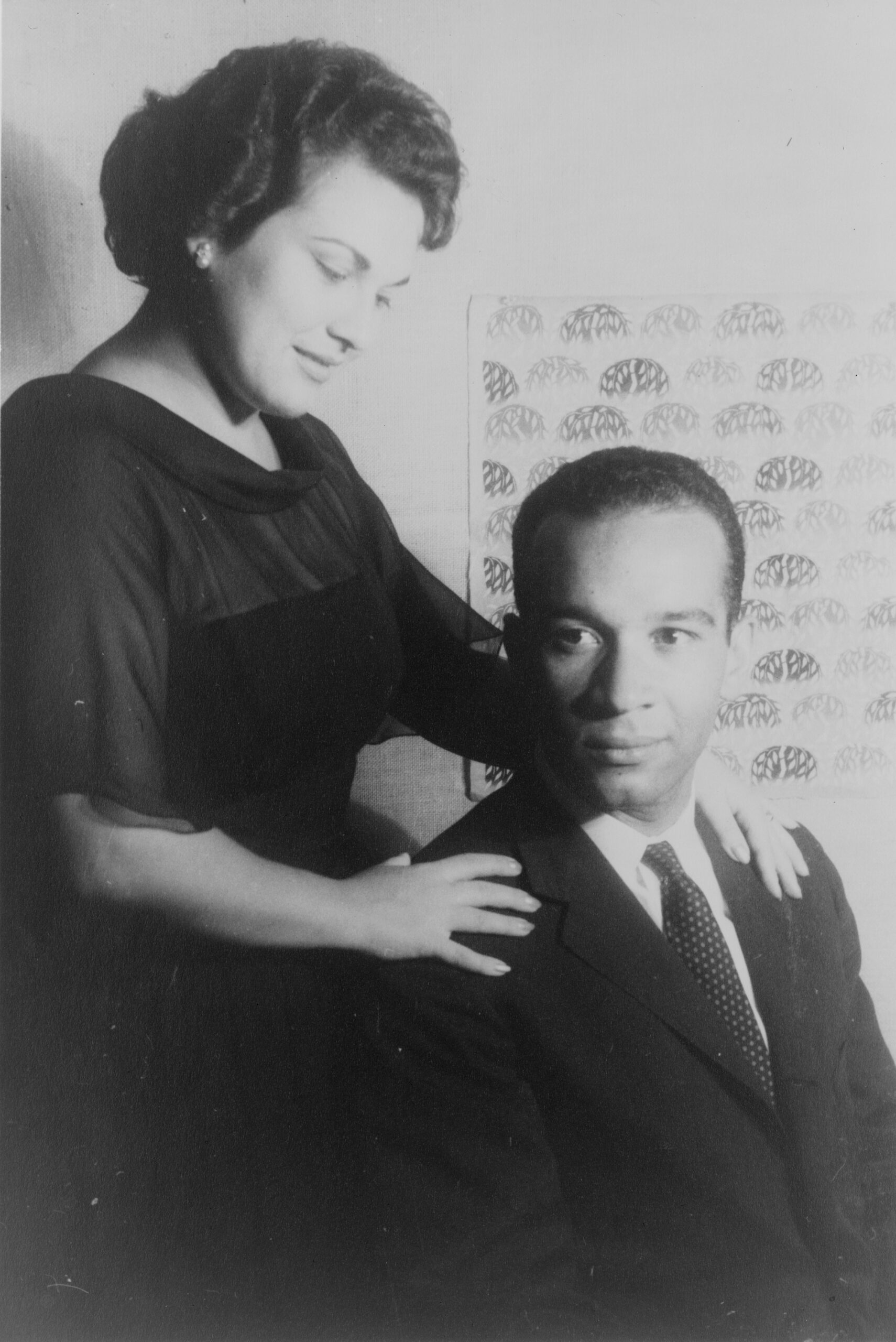

L-R Father and Son, John H. Murphy and Carl Murphy of the Baltimore Afro-American

The Baltimore Afro-American was an essential voice of the African American community in Maryland, and by the 1920s, of the entire east coast. The paper was initially published in 1892 as a weekly four-page news sheet. It promoted Black entrepreneurship, fashion, and achievements and reported births, marriages, and deaths. In 1896 it changed hands, and in 1900, its new owner John H. Murphy joined with George Freeman Bragg, founder of the weekly Petersburg Lancet, which was dedicated to civil rights issues in Richmond, Virginia. Together they published the Afro-American Ledger, which became known simply as the Afro-American following Bragg’s departure from the business in 1915. Mention must be made of Carl Murphy, president and successor to his father, John H. Murphy’s publishing legacy. A brilliant editor, he graduated from Howard and Harvard universities, and was a professor in – and then chair of – the German department at Howard between 1913-1918.

