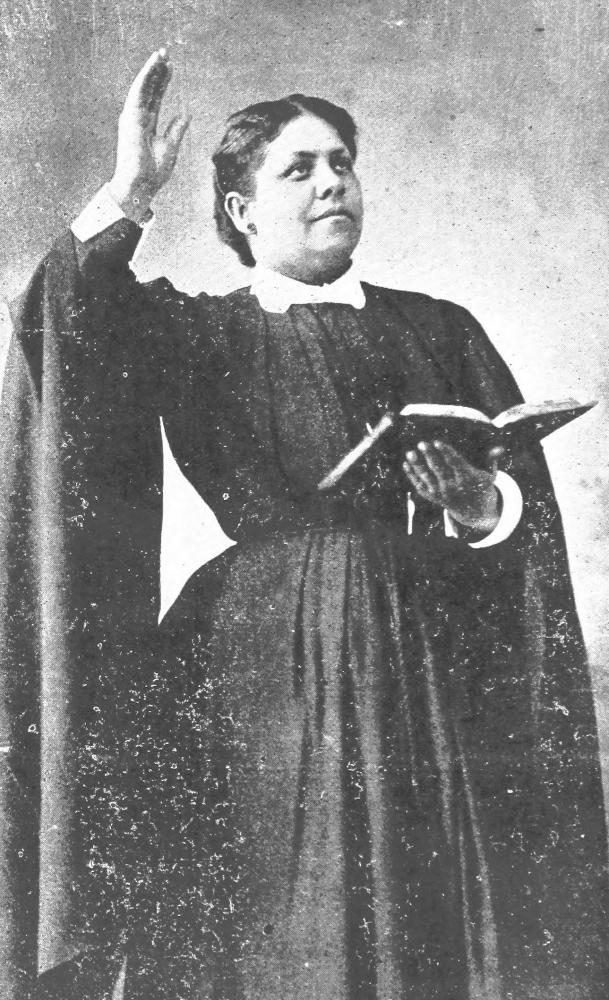

Annie E. Brown gained fame as a Methodist Episcopal evangelist in the late 1800s and early 1900s, earning a national reputation among blacks and whites alike with her missionary work. While most of Brown’s work was done along the Atlantic seaboard, she traveled as far west as Denver, Colorado and her ministry gained a great deal of publicity in both white and black newspapers.

Brown was born in 1862 and grew up in Washington, D.C. She was married at the age of 15 to Henry F. Brown, an employee of the federal government. Three of Brown’s children survived to adulthood. Two of her sons went into the professions, becoming a doctor and a lawyer at a time when it was difficult for African Americans to break into those fields.

In her ministry, Brown conducted revivals in association with local churches. She was especially famous for street preaching and her use of a “Gospel Wagon” to spread her message throughout the country. The wagon seated fifteen people, included an organ, cooking facilities and utensils and a speaking platform. The wagon also prominently displayed religious inscriptions.

Brown’s role as a female preacher was notable given the social role of women in early twentieth century America. One constant feature of her work was the meetings that she held for men only. Brown often used these occasions to criticize husbands for their treatment of their wives. Brown was also well known for her lecture, “Should Women Preach?” where she incorporated references to scripture and her interpretations of ancient customs.

Brown’s popularity may have been helped by the fact that her message reflected the accommodationism that was preached and popularized by Booker T. Washington. She urged African Americans not to see whites as their enemies. In her sermons, Brown counseled black people to de-emphasize politics, saying they had had no place in religion. Brown stressed the importance of black people keeping their connection to the South. Somewhat contradictorily, in her sermons Brown cited black politicians who served as federal appointees as the best example of successful black men and proof that African Americans could succeed by staying in the South.

Brown branched out from the ministry to other endeavors. She engaged in social reform work, assisting other African American women in establishing the Light House Rescue Mission for troubled young women in New York City, New York. The goal of the mission was to provide housing and work opportunities for young women by giving them vocational education. Brown also funded and launched a similar enterprise in Florida. These institutions were clearly influenced by the philosophy of Booker T. Washington. In a statement written by Brown and the school’s trustees they declared, “The Negro must learn that work with the hand is the first duty of man. Thus we combine heart-culture and hand-culture, book-learning with work; salvation with industry.”

Annie E. Brown died on February 8, 1918 at the home of her son, Dr. Harry Brown in Baltimore, Maryland. Three sons survived her. Her granddaughter, Anne Brown, became a famous Juilliard-trained opera singer who collaborated with George Gershwin and then was the first woman to perform as Bess in Porgy and Bess.