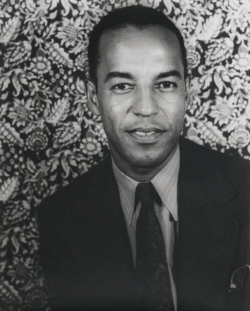

Born in Bay St. Louis, Mississippi in 1901, Richmond Barthé moved to New Orleans, Louisiana at an early age. Little is known about his early youth, except that he grew up in a devoutly Roman Catholic household, he enjoyed drawing and painting, and his formal schooling did not go beyond grade school. From the age of sixteen until his early twenties, Barthé supported himself with a number of service and unskilled jobs, including house servant, porter, and cannery worker. His artistic talent was noticed by his parish priest when Barthé contributed two of his paintings to a fundraising event for his church. The priest was so impressed with his art that he encouraged Barthé to apply to the Art Institute of Chicago in Illinois and raised enough money to pay for his travel and tuition. From 1924 to 1928, Barthé studied painting at the Art Institute, while continuing to engage in unskilled and service employment to support himself.

Even though he mainly studied painting, Barthé’s talent as a sculptor was recognized by his fellow students and local critics in Chicago. In 1928, he put on a one-man show that was sponsored by the Chicago Women’s Club. He eventually moved to New York City, New York, locating his studio in Greenwich Village and creating art – and socializing – with central figures of the Harlem Renaissance, including Langston Hughes, Alain Locke, Augusta Savage, and Carl Van Vechten. While he rejected the circumscription of his art within racial boundaries, his most well-regarded work had a strong racial content. Feral Benga and African Dancer, the latter of which was purchased by the Whitney Museum of American Art, celebrated the black body and African culture, while The Mother contemplated the horrors of lynching. Of particular inspiration to Barthé’s art was the black male body, a reflection of his comfort with his homosexuality, according to one of the foremost scholars of Barthé.

Barthé continued to create sculpture well into the 1960s, some of which was commissioned as public art. He sculpted an American eagle for the Social Security Building in Washington, D.C. and a bas-relief for the Harlem River Housing Project. In 1949, the Haitian government commissioned him to create monuments to the revolutionary leaders Toussaint L’Overture and Jean Jacques Dessalines in Port-au-Prince. In addition to spending time in Haiti, Barthé lived in Jamaica before returning to the United States and settling in southern California. He died in 1989.