In the following article longtime BlackPast.org contributor and San Diego State University Librarian Robert Fikes discusses African American emigrants to and visitors in Italy.

Since the 1850s, African Americans have gone to Italy as tourists, students, soldiers, writers, musicians, opera singers, social activists, and actors. Many, including Frederick Douglass, Booker T. Washington, Langston Hughes, Richard Wright, Edward Brooke, Dean Dixon, Ralph Ellison, William Demby, and Frank Snowden, have offered insightful observations about the nation’s people and attractions based on firsthand experiences. For most, the stay was of short duration, but a few remained there as permanent residents, relieved of the kind of anti-black racism back home that would have smothered their dreams. Some attained professional prominence that would otherwise have been denied them. Italian fascism and colonial adventurism was upsetting but did not significantly change the widely held perception of a friendly nation that presented opportunities for them to flourish. And there remains the little known fact that African American scholars have written impressively about Italian history and culture.

Enjoying hiatus from oppression in his homeland, on a warm spring day in 1852, David F. Dorr, an octoroon slave from Louisiana, stretched out his body on the banks of the Tiber River, resting after having visited the Vatican and witnessed Pope Pius IX in all his jeweled splendor. Self-confident, literate, and proud of his African heritage, several years later Dorr, now a fugitive ex-slave living in Cleveland, Ohio, reflected on his travels in Europe and the Near East attending his once indulgent master in a memoir, A Colored Man Round the World (1858). His chapters on Italy, focusing on Rome, Naples, Venice, Verona and Bologna, Florence, and Pisa, included a considerable amount of historical context and personal interactions with inhabitants.

Dorr was not the only person of African descent in the 1800s with more than superficial knowledge of Italy’s history, people, language, and cultural attainments. Some spent months or years roaming the peninsula and a few decided to sink roots in Italy. In 1853, celebrated landscape and portrait artist Robert S. Duncanson resided in the American art colony in Rome. He was followed by sculptor Mary Edmonia Lewis who settled in Rome in 1865 and activist-medico Sarah Parker Redmond in 1866 as a permanent resident of Florence. Both were visited in 1887 by Frederick Douglass who found in Italy a place where he could walk “unquestioned among men” and where “the longer one stays, the longer one wants to stay.”

Several Catholic clerics of African descent born in the 1800s are known to have been fluent in Latin and Italian and to have studied and toured Italy. Among them were the brothers Patrick Francis Healy, James Augustine Healy, and Alexander Sherwood Healy. Father Augustine J. Tolton and Julia Anna Cooper wrote on Italian art and toured Italian cities, as did Mary Church Terrell who spoke fluent Italian. In 1910, Booker T. Washington did field research in Italy and found similarities between the plight of that nation’s impoverished classes and that of blacks in the American South. Washington’s ascending nemesis, W.E.B. DuBois, twice visited Italy but had less to say except to condemn its fascist government under Mussolini and imperialist ventures in Africa. Helen Chestnutt was the first among a growing number of classically-trained black educators in Italy. Her The Road to Latin: A First-Year Latin Book, appeared in 1932.

In the years between the two world wars a number of African American artists, entertainers, and members of the literati found their way to Italy, including opera standouts Katherine Yarborough, Lillian Evanti Evans, Roland Hayes, and Marian Anderson; and artists Albert Alexander Smith, Lois Mailou Jones, and James Amos Porter.

On his second trek to Venice in 1924, Rhodes scholar Alain Locke, who had studied the Italian Renaissance at Oxford and made comparisons with the Harlem Renaissance, acted as tour guide for his friend, writer Langston Hughes who extended his stay in Italy. But it was in Genoa that Hughes was nearly assaulted by fascist Black Shirts. More than Italy’s domestic fascism, the big problem during the interwar decades that overwhelmed and poisoned African American-Italian relations was Italy’s conquest of Ethiopia that began in October 1935.

African American participation in World War II was disproportionately concentrated in Italy. It was in Sicily that the famed Tuskegee Airmen first engaged the enemy in combat, later transferring to Ramitelli Airfield near Termoli. In the latter months of the war black troops who comprised the racially segregated 92nd Infantry Division fought alongside Italian partisans against German and Italian units in campaigns in the northern Apennines and the Po Valley.

Interracial romance involving black soldiers and Italian women often resulted in marriages and mixed race offspring. The marriage of future Massachusetts Senator Edward W. Brooke to Remigia Ferrari-Scacco was the most prominent example. Decades later Brooke fondly recalled: “The prejudice Negro soldiers faced in the (American) Army was underscored by the friendliness of the Italians, who were colorblind with regard to race. We were simply American soldiers who happened to be black.”

