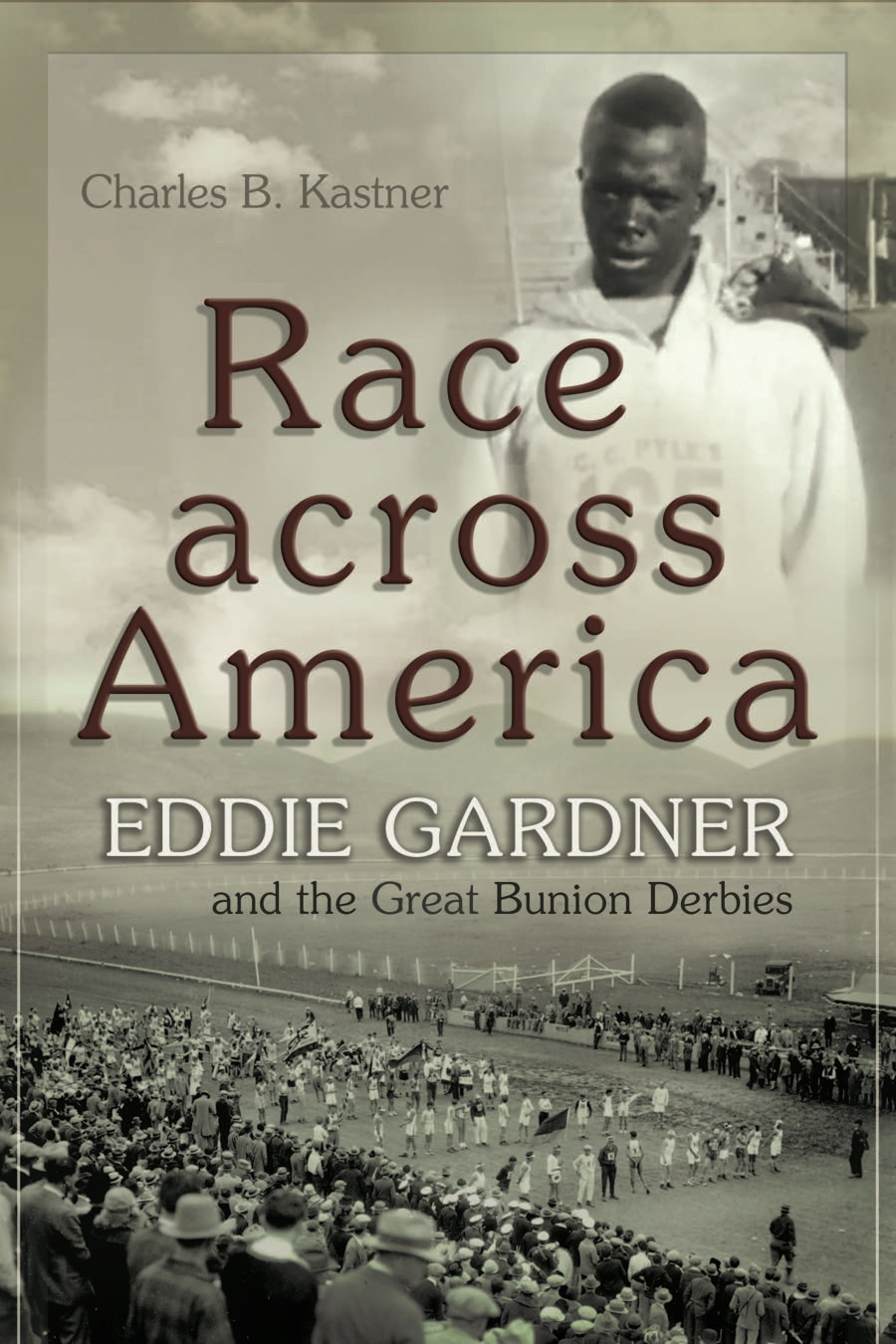

In this article below historian Charles B. Kastner describes his new book, Race Across America, on Eddie Gardner, the now virtually unknown marathon runner who achieved nation fame in his footraces across the United States in the 1920s.

Race across America: Eddie Gardner and the Great Bunion Derbies, is my third and last book about two trans-America footraces that crossed the country in 1928 and 1929. They were nicknamed “bunion derbies” by the press. This book focuses on the African American runner Eddie “the Sheik” Gardner, as he was known to his legions of fans in Seattle, where he lived and competed in the 1920s. He had gained local fame as the record-setting three-time winner of the annual Washington State Ten-Mile Championship. When he entered the first trans-America race in 1928, this black “bunioneer” risked his life to compete against white runners when the Los Angeles to New York race took the runners through Texas, Oklahoma, and Missouri, where by law or custom black were not supposed to compete against whites in sporting events.

My introduction to the bunion derbies began with tragedy. In November 1998, my father-in-law lay dying in a hospital bed. As we were talking, he told me about a footrace he remembered from his childhood that started in Port Townsend and finished in Port Angeles, Washington. I knew that the race distance had to be about fifty miles. At first, his statement seemed hard to believe: I had no idea that people were competing at the ultramarathon distances so long ago. I thought ultramarathoning was an offshoot of the running boom of the 1980s when masses of Americans took up the marathon challenge and began crowding, until then, mostly small local events.

Several months after his death, I traveled from my home in Seattle to Port Angeles and began scrolling through rolls of microfiche to see if I could uncover any information about the race. This was before the days of digitized newspapers. I was on a mission of discovery. Finally, in the roll marked “June 1929,” I found articles in the Port Angeles Evening News about what was billed as the “Great Port Townsend to Port Angeles Bunion Derby.” My first reaction was “What is a Bunion Derby?” And my second was “Why would a bunch of ‘average Joes’—lumberjacks, farmers, postmen, and laborers—attempt such a thing?” Of the twenty-two men who started, eleven men finished the event. They had little training and little understanding of what they had gotten themselves into. Most crossed the finish line with blisters the size of half dollars, shoes oozing blood, and legs so sore and cramped that one finisher had to crawl across the finish line–all this for small cash prizes that ranged from $100 for first to $10 for tenth.

One article noted that local officials had dreamed up the event after the famous sports agent Charles C. Pyle held his first-of-its-kind trans-America “Bunion Derby” in the spring of 1928. The article also mentioned that a Seattle runner, Eddie “the Sheik” Gardner, had competed in the event. That information piqued my interest.

I then went to the main branch of the Seattle Public Library, pulled rolls of microfilm from the newspaper file and began scanning through the sports pages of the Seattle Post- Intelligencer and the Seattle Times. I quickly found article after article about the event starting in late February 1928.

I then realized that Seattle’s entry, Eddie Gardner, was black. That came as a shock to me. I was under the impression that few if any African Americans competed in ultramarathon events. Then I wondered about the challenges a black runner would face running in an integrated footrace, especially when the 1928 race took the derby through Texas, Oklahoma, and Missouri.

The bunion derby was relatively easy to follow. It started in Los Angeles on March 4, 1928, and finished in Madison Square Garden on May 26, 1928, after 84 days and 3,400 miles of daily ultramarathon racing. Each day’s race or “stage run” stopped at a given city or town for the night. The next morning, the men gathered at the prior day’s finish line until a starter’s gun sent them off to the next designated town down the road.

After each stage run, a cadre of nationally syndicated reporters that accompanied the event filed stories about that day’s race. Combine these syndicated stories with local reporting and I could piece together a detailed account of the race. This involved many hours of