Few people realize that the percentage of people of African ancestry in the South American nation of Colombia (7%) is slightly more than half the percentage of people of African ancestry in the United States (13%). Yet we know even less about the origins of that African population. In the article below, Eduardo Dawson, a PhD. student in history at the University of Notre Dame, explores that history.

The experience of African peoples in the region that would become Colombia began in the mid-fifteenth century. Given blacks’ Old World presence in the Iberian Peninsula as servants and auxiliaries to Muslim rulers, they not only played a role in building New Granada and the surrounding imperial zones through slave labor, but also accompanied Spaniards as conquistadores in the Caribbean and South America. These hispanized blacks (ladinos) spoke the language of Christopher Columbus, Hernan Cortes and Francisco Pizarro; the continental Africans (bozales) who later came to the New World would ensure that Spain’s ideological and political economy agendas were carried out. These two groups of Africans can be identified as the ancestors of today’s Afro-Colombian population.

Several decades after Columbus’ discovery, a band of explores founded Colombia’s first colony named Santa Maria on the northern coast of Colombia. In 1533, Cartagena de las Indias was established by Francisco de Quesada with the help of a large number of Africans. The port city was considered to be superior to Santa Maria because of its strategic location as an access point to the land’s interior and the isthmus connecting South and North America. During these early stages of colonial development, Colombia and Venezuela were placed under the colonial authority of the captain general of Nueva Granada. Caracas maintained an autonomous administrative position and the lower southwest corner of Colombia stretching from Cali to Popayán was placed under Quito’s jurisdiction until New Granada became a viceroyalty in 1717.

In search of the fabled “men of gold” who had gained distinction in Europe’s idealization of El Dorado, Spaniards arrived on the northern part of South America eager to extract gold and other precious stones indigenous to the region. During the primary stage of the conquest, Spanish officials relied on the encomienda system to organize indigenous labor. The routinized labor structure placed native people under a Spanish patriarch to whom they would pay tribute in return for colonial social benefits such as Christian indoctrination. During the course of the sixteenth century, the encomienda system struggled to serve Spanish appetites for gold, especially since the indigenous population, unlike their African counterparts, was not immune to Old World diseases such as smallpox and measles. Estimates suggest that as much as 95% of the indigenous population died as a result of the European conquest. It was under this labor shortage and desire for increased extractive capacities that Spanish governors operating in the Americas began to demand that the Crown send continental Africans to the many gold mines found in Colombia’s river valleys.

Under an official proclamation from Charles V in 1518, Africans originating from West Central Africa (most notably the Congo and Angola) were sent to supplement Indian labor and give the Crown a coerced labor force to replace the declining Indian servile population. As alluded to earlier, slaves that arrived in Latin America from 1500-1520 were mostly pre-Hispanicized ladinos who had lived with Spaniards since the Muslim occupation of the eighth century. Several chronicles suggest that these privileged blacks had been overindulged by Spanish acculturation and similar to many Iberians, could not be entrusted to produce significant economic output in the new colonies. Accordingly, the demand for bozales relied on the prerequisite that they spoke no European languages and they would be recognized for the skills they had learned as African agriculturalists.

Although the traditional culture of these people was shattered first by enslavement on the African continent and the subsequent horrors of the Middle Passage voyages, they were quickly recategorized by their new Spanish colonial rules when they arrived at the port of Cartagena during the sixteenth century. They were now divided into three ethnolinguistic categories: those originating from Upper Guinea (currently Senegal to Liberia), Lower Guinea (current Ghana to Nigeria), and the Angolan Coast (contemporary Congo and Angola). Recent data clearly delineates the genealogy of today’s Afro-Colombians as it likewise separates the African offspring into two distinct groupings. Those living north of the Cauca Valley, along the country’s Caribbean and Atlantic coasts, descend from the ethnic groups in today’s Guinea-Bissau and Sierra Leone. Africans in the Cauca Valley and southwestern tip of Colombia descend mostly from Bantu speakers originating from in and around the Congo. Southern Bantu speakers were the African men esteemed for their physical ability to work in harsh jungle climates and the Pacific mines that surrounded Popayán.

These initial bozales arriving in Colombia from 1533-1580 maintained an unsteady relationship with Spanish colonial officials. They rebelled frequently and, in the process, founded the first independent African communities (palanques) in the Americas. Less than a decade after the founding of Santa Marta in 1525, Africans had launched an attack against Spanish leadership, causing heavy disruptions and the eventual downfall of Colombia’s original colony. As blacks moved into the interior and down into Popayán, numerous uprisings ensued. In 1545, 1555, 1556, and 1598, Africans staged revolts that involved the complete destruction of several mining sites, the conquest of white inhabited areas, kidnapping of indigenous subjects, and the construction of independently thriving communities. Among the most recognized of these “runaway communities” was the palanque San Basilio. At this site, Spaniards staged several unsuccessful attempts to regain that territory but were met with staunch opposition from Africans who were unwilling to pass their lives under imperial labor routines. Thus, Spanish elites were eventually forced to grant political pardons for the establishment of independent African authoritative zones. To this day, the African descendants in the San Basilio region boast a rich cultural heritage.