Carl Murphy expanded the paper to nine national editions, published in 13 major cities. At its peak, the Afro-American was publishing two weekly editions in Baltimore and regional weekly editions in all the major destination northern cities for Black migrants from the South, including Washington, DC, and Richmond, Virginia.

Chicago was one of the most important sites of Black relocation. According to its byline, the Chicago Defender, founded in May 1905 by Robert S. Abbott out of his landlord’s kitchen with an initial run of 300 copies and an investment of twenty-five cents, was one of the most influential Black newspapers in the world! In its pages, Abbott actively promoted Black migration to Chicago, publishing accounts of the all too familiar racial atrocities Blacks faced in the South. In 1910 the paper acquired its first full-time paid employee, J. Hockley Smiley, who was instrumental in helping The Chicago Defender attract a national audience and to address issues of national scope (PBS). Perhaps the claim to world supremacy was exaggerated; nonetheless, the Chicago Defender was so influential White Southerners barred its official distribution, leaving Pullman Porters to facilitate its surreptitious distribution throughout the South. The Defender, like the Afro-American, was the voice of the migration and the source of hope for many who sought assistance in finding work, accommodation, and relatives should they move to the city.

In this period, there were approximately fifty Black-owned newspapers in the country including the Los Angeles Sentinel, the Atlanta Daily World, the New York Amsterdam News, the Pittsburgh Courier, and the Norfolk Journal and Guide, with origin stories similar to that of The Chicago Defender. These weekly publications also served to acculturate new residents from the South. They supported the cultivation of Black communal identity across time and space.

Nora Holt, W. E. B. Du Bois, G. James Fleming, Algernon Jackson & Moneta Sleet worked and wrote for the New Amsterdam News.

One such, The Amsterdam News, was started in 1909 by James Henry Anderson with an investment of US$10. He sold the ‘newspaper’ for 2 cents a copy from his home at 132 West 65th Street in Manhattan’s Upper West Side. The growth of the Black community in Harlem helped the paper’s success, and by 1910 Anderson had established offices at 17 West 135th Street; six years later, he moved to a larger space on 2293 Seventh Avenue and, in 1938, moved again, to 2271 Seventh Avenue. In the early 1940s, The Amsterdam News moved to its present headquarters at 2340 Eighth Avenue (also known in Harlem as Frederick Douglass Boulevard).

From their inception in the early 1800s, African American newspapers were in the vanguard of the fight for Black civil and political rights. They challenged the negative portrayal of Black people and encouraged racial pride, self-love, self-help, and entrepreneurship. They advocated for economic equality, integration of the armed forces, and fair housing practices. They mobilized the people in voter registration campaigns and against discriminatory practices by employers: “Don’t Buy Where You Can’t Work” being one such. They appealed to a collective Black remembrance.

Explore the images below and learn more about the history of Black publishers and the newspapers they sponsored. Learn about the contemporary and historical contributions of Black journalists and writers.

MAGAZINES & JOURNALS

Two important radical publications of the early 20th century, and the men who published them L-R A Phillip Randolph, Chandler Owen, and Charles Spurgeon Johnson of the literary magazine, Opportunity.

The Crisis was the official publication of the NAACP. Founded in 1910 by W. E. B. Du Bois to fight against racism. In 1917 A. Philip Randolph and Chandler Owen published the socialist and antiwar Messenger of New York. In fact, during the period, there were only two leftist newspapers, the Messenger and Cyril Briggs‘ the Crusader, founded in 1918.

In 1923 The journal, Opportunity, published by Charles Spurgeon Johnson, appeared. It featured academic discussions of social issues and works by Black creatives of the Harlem Renaissance, which Johnson got by sponsoring monthly literary contests. Countee Cullen, Langston Hughes, and Zora Neale Hurston were among the early awardees.