Of the black military veterans present in post-war Italy was literary critic Hoyt Fuller, translator Ben Johnson, and novelist Richard Wright. Army veteran and celebrated novelist William Demby returned in 1947 to study art history at the Università degli Studi di Roma, worked in the Italian motion picture industry, and lived as an expatriate for decades there with his Italian wife. In Turin in 1952 symphony orchestra conductor Dean Dixon led a performance of Ulysses S. Kay’s Suite for Orchestra with Kay present in the audience, an historic event reported by novelist William Gardner Smith in the Pittsburgh Courier. Also in Italy in the early 1950s was novelist Richard Gibson, then a student and correspondent for the Christian Science Monitor; and poet Owen Dodson on a Guggenheim fellowship.

A photograph of a tall, elegantly dressed black man escorting a comparably well-dressed white woman down the steps of an imposing building, guarded by uniformed Carabinieri, illustrated an article in the Saturday Evening Post in 1956 titled “They Always Ask Me About Negroes.” The article’s author was Howard University classics professor Frank M. Snowden Jr., best remembered for his writings on the African presence in ancient Greece and Rome. The woman in the photograph was U.S. Ambassador to Italy, Clare Boothe Luce who had chosen Snowden, the black man in the photograph, as the first ever black cultural attaché at an American embassy in Europe. No stranger to Italy, Snowden, had written his doctoral dissertation at Harvard University on slavery in ancient Pompeii. Fluent in Latin and Italian, Snowden first studied in Italy in 1938 on a Rosenwald fellowship. He averred: “Italians are even more interested in what I have to say about Americans in general. The fact that I am a Negro is less important to Italians than the fact that I am an American scholar trained in their own classical tradition.”

