In their latest book on the Black soldiers who helped build the Alcan Highway during World War II, authors Christine and Dennis McClure encountered a story of injustice in the frigid north. See a description of their new book, A Different Race, to get a glimpse of a little-known and unfair court-martial of ten Black soldiers in 1943.

In the late 1930’s the Roosevelt Administration turned its attention to potential military threats. Planners in the War Department looked at Alaska’s Aleutian Island chain and worried. The string of islands curves like a slender sword south and then west eleven hundred miles into the North Pacific, and the islands at the end of the string lie perilously close to Imperial Japan. The situation posed two enormous strategic problems for the United States. First, the islands offered the Japanese fifteen thousand miles of undefended coastline. Second, no transport route other than the sea existed between the contiguous lower 48 states and the Alaska Territory. They couldn’t possibly get enough men, equipment and supplies to Alaska to defend it. To counter that threat, the Army and the Navy needed a land route from the lower 48.

On December 7, 1941, Pearl Harbor turned concern to panic. The Army Corps of Engineers dispatched Colonel (soon to be General) William Hoge north to figure out how to build 1,600 miles of Alaska Highway through the rugged and remote subarctic north of Canada and Alaska in eight months. They originally planned to send him four regiments–the 35th, the 340th, the 341st, and the 18th. but when Hoge examined the situation he realized he would need three more. The Corps had no more white regiments, so they reluctantly added three segregated Black regiments to the lineup—The 93rd, the 95th, and the 97th. Altogether about 11,000 soldiers worked through the spring, summer and fall of 1942 to build the original Alaska-Canadian (ALCAN) Highway.

Our book We Fought the Road told the story of the construction of the Highway and the racism that contaminated the epic project. The book focused on the soldiers of the segregated 93rd Engineering Regiment and their heroic efforts in Yukon Territory. Epicenter Press released the book in 2017, on the 75th anniversary of the Highway Project, and we headed back to Canada and Alaska on a publicity tour.

We traveled up the Highway from its origin in Dawson Creek, British Columbia to its end in Delta Junction, Alaska, and then north to Fairbanks, Alaska. As we traveled south from Fairbanks through present-day Alaska to Anchorage and then on to Valdez, we heard stories about the segregated 97th Engineering regiment–the soldiers who built the northernmost portion of the Highway, the portion in Alaska.

The runup to World War II had yanked thousands of young Black men from small towns all over the South into the Army. Most of the soldiers that came to the 97th at Eglin Field in Florida were from the Carolinas and Georgia. In April 1942, the Army dispatched the regiment from Eglin Field in Florida to combat in Alaska Territory. They fought the hostile geography and bitter cold of the subarctic north instead of enemy soldiers but make no mistake, the Army dispatched the 97th to its own form of combat.

The 97th had come to Alaska Territory through Valdez, Alaska, and when we stopped at the library/museum there, Chris found a treasure trove of information in the library’s local history room about Valdez and the Black soldiers.

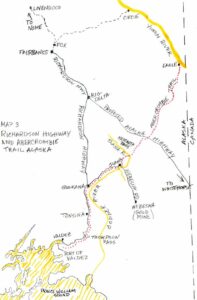

The soldiers of the 97th had, had to build a road for themselves to get from a point north of Valdez to their starting point on the Alaska Highway. We decided to follow that road. Today it’s called the Tok Cutoff.

The road got our attention for several reasons. First we could see no reason for building it in the first place. An existing road, the Richardson Highway, connected Valdez to Fairbanks. On the way it passed through the little community called Big Delta where the Corps planned to end the Highway. Future convoys could use the Richardson from there on up to Fairbanks. Why not just send the 97th up to Big Delta and let them work south from there.

The unfortunate answer gradually became clear. The Richardson Highway, dotted with roadhouses and small communities, is the path of civilization through central Alaska. Determined to keep their Black soldiers as far from white civilians and Alaska natives as possible, the Army Generals decided to get them off the Richardson and out of sight as soon as they could.

To that end they sent white civilian contractors up the Richardson to Big Delta with instructions to build Alaska Highway from there south along the Tanana River. The Black soldiers of the 97th would meet them at a spot on the river now known as Tok. There, safely distant from Alaskans, the Black soldiers of the 97th would take over and build the Highway south to the Canadian border where they would meet the all-white 18th Engineers coming north through Yukon Territory.

To get to Tok, the 97th would follow an abandoned pack trail seventy miles through the Alaska Range Mountains and over the continental divide. The old trail couldn’t possibly accommodate bulldozers and trucks. In effect the 97th had to build seventy excruciatingly difficult miles just to get to their starting point on the Alaska Highway at Tok.

Years and technology have rerouted much of the old road, bypassing the most difficult and dangerous sections the soldiers had to deal with. But driving slowly, looking around, stopping to talk with local residents who had time for us, we began to realize we might be driving into our next book.

One story we heard in bits and pieces. No one seemed to know details. But there had been a mutiny among the troops in Alaska, there’d been a court-martial, and clearly most of the story tellers favored the mutineers.

What we had seen and heard, kicked Chris into gear as soon as we got home. Once again we found ourselves making the rounds of the archives. The court martial story turned out to be true and we found the whole record of the investigation and trial at the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) in St. Louis, Missouri. A white captain, Walter Parsons, had defended the men and we went looking for descendants who might know something about him. Parsons’ oldest son lives in the Outer Banks of Maryland, he has a garage full of paper and memories his father saved and he gave us full access. We spent a week in our camper at a nearby state park making copies.