Opportunity Magazine contest winners included: Countee Culle, Zora Neale Hurston, and Langston Hughes

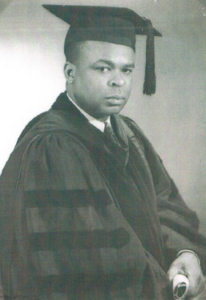

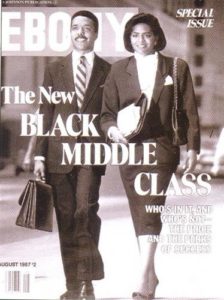

The period following World Ward Two saw the rise of Black monthly and quarterly journals and magazines. Chicagoan John H. Johnson launched the Johnson Publishing Company in 1942 with a $500 loan secured on his mother’s furniture. Three years later, he started publishing Ebony Magazine, described later as “the most successful publishing venture in the history of African American journalism.” In his beautifully expressed publisher’s statement, Johnson professed: “Ebony was founded to provide positive images for blacks in a world of negative images and non-images. It was founded to project all dimensions of the black personality in a world saturated with stereotypes.” (1975)

Modeled on White publications such as Life magazine, which were popular then, Ebony featured Black elite culture. It focused squarely on uplifting the educated, high-achieving, and financially independent. In 1951 Johnson added a pocket-size weekly news digest presenting bite-sized snippets of information about Black people in all spheres of public life for a world he described as “moving along at a faster clip” where there was “more news and far less time to read it.” So popular was Jet magazine that a popular Black entertainer of the 1970s and ’80s called it the “the Negro bible!”

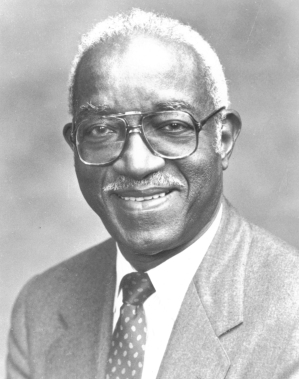

John H. Johnson, Publisher of Ebony and Jet Magazines

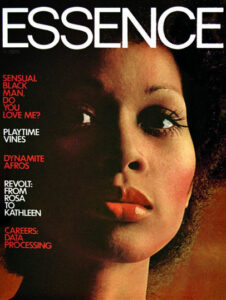

Next to Ebony, another magazine with an enormous cultural impact is Essence magazine, which appeared in the summer of 1970. Dedicated to women, it focused on fashion and beauty with African American and Black models of every shade on its pages and cover. Editor Marcia Gillespie ran the magazine from 1971-1980, succeeded by Susan L. Taylor, who sat in the editor’s chair for 20 years. In the hands of these two visionaries, Essence went from approximately 50,000 copies per month to a US circulation of roughly 1.6 million.

They featured provocative articles on issues affecting the lives of Black women in the USA and, increasingly, globally. Academics Jennifer Bailey Woodard and Teresa Martin note the vital role the magazine has played in promoting the works of Black women writers and supporting Black female journalism in all its political diversity. They write, “Essence serves as one of the best read and most valuable outlets for African American women fiction writers (i.e., Nikki Giovanni, Ntozake Shange, Toni Morrison, Gloria Naylor, Alice Walker, Terry McMillian, etc.), journalists (i.e., Jill Nelson), historians (i.e., Paula Giddings), and essayists (i.e., bell hooks, the late Audre Lourde, Bebe Moore Campbell, etc.). Essence brings renowned writers and up-and-coming, both fiction and nonfiction, authors together in one glossy package that has the potential to be both entertaining and educational.”

Susan L. Taylor, Essence Cover, Richelieu Dennis

Owners Edward Lewis, Clarence O. Smith, Cecil Hollingsworth, and Jonathan Blount, who established Essence Communications Inc. (ECI) in 1968, sold the magazine to Time Inc. in 2005. The magazine returned to full Black ownership In January 2018 after its acquisition by Richelieu Dennis.

Explore Black writers, playwriters and Poets, not all of whom appeared in the pages of the publications mentioned, although but many did.

The End of Affirmative Action in Education

On June 29, 2023, the Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) held that college admission policies at Harvard College and the University of North Carolina (UNC) that included race as a factor were unconstitutional and, therefore, not lawful under the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. The ruling reversed the inclusion of race in college admission policies stemming from a SCOTUS decision in Regents of the University of California v. Bakke in 1978, which involved the admissions policy of UC Davis Medical School.

Background

Affirmative Action grew out of the Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act (CRA). It was extended and reinforced by Executive Orders and the Equal Employment Opportunities Act of 1972. White Americans feeling threatened by the implications of affirmative action determined that it was “reverse discrimination.” Black entrance into professional schools and areas of employment meant increased competition in spaces where Whites had traditionally held power, and this was challenging for most. SCOTUS decided in the Bakke case that while race-based quotas in college admission policies were unconstitutional, using color as one of several determining factors was not.

Following the ruling, many colleges and universities assumed that so long as they only used color as one among many factors in achieving a diverse student population, they were not breaking any laws.

