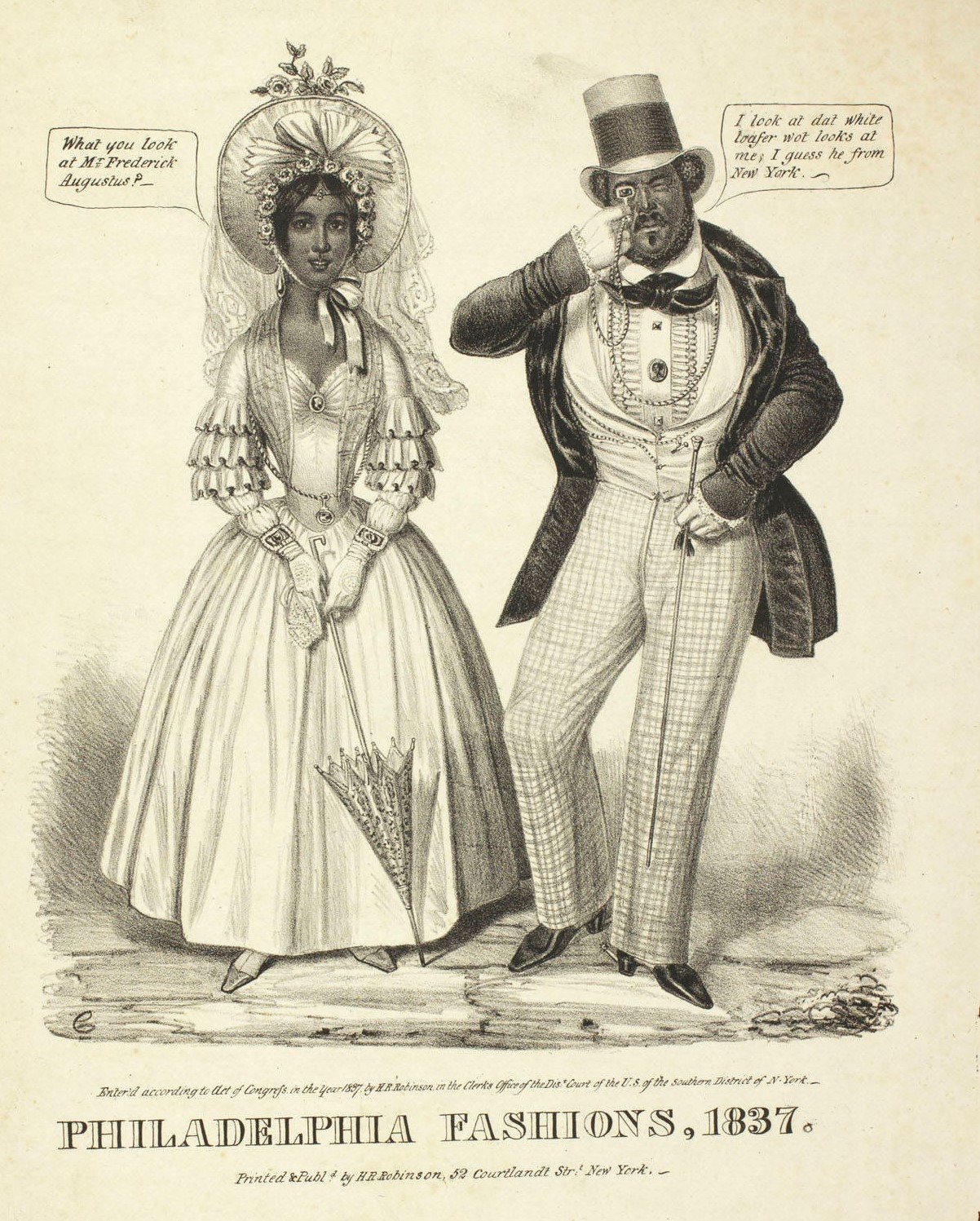

Frederick Augustus Hinton, barber, abolitionist, early advocate for independent Black presses, and founding member of the Colored Conventions movement, was born enslaved in Raleigh, North Carolina, to unknown parents. Emancipated in Philadelphia in 1825 at the age of twenty-one, Hinton quickly became a member of the city’s elite society of African American political activists. Within two years he had opened his “Gentleman’s Dressing Room” on South 4th Street where he operated a prosperous hairdressing, wig-making, and perfume business. In 1828 he married Eliza Howell, the daughter of wealthy oysterman and community leader, Richard Howell, also originally from North Carolina. In 1829, Hinton joined St. Thomas African Episcopal Church where he networked with other influential Black families such as the Fortens, Purvises, Burrs, and Casseys.

Hinton embraced all aspects of African American organizing in the 1830s and 1840s. He sat on committees to promote the abolitionist newspapers, the Rights of All (1829-30) and the Colored American (1837-41) and served as the Philadelphia distribution agent for William Lloyd Garrison’s Liberator. He was a founding member of the Philadelphia Library Company of Colored Persons. In December 1833, along with Joseph Cassey, Robert Purvis, Jacob C. White, William Whipper, Thomas Butler, James McCrummell, and John D. Dupee, he delivered “Eulogy on William Wilberforce, Esq.” in the Second African Presbyterian Church.

Hinton was also a promoter of national Colored Conventions where African Americans from numerous states came together to discuss the problems and prospects for the race. He served as a delegate to five out of the first six national Colored Conventions, 1830-1835, including the first in 1830 led by Bishop Richard Allen to discuss the question of immigration to Canada as an alternative to the persecution experienced by northern Blacks. Hinton, like many free Blacks in the North, opposed the American Colonization Society’s efforts to relocate African Americans to Africa, which he saw as a ploy to strengthen slavery in the United States.

In the late 1830s, however, discouraged by the 1837 disfranchisement of Black Philadelphians and more generally by the discrimination they faced, Hinton broke away from anti-colonizationists to promote immigration to Trinidad and Liberia. In 1838 he joined with Robert Purvis in the drafting of the Appeal of Forty Thousand Citizens, which defended the accomplishments of Philadelphia’s people of color and called on white voters to reject the new constitution that would deny suffrage to free Blacks.

Hinton contributed to the establishment of the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society in 1836 and served as a delegate to several of its conventions. A longtime friend of William Lloyd Garrison and other white reformers, Hinton became discouraged by infighting and lack of progress in Garrisonian abolitionism and publicly denounced Garrison in the 1840s. Hinton also had a brief falling out with abolitionists Robert Purvis and William Whipper over the language and policies of the American Moral Reform Society, which he had helped to found.

Two years after his wife Eliza and infant daughter died in 1835, Hinton married Georgia-born Elizabeth S. Willson (1814-1871). Elizabeth’s brother, Joseph Willson, had been Hinton’s protégé and wrote Sketches of the Higher Classes of Colored Society in Philadelphia (1841). Frederick A. Hinton’s only surviving child from his first marriage, artist and educator Ada Howell Hinton (1832-1903), had established her own school by 1849. That year, Frederick A. Hinton died in the 1849 cholera epidemic at the age of 45.