The National Association of the Advancement of Colored People’s (NAACP) Silent Protest Parade, also known as the Silent March, took place on 5th Avenue in New York City, New York on Saturday, July 28, 1917. This protest was a response to violence against African Americans, including the race riots, lynching, and outrages in Texas, Tennessee, Illinois, and other states.

One incident, in particular, the East St. Louis Race Riot, also called the East St. Louis Massacre, was a major catalyst of the silent parade. This horrific event drove close to six thousand Blacks from their own burning homes and left several hundred dead.

James Weldon Johnson, the second vice president of the NAACP, brought civil rights leaders together at St. Phillips Church in New York to plan protest strategies. None of the group wanted a mass protest, yet all agreed that a silent protest through the streets of the city could spark racial reform and an end to the violence. Johnson remembered the idea of a silent protest from A NAACP Conference in 1916 when Oswald Garrison Villard suggested it. All the organizations agreed that this parade needed to be composed of Black citizens, rather than a racially-mixed gathering. They argued that as the principal victims of the violence, African Americans had a special responsibility to participate in this, the first major public protest of racial violence in U.S. history.

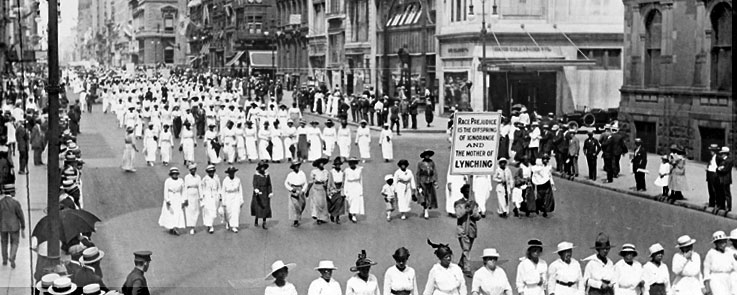

The parade went south down 5th Avenue, moved to 57th Street, and then to Madison Square. It brought out nearly ten thousand Black women, men, and children, who all marched in silence. Johnson urged that the only sound to be heard would be “the sound of muffled drums.” Children, dressed in white, led the protest and were followed by women, also dressed in white. Men brought up the rear, dressed in dark suits.

The marchers carried banners and posters stating their reasons for the march. Both participants and onlookers remarked that this protest was unlike any other seen in the city and the nation. There were no chants, no songs, just silence. As those participating in the parade continued down the streets of New York, Black Boy Scouts handed out flyers to those watching that described the NAACP’s struggle against segregation, lynching, and discrimination, as well as other forms of racist oppression.

James Weldon Johnson wrote in his 1938 autobiography Along This Way that “the streets of New York have witnessed many strange sites, but I judge, never one stranger than this; among the watchers were those with tears in their eyes.”