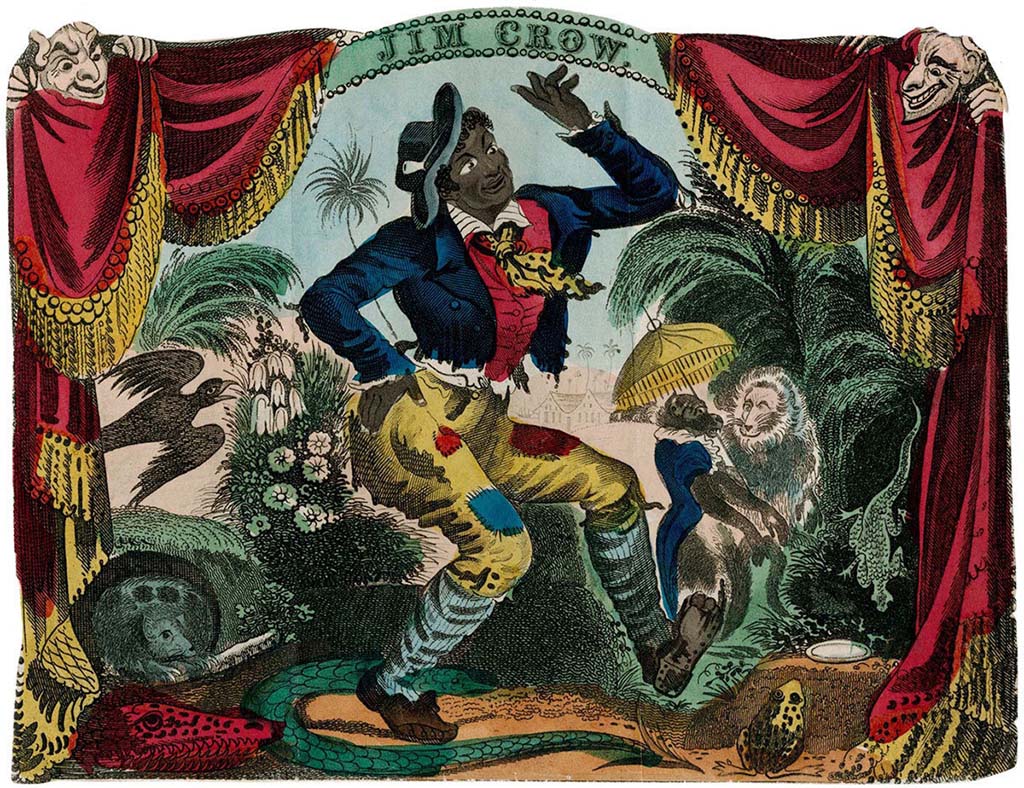

The term Jim Crow originates back to 1828 when a white New York comedian, Thomas Dartmouth “Daddy” Rice, performed in blackface his song and dance that he called Jump Jim Crow. Rice’s performance was supposedly inspired by the song and dance of a physically disabled black man he had seen in Cincinnati, Ohio, named Jim Cuff or Jim Crow. The song became a huge hit in the 19th century and Thomas Rice performed it across the country as “Daddy Jim Crow,” a caricature of a shabbily dressed African American man.

Jump Jim Crow initiated a new form of popular music and theatrical performances in the United States that focused their attention on the mockery of African Americans. This new genre was called the minstrel show. Jim Crow as entertainment spread rapidly across the United States in the years prior to the Civil War and eventually around the world. An example of this influence came when the United States’ special ambassador to Central America, John Lloyd Stephens, arrived in Merida on Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula in 1841. Upon his arrival a local brass band played Jump Jim Crow mistakenly thinking it was the national anthem of the United States. The popularity of Jump Jim Crow and the blackface form of entertainment also prompted many whites to refer to most black males routinely as Jim Crow.

Eventually the term Jim Crow was applied to the body of racial segregation laws and practices throughout the nation. As early as 1837 the term Jim Crow was used to describe racial segregation in Vermont. Most of these laws, however, emerged in the southern and border states of the United States between the years 1876 and 1965. They mandated the separation of the races and separate and unequal status for African Americans. The most important Jim Crow laws required that public schools, public accommodations, and public transportation, including buses and trains, have separate facilities for whites and blacks. The facilities established for African Americans were always far inferior to whites, and reinforced their poverty and political exclusion. These laws also generated a decades-long struggle for equal rights.