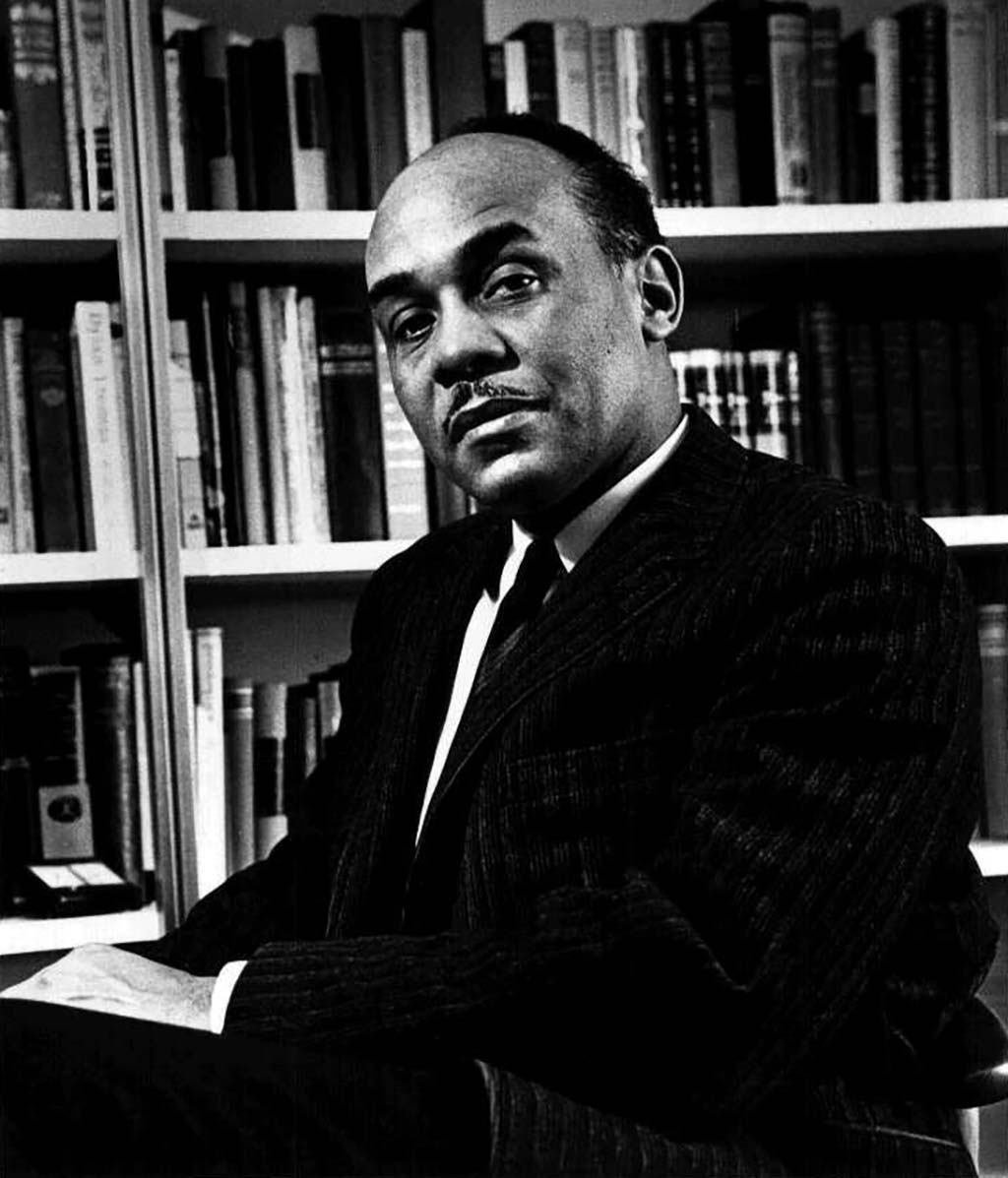

Enigmatic novelist Ralph Ellison, the 1953 National Book Award winner for Invisible Man, was at the American Academy in Rome from 1955 to 1957. While there he deliberately avoided meeting with Snowden and other blacks in Italy. Though Ellison welcomed the publication of his translated masterpiece while in Rome, he made only minimal progress in writing essays and a second novel. Perhaps his own failings partly accounts for his remark to Saul Bellows: “This place has little of the creative tension so typical of New York. You can see more art, hear more and better rendered music….find more interesting writing, there in a day than you can find here.”

Black artists of all types increasingly appeared in Italy in the late 1940s through the 1950s to perform, study, and teach. Among them, operatic stars Ellabelle Davis, Mattiwilda Dobbs, Leontyne Price, all in Milan at La Scala, and baritones Todd Duncan, Robert McFerrin, Sr., and Lawrence Winters concertizing in major cities; dancers Katherine Dunham and Maya Angelou; sculptors John W. Rhoden, Barbara Chase-Riboud who maintained a home in Rome, and Richard Hunt; painters Romare Bearden and Aaron Douglas; photographer-writer Gordon Parks; composers Julia A. Perry and Noel Da Costa; and Eugene A. Graham Jr., an MIT graduate who studied for the doctorate in mathematics at the Università degli Studi di Torino.

Too little attention has been given to the unusual career of actor John Kitzmiller, easily the most recognized African American living in Italy for two decades. The first black actor to win a Cannes Film Festival best actor award in 1957, the Michigan-born decorated ex-Army captain remained in Italy after the war and gradually began working in Italian cinema. Expatriate Harold Bradley, a former pro football player who retired to Italy in 1959 to paint and study art history at the Università per Stanieri di Perugia, became a Rome night club owner, singer, and mostly B-movie actor.

There were numerous African American notables who worked, performed, studied, toured, and taught in Italy from 1960 forward, among them those sponsored by the American Academy of Arts and Letters. The list includes Raymond Saunders, June Jordan, and Faith Ringgold; also Richmond Barthe, Kara Walker, George Shirley, Shirley Verrett, Grace Bumbry, Jessye Norman, Kathleen Battle, Simon Estes, Olly Wilson, Henry Lewis, Toni Cade Bambara, William Melvin Kelley, James Baldwin, Trey Ellis, Joi Derricotte, Lola Falana, Cyrus Cassell, Kobe Bryant, and Andrea Lee who married an Italian man and has resided in Italy since 1992.

Over the past twenty years African American scholars have rediscovered Italian history and culture and have published award-winning books and articles on this. Researchers have charted the increase in the population of black classicists, particularly black Latinists, who include professors Noel Gregson Davis (New York University), Ivy J. Livingston (Harvard University), Shelley Haley (Hamilton College), and Grant R. Parker (Duke University). Experts on the Italian Renaissance are John K. Brackett (University of Cincinnati), Robert R. Coleman (University of Notre Dame in Indiana), and James Carlton Hughes (University of South Carolina); and on modern Italian history, literature and language are Frank M. Snowden III (Yale University), Raymond Fleming (Florida State University) Dwayne Woods (Purdue University), Shelleen Greene (University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee), Ayana O. Smith (Indiana University), Kenise G. Lyons (Catholic University), and Jessica T. Greenfield (University of North Texas).

The clear majority of African American expatriates and extended-stay visitors were not in Italy to escape their blackness, nor did they pretend to be from some place other than the United States. Typically, they sought the company of other blacks and kept in touch with friends and relatives back home. Prior to 1970, some found relief from racism in America. For others both before and after 1970, they came and often stayed because they were attracted to aspects of Italy’s history and culture, believed there were better opportunities for professional advancement abroad, or a combination of both reasons.

Compared to other locations abroad, Italy offered a set of inviting particulars to African Americans including a mild climate, scenic landscape, racial tolerance, slower pace of life, and a highly developed culture of art and music. Collectively that added up to a long-standing, positive perception of a country considerably more attractive to some of the most talented and ambitious among them. With this in mind, perhaps we can begin to comprehend the great anticipation Frederick Douglass experienced, like so many others, while traveling down through northern Italy approaching the Eternal City when he wrote: “All that one has ever read, heard, felt, thought, or imagined concerning Rome comes thronging upon my mind and heart and makes one eager and impatient to be there.”