In the end our second book, A Different Race, released in January 2021, became the telling of this story including the court-martial.

Out of Valdez the 97th would defend their country by gouging a highway through mud and mountains, but the color of their skin obsessed their commanders, thoroughly polluted planning and execution for these soldiers.

Despite challenges from Army commanders, the young soldiers quickly turned into expert road builders and performed heroically. They plunged through Alaska’s coastal mountains, to the Tanana River then south through muskeg and permafrost to the Canadian border. They then crossed the border to bail out the struggling white soldiers of the 18th Engineers.

The Highway behind them, the Black soldiers of the 97th moved into tents to endure the frigid subarctic winter of 1942-1943. And while they endured, their commanders, worried. The Army had long trained white officers who commanded Black men that these soldiers couldn’t be trusted and needed especially tough discipline. In the rush to complete the road, some military routines had been ignored and now the Army looked for ways to restore strict discipline over the idle soldiers.

On March 29, 1943, a frigid day in Alaska, 34 degrees below zero, young white lieutenant DeWitt C. Howell ordered ten Black soldiers into the back of an unheated truck for a life threatening 130-mile trip from the encampment on the Big Gerstle River to Fairbanks. The soldiers knew the trip could kill them and the frostbite would certainly maim them. They resisted, tried to talk the lieutenant out of it, and finally moved slowly and reluctantly toward the truck bed. Infuriated at the challenge to his authority, Lieutenant Howell canceled the trip and ordered the ten men arrested and confined to quarters.

The Army transported the ten men to the stockade in Whitehorse, Yukon and formally charged James Heard, Willie Calhoun, James V. Hollingsworth, Josh Weaver, Robert M. Rucker, Sims Bridges, Lee I Ratliff, Willie Howell, Warren Lindsey, and Eugene Fulks with the most serious crime a soldier can commit—Mutiny. After weeks of shuffling paper, the court martial convened on June 5, 1943.

In 1943 the system of military justice offered an extremely powerful weapon to senior commanders—the general court martial. General James A. O’Conner, senior commander on the Highway, used this weapon to set a virtuous example for his Black enlisted men. Prosecutor, Captain J. Ward Starr, an experienced attorney in the Judge Advocate General Corps understood exactly what the General expected of him. The ten accused requested that Captain Walter Parsons who had commanded them on the Highway be assigned to defend them. Parsons, an engineer, not an attorney went into the court martial with three days of preparation and no idea of its true purpose. He thought the trial concerned guilt, innocence, and justice.

Parsons managed to get one man acquitted. Willie Calhoun had, with permission, gone to personnel to settle an allotment and wasn’t even in the area when the “crime” occurred. The court convicted the others, sentenced them to serve at hard labor. Heard (who had been the sergeant in charge) for twenty years, Bridges for eighteen years, Ratliff for twelve years. Rucker and Howell had at least moved toward the truck, they got five years. Hollingsworth, Weaver, Lindsey and Fulks had actually climbed on to the truck. They got three years.

The system required that the Staff Judge Advocate review the outcome of the trial. At the end of July, he issued his decision. He reversed the convictions of Lindsey, Hollingsworth, Weaver and Fulks and returned them to duty. MP’s took the remaining five back down the road they had just helped build, back into the lower 48 to a stockade/rehabilitation center in Battle Creek, Michigan. The Army, needing soldiers more than prisoners, put men convicted of non-violent crimes in rehabilitation centers. In those prisons the guards “retrained” them and ultimately if they judged the prisoner sufficiently retrained they returned him to active duty. The system released the five “mutineers” in June 1944.

After the war most of the ten all but disappeared from the historical record. Willie Calhoun, who had been acquitted, received a medical discharge in 1944. He returned to Georgia, got married, raised three kids and then in 1974, for unknown reasons, a neighbor shot and killed him.

Eugene Fulks made it home to Vicksburg, Mississippi in 1945 and got married. In 1946 his wife stabbed him to death.

Warren Lindsey returned to his home in Wilson County, North Carolina. He married, raised three daughters and made a living as an autobody repairman. He died at 80 in 2001.

Josh Weaver moved to Savannah, Georgia and worked for a steel product manufacturing company until his retirement in 1986.

James Hollingsworth lived out his life as a bachelor in Milledgeville, Georgia before passing away at 81 in 1994.

Robert Rucker returned to Rowan County, North Carolina. He married and raised three sons and two daughters. Robert died tragically in an auto accident in 1972.

Willie Howell returned to Madison County, Georgia. He married, raised five kids, and passed away at 84 in 2003.

Lee Ratliffe returned to Stanly County, North Carolina. He married and the couple had four children when Lee’s wife left him for someone else. He worked at a highly skilled job for Young Manufacturing, raised the kids by himself and lived to 77.

James Heard simply disappeared from the record. Shortly after the war his mother and two of his brothers joined the “Great Migration” and settled in the Washington, D.C. area. It is likely that James joined them there.

Finally, Sims Bridges. Back on active duty in France he assaulted a female civilian. His conviction was reinstated and he served his time at the United States Penitentiary in Terre Haute. Released, he moved to New York, but robberies landed him in the state prison in Attica, not once but twice. Released on parole in 1981, Sims disappeared from the historical record.

These men, along with hundreds of other African American soldiers, survived horrific conditions to build military roads including the Alcan Highway to make Alaska Territory defensible by the U.S. Army. That same Army refused to protect ten of them and instead meted out harsh and unfair discipline for their refusal to ride in the unheated back of a truck in sub-zero temperatures, a journey that surely would have killed them.