How We Got Here

In 1996 the University of Texas Law School was told to drop ‘race’ as a factor in its admissions process in Hopwood v. the University of Texas Law School. The same year, California voters approved Proposition 209, banning affirmative action in colleges and universities. In 1998, when the ban first took effect, enrollment among Black and Latino students at UCLA and UC Berkeley fell by 40%, according to a Princeton economist.

In 2000 White students denied admissions sued the University of Michigan for violating the 14th Amendment guarantee of ‘equal protection of the law.’ In Grutter v. Bollinger (2003), the court ruled that UoM Law School had a compelling interest in enrolling a racially and ethnically diverse student body because of the educational benefits of diversity. In Gratz v. Bollinger (2003), it was decided that admission to the University through a system of points violated the Constitution’s Equal Protection Clause and Title VI of the 1964 CRA prohibiting discrimination by public or private institutions that receive public funds. In 2016 an unsuccessful attempt was made to overrule the 2003 Grutter decision in Fisher v. University of Texas at Austin.

The Supreme Court cases at the heart of this latest ruling combine two petitions, Students For Fair Admissions, Inc. v. President and Fellows of Harvard College and Students For Fair Admissions, Inc. v. University of North Carolina, et al. Students For Fair Admissions accused both universities of violating the 14th Amendment to the Constitution, specifically the Equal Protection Clause, by discriminating against White and other non-Black applicants. SCOTUS ruled in their favor 6-2 in the first case, and 6-3 in the second.

1997 Franklin Panel

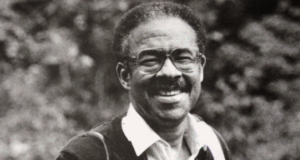

In 1997, the year of the second Million Man March, President Bill Clinton called on eighty-two years old Dr. John Hope Franklin, professor Emeritus at Duke University, to lead the nation in a conversation about race, as the chairperson of his One America Initiative.

Franklin, an elder statesman of the civil rights movement, who contributed to the NAACP‘s brief in Brown v. Board of Education, led a panel which was faced with the difficult task of educating Americans about the “facts surrounding issues of race,” and promoting “a dialogue in every community of the land to confront and work through these issues, to recruit and encourage leadership at all levels to help breach racial divides, and to find, develop and recommend how to implement concrete solutions to our problems.” It struggled at the first hurdle, “how to deal with the contemporary consequences of past racial oppression,” and made no contribution to the debate over affirmative action (Carson, Lapsansky Werner & Nash, 2011).

In a 1993 social and historical commentary, he explains his view, following from W.E.B. Du Bois whom he paraphrases, that “categorically … the problem of the twenty-first century will be the problem of the color line.”

Honoring Educators & Educational Institutions

The outcry over the decision to strike down affirmative action might give the impression that African Americans placed their hopes for education in the hands of White institutions only and that, in the aftermath, the doors of higher education will be closed to Black students forever. Indeed, nothing could be further from the truth.

In the immediate post-Civil War period, when only two predominantly white colleges, Oberlin (Ohio) and Berea (Kentucky), accepted Black students, institutions founded by African American churches, by Southern state governments, and in one instance, the federal government (Howard University) gave African Americans access to higher education. Read our entry on the history of HBCUs, which draws attention to the ‘surge’ in HBCU enrollment after the 2020 summer of Black Lives Matter protests. Who knows what impact this new ruling will have on HBCUs.

Tennis, Anyone?

In 1948 track star Alice Coachman became the first Black woman to win an Olympic gold medal in track and field.

That same summer, Althea Gibson took the national American Tennis Association (ATA) championship title for the second year running (something she would do for the next eight years). According to historian Jennifer Lansbury of George Mason University, the African American elite saw an exceptional talent in Gibson, who she describes as “living a tomboyish existence on the streets of Harlem.” They hoped that she would be the one to break the color barrier and “groomed her to enter and excel in the high-class world of tennis.” Their faith in her paid off. Gibson had “big service and powerful delivery,” which was noted by Ken Love in a story about her victory in the New York Times. “When she hits the ball, it travels like a bolt out of a crossbow,” he wrote. Following her ascension to the pinnacle of the African American tennis community, Gibson broke into the USLTA [United States Lawn Tennis Association] in 1950. At 23, she made her debut at the Nationals (The US Open), and in 1951 became one of the first Black tennis players to compete at Wimbledon and the first to win a Grand Slam, which she achieved in 1956. Gibson won the ladies’ singles title at Wimbledon and the women’s singles at the US Open in 1957 and 1958. In the winter and spring of 1956, she and three other players represented the United States in a goodwill tour of Southeast Asia organized by the State Department.

