Freedom Summer (June-August, 1964) was a nonviolent effort by civil rights activists to integrate Mississippi’s segregated political system. It began late in 1963 when the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) decided to recruit several hundred northern college students, mostly white, to work in Mississippi during the summer. They helped African American residents try to register to vote, establish a new political party, and learn about history and politics in newly-formed Freedom Schools.

Because black Mississippians were barred from Democratic Party primaries and caucuses, they challenged the right of the party’s all-white delegation to represent the state at the Democratic National Convention (DNC) in August in Atlantic City, New Jersey. Ineligible to vote in the Democratic Party primaries in what was a one-party state effectively meant they were barred from participating in politics.

In response, they held a parallel “Freedom Election” in November and challenged the right of the all-white Mississippi congressional delegation to represent the state in Washington, D.C. More than sixty thousand black Mississippi residents risked their lives to attend local meetings, choose candidates, and vote in the “Freedom Election” that ran parallel to the regular 1964 national elections. Several hundred African-American families also hosted northern volunteers in their homes.

Nearly one thousand five hundred volunteers worked in project offices scattered across Mississippi. They were directed by 122 SNCC and CORE paid staff working alongside them or at headquarters in Jackson and Greenwood. Most volunteers were white students from northern colleges, but 254 were clergy sponsored by the National Council of Churches, 169 were attorneys recruited by the National Lawyers Guild and the Lawyers Constitutional Defense Committee, and 50 were medical professionals from the Medical Committee for Human Rights.

Some key figures that participated in Freedom Summer included Robert Moses, who proposed the idea of Freedom Summer to SNCC and COFO leaders in the fall of 1963 and was chosen to direct it early in 1964. Another was Dave Dennis who was a veteran of earlier sit-ins and freedom rides; he was the leader of CORE’s operations in Mississippi and Louisiana and assistant director of COFO (Council of Federated Organizations). Julian Bond and Mary King ran the SNCC Communications Section, making sure that the national media was available to cover events and that project staff stayed informed and in touch about the constant dangers.

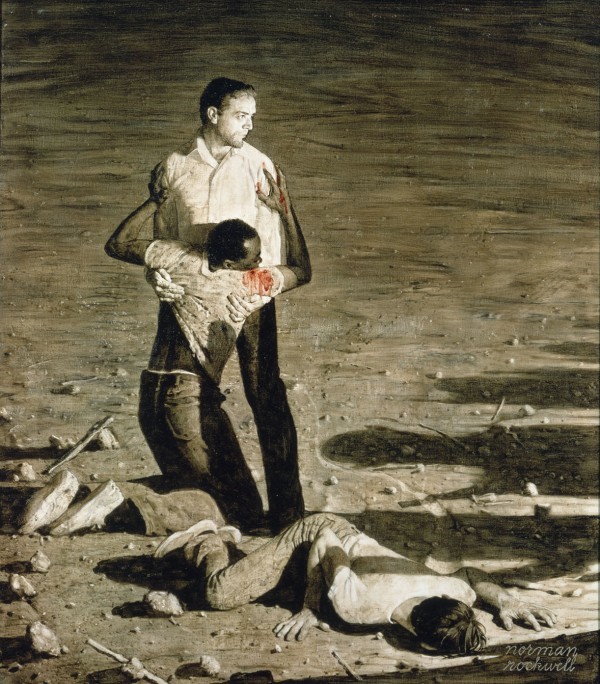

Those who opposed this movement were mainly Mississippi’s elected officials, who at all levels denounced the Summer Project. The state’s senators and governor publicly refused to obey federal integration laws, the state police nearly doubled in size, legislators passed new laws prohibiting picketing and leafleting, and local sheriffs and police chiefs expanded their forces and acquired new weapons. Business leaders banded together in white Citizens Councils to coordinate punishment of African-Americans who participated in Freedom Summer. They foreclosed mortgages on black residents’ homes, fired workers from jobs, banned customers from shopping in stores, and shut down food pantries for the poor. And white supremacy groups such as the Ku Klux Klan inflicted violence on black residents and civil rights workers. Between June 16 and September 30, 1964, there were at least six murders, including James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner, who were killed on June 21 near Philadelphia, Mississippi. There were also twenty-nine shootings, fifty bombings, more than sixty beatings, and over four hundred arrests of project workers and local residents.

Residents and volunteers were met by extraordinary violence, including murders, bombings, kidnappings, and torture. Much of this was covered on national television and focused the country’s attention on civil rights issues for the first time. Public outrage helped spur the U.S. Congress to pass the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. “Freedom Summer” is a term invented after these events occurred. At the time, participants usually called it the Mississippi Summer Project.