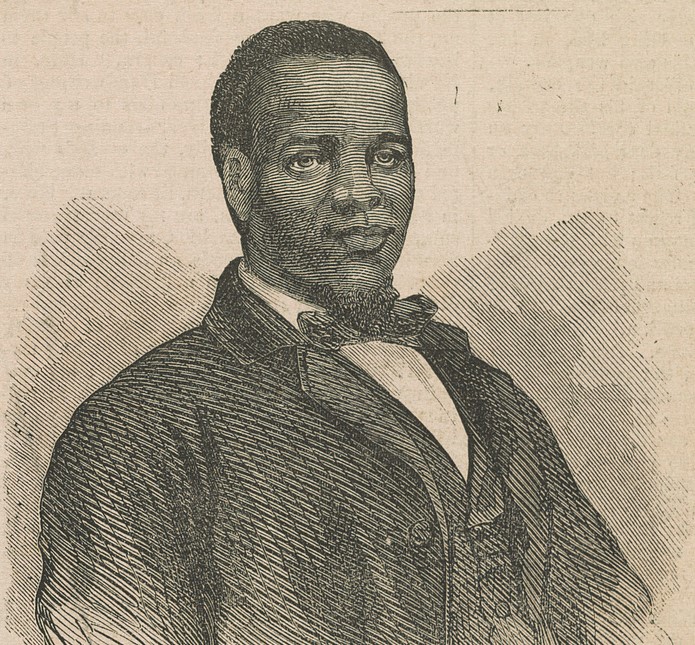

William A. Jackson briefly gained notoriety in the early years of the Civil War as an escaped slave and spy. When the Civil War started, Jackson was held in bondage in Richmond, Virginia where he worked as a messenger in the courts and also drove a coach. In 1861, Jackson’s master G.W Jones hired him out to Jefferson Davis, the president of the Confederate States of America, to be his coachman.

In May of 1862, Jackson found out that Jones was planning on selling him South. Despite the fact that he had a wife and 3 children, Jackson decided to escape to Union lines like many enslaved people before him at that point in the war. When he arrived behind Union lines, he caught the attention of Union commanders due to his relationship to Jefferson Davis. Jackson shared a great deal of information about the low morale of Southerners, even the Davis family itself.

After escaping to Union lines, Jackson became a celebrity in abolitionist circles, offering public lectures. In a speech he delivered in Boston he described escape from slavery, his early life and how he learned to read. The abolitionist newspaper, The Liberator reported that Jackson spoke in the Boston lecture about how enslaved people were able to obtain information about the War’s developments. Jackson also reassured his audience that slavery had prepared Black people to care for themselves and he opposed the idea of colonization for newly freed slaves. Jackson himself claimed that he tried to join a regiment of Black soldiers raised by Governor Edward Sprague in the summer of 1862, but was unable to fight since the United States was not yet enlisting African Americans. Jackson’s talks influenced the debate in the North about the policy of the Federal government toward enslaved Black people.

Jackson also traveled to England to lecture about his experiences. While he was in England, he was a guest of noted abolitionist George Thompson. The Liberator reported that Jackson audaciously wrote Jefferson Davis a letter from London that he could not be with the Confederate President for the upcoming Christmas holiday. Because Jackson was a hired slave, Davis forfeited a sizable deposit to G.W. Jones. William A. Jackson remained in the United Kingdom until 1863. He was disappointed when he learned of the considerable English support for the Confederacy and returned to the United States where he continued giving lectures.

Not much information is available about Jackson’s life after the Civil War. A Vermont newspaper reported that he had enrolled at Pierce Academy, a New England preparatory school to prepare for college, but there is no other evidence of that. After that report Jackson disappears from the public record.