Although the early and evolving history of blacks in Colombia was rife with political instability, many African slaves spent their lives working indefatigably under Spanish-Catholic normativity. Unlike the black servile populations in most New World colonies who became agricultural laborers, the vast majority of African workers in Colombia were gold miners. Many were sent to the Cauca Valley around the lush riverbeds that flowed in and out of Popayán. As significant gold reserves were discovered in Colonial Colombia, the Spaniards crafted a plan to pay off their debt from successive European wars using this precious metal. In the mines, Africans were forced to labor under brutally harsh conditions to procure precious metals for the Spanish Crown. By 1540, they, along with their Incan counterparts, were producing upwards to 30,000 gold pieces annually. In 1559, historians of New Granada (Colonial Colombia) noted that 6,000 Indians and 300 blacks worked over 240 days each year and gathered roughly 195,000 pieces of gold.

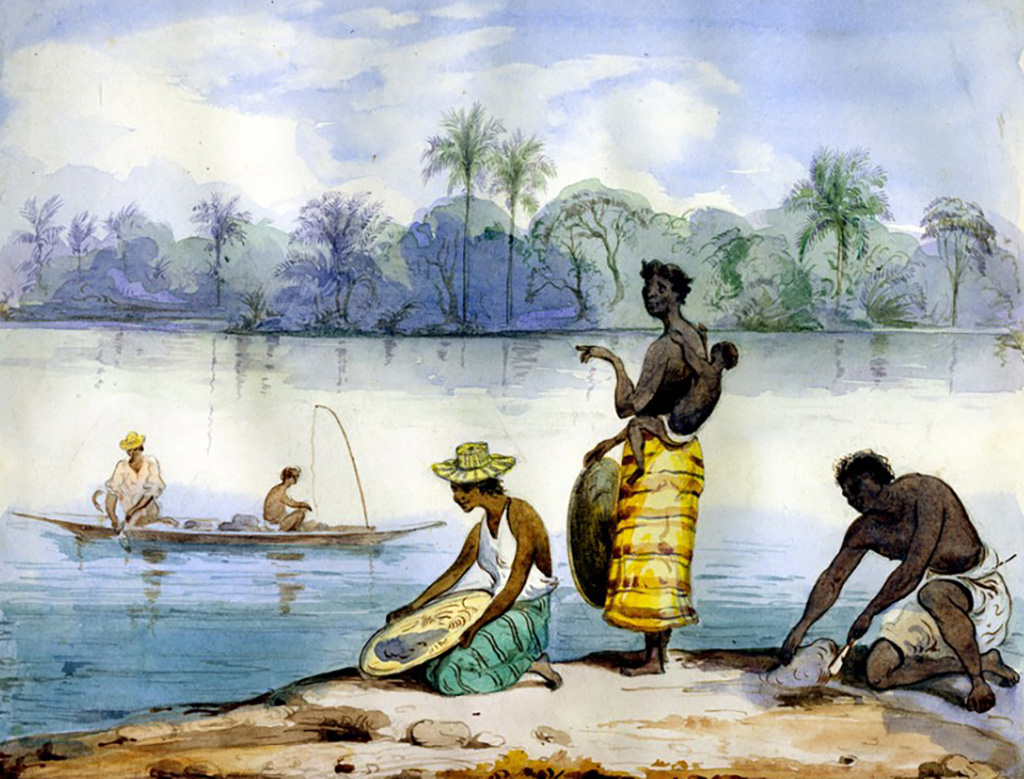

As gold miners, Africans were to be found all throughout Colombia’s western coastal regions in the highlands and in the low riverbeds. This process involved their learning the delicate process of locating and panning rocks, grinding individual stones against other stones and rinsing them to purify the resulting gold pieces. By the later eighteenth century nearly 5,000 Africa slaves were in Popayán and the neighboring region of Barbacoas laboring in the mines. This number surpassed 6,000 by 1788. Slightly north of Popayán, in Chocó and in the Antioquia regions of Colombia, thousands of Africans were also noted for their instrumental role in extracting the metals that gave the region its value to Spanish monarchs.

Africans in the southwest and northwestern regions of Colombia worked in gold mines until well after the official abolition of slavery by now independent Columbia in 1851. This continued role in mining even into the 19th Century relied chiefly on the region’s continued abundance and purity of its opulent gold deposits and the availability of African servile labor. Although Colombia was also the site of sugar fields, cultivation of that commodity did not rival sugar production in Brazil or the Caribbean islands. Thus, the evolution of slavery in Colombia was unique because of the value and prestige of its native commodity—gold—and due to the kind of labor involved in extraction. The allure of gold to the imperial treasury surely differed from Mexico’s wheat production and the olives and grapes cultivated in Peru. Moreover, the technical skills involved in metallurgical extraction differed from the carpentry, tailoring, and bricklaying that Africans were called to do in Mexico. By and large, blacks in other colonial Latin American locales didn’t experience the danger, or pleasures, of churning out gold pieces with technical specificity. Although the work Africans did in Colombia was highly valued because of the commodity they produced, the struggle to honor black lives with equal value was largely neglected in the colonial environment.