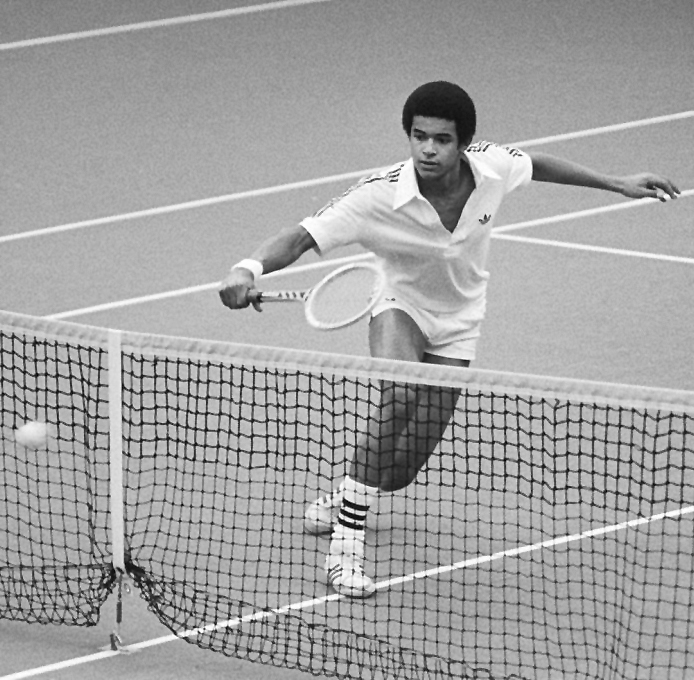

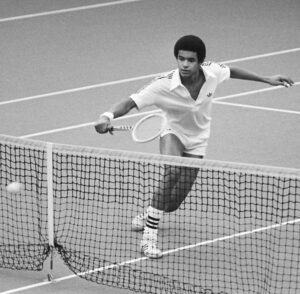

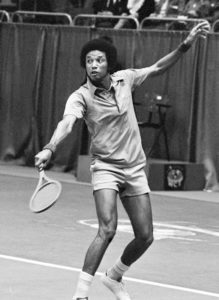

Gibson is but one of a not-too-shabby list of Black women tennis players who’ve dominated the game at one point or another since the 1920s when Ora Washington was the star player in the American Tennis Association (ATA). This Black organization existed alongside the United States Lawn Tennis Association. Since then, we’ve cheered on brilliant female players: The Peters sisters, Zina Garrison, and Naomi Osaka, to name a few. Success in the game for Black men still lags behind that of women, although among two of tennis’ legendary players are Arthur Ashe and Yannick Noah, both of whom won Grand Slam singles title.

In 1963 Arthur Ashe became the first Black player ever selected for the Davis Cup team; he would lead the United States to victory for three consecutive years (1968–70). In 1965, he helped UCLA with the NCAA tennis championship and won the US Open in 1967 and the Australian Open in 1970. In 1975 Ashe won Wimbledon by beating Jimmy Connors. The other much-heralded male tennis star, Yannick Noah, was an eleven-year-old in Cameroon when Ashe discovered him. He was later taken to France to develop his talent. Noah won the French Open in 1983.

BLACK MILITARY SERVICE

Click here to access our page dedicated to the Buffalo Soldiers, the approximately 40,000 black men and one black woman who served in four racially segregated regiments, the 9th and 10th Cavalry and the 24th and 25th Infantry of the United States Army between 1866 and 1944. Their legacy carried forward into World War II as the 92nd Division, approximately 15,000 soldiers whose unofficial name was the Buffalo Division and who served mainly in Italy, and in the 24th Infantry Regiment, about 1,000 soldiers, who fought in the Korean War.

Watch our very own Dr. Quintard Taylor, one of the leading experts on the history of the Buffalo Soldiers, discuss their 19th-century origins and contributions in various theaters of action.

WHO'S NEW ON BLACKPAST?

EXPLORE MORE ...

Our Children's Page

HEY TEACHERS! We’re growing our resources for educators and would like to hear from you about your experiences teaching Black history either in the compulsory or post-secondary sector. What are some best practices you can share? What online and/or physical resources do you find useful. What have been/are the challenges of teaching Black history? Did the pandemic change the environment for content diversity for better or worse? Tag your posts with #BlackPastClassroom and let’s share resources with everyone!