Onesimus was an enslaved African, credited with bringing a traditional African practice to Boston, Massachusetts that resulted in a smallpox inoculation process. The first Africans arrived in Massachusetts in 1638 and by 1700, the city of Boston included approximately one thousand enslaved men, women, and children in a total population of 6,700. Smallpox was one of the colony’s deadliest diseases, often entering on slave ships. Onesimus’s name at birth is unknown, as well as his age, as neither were recorded at his time of capture. Because of his language, he was probably from the Akan ethnic group in what is now Ghana. It is known that he was first taken from the Windward & Rice Coast, on the ship Bance Ifland (island), arriving in Boston, Massachusetts, on May 6, 1704.

In 1706, he was gifted by the congregation of North Church, to their Puritan Minister, Cotton Mather. Mather named the man Onesimus after a first century AD slave mentioned in the Bible. Mather saw a particular intelligence in Onesimus that he regarded as “exceptional among his peers” and instructed Onesimus in reading and writing, so that he would be a proper representative of the Mather family and home.

Around 1716, Mather asked Onesimus if he had ever had smallpox and he answered both yes and no. Onesimus described a process, practiced in his native land that involved rubbing the pus from the infected person into an open wound on the arm of a non-infected person. Onesimus stated that whomever had the courage to go through the process, was forever free of the disease.

This process—known as variolation at the time—was long practiced among sub-Saharan Africans. Mather was fascinated and verified Onesimus’ story by speaking with other enslaved Africans that described going through the same process in their native lands. Mather then wrote a letter to the Royal Society of London, in hopes of promoting the procedure, but was immediately rejected. The procedure was distrusted by those suspicious of African medicine and some saw it as an attempt to poison white residents of Boston. Mather’s idea was ridiculed by local newspapers and the Puritan minister was vilified.

Onesimus was allowed by Mather to earn independent wages, have his own home and family which eventually included a wife and two children both of whom died before they were ten. After the deaths of Onesimus’s children, Mather attempted to convert him to Christianity, but Onesimus refused, which brought embarrassment on the Mather home because of his status as the leading minister in Boston. Onesimus attempted to purchase his freedom by offering monies for another slave named Obadiah to take his place and Mather subsequently gave Onesimus partial freedom.

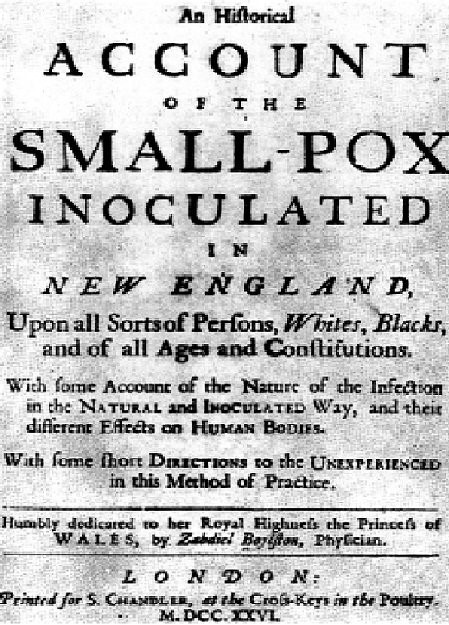

In 1721, Boston experienced a smallpox outbreak. Local physician, Dr. Zabdiel Boylston, uncle of founding father John Adams, took interest in Mather’s procedure and agreed to perform it on his patients. Dr. Boylston administered the procedure to 242 patients. Only 6 of his patients died. From that point Onesimus’s method became the standard way to treat smallpox patients.

Seventy-five years later, in 1796, Edward Jenner used Onesimus’s concept to developed a vaccine for smallpox which would be widely used for the next two hundred years. In 1980, the World Health Organization declared smallpox completely eradicated, the only infectious disease to have been entirely wiped out.