The New York City Draft Riots remain today the single largest urban civilian insurrection in United States history. By the start of the Civil War in April 1861, New York City, New York Mayor Fernando Wood called for the city to secede from the Union and join the Confederacy, but the response from most New Yorkers was unenthusiastic. Nonetheless, two years later when the U.S. government instituted the first military draft, anti-government sentiment particularly among the city’s large Irish-born population, grew quickly. One could escape the draft by paying a $300 fine (about $5,500 today). The rich were able to afford the fines, while the disenfranchised and poor white men, who in New York City were often Irish, were forced to enlist because they were frequently the sole source of income for their families.

When the draft came to New York City in July 1863, anti-government anger turned to anti-government and anti-black violence. The anti-black violence was driven by the resentment that the Irish would have to compete with freedpeople for jobs in the city because the Union had embraced emancipation.

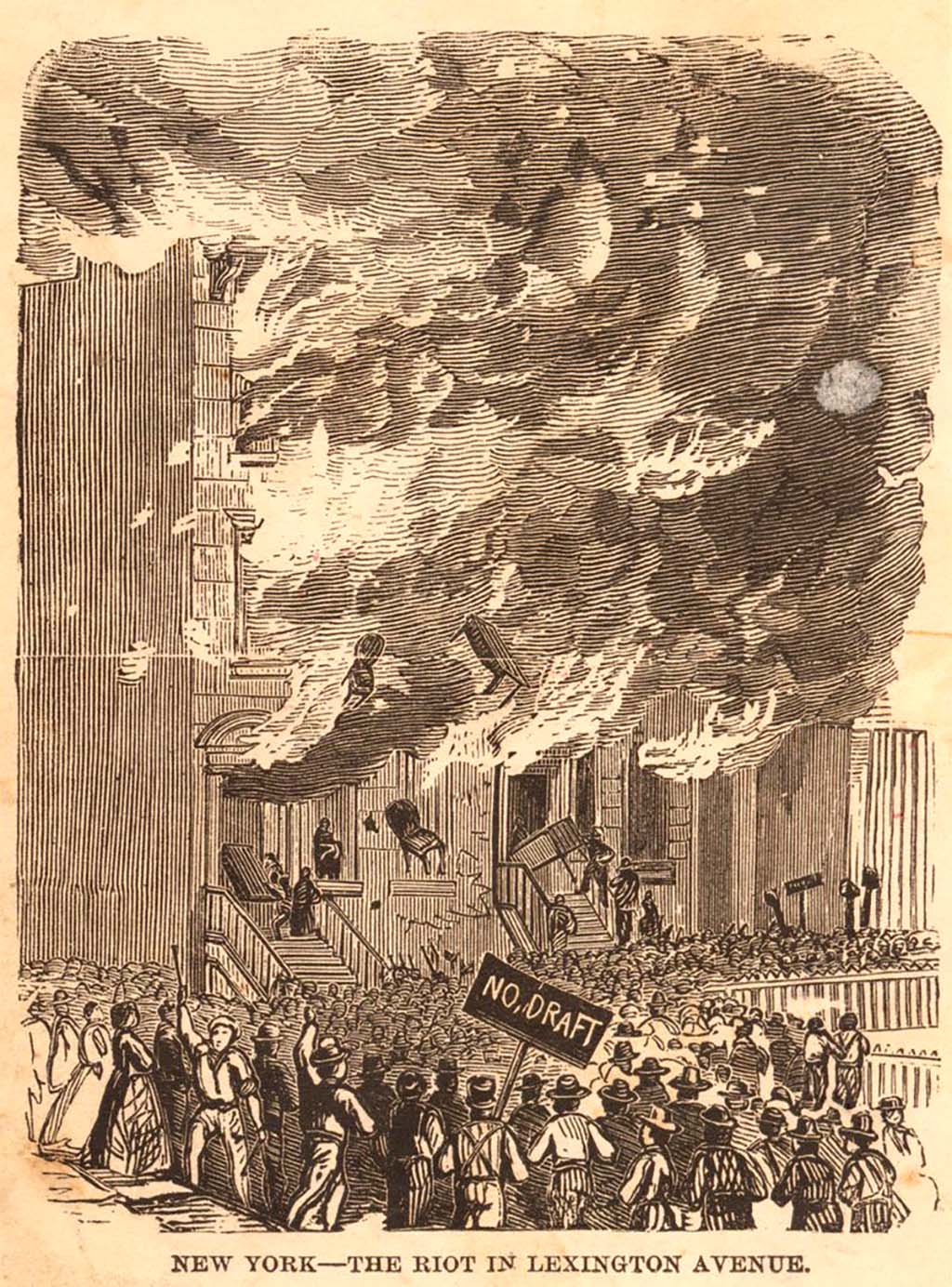

On the first day of the draft, July 11, the city was relatively quiet. However, by day three, July 13, tensions boiled over. Volunteer firefighters from Engine Co. No. 33, were known for their violent nature. Angry at their commissioner, they set fire to their own company firehouse which attracted an angry mob. Led by the firefighters, the mob continued down 3rd Avenue, ransacking and burning businesses in their wake. They focused on those enterprises known to employ African Americans including Brooks Brothers, Harper’s Weekly, Knickerbockers, and other wealthy businesses. They also attacked the homes of prominent white abolitionists. When the mob reached the Colored Orphans’ Asylum, filled with mostly women and children, it began looting the building before setting it on fire. The 200 children inside were led out of the back by their benefactors and taken to safety.

There were many accounts in New York City newspapers of black individuals killed during the riot. Although there were an estimated 663 deaths, only 120 were reported to the police. Of those, however, 106 were African Americans. One account of Ebrahim Franklin’s death was typical. Franklin was in church, praying. He was a disabled man who made his living working as a carriage driver. He lived with his elderly mother whom he supported. The mob reached him just as he was rising to his feet from his prayers and beat him to his death. They then dragged him outside and hung him in the church yard in front of his mother. Finally, they mutilated his corpse.

Although the Union had won two major victories over the Confederacy at the Battle of Gettysburg in Pennsylvania and the Siege of Vicksburg in Mississippi on July 3, President Abraham Lincoln was forced to send 4,000 Union troops to stop the violence sweeping across the city. With the arrival of the troops, including some who had fought at Gettysburg, the violence ended on July 16. One of the ringleaders, John Urhardt Andrews, was arrested and jailed for his role in the riots. Several arrests were made, but there were no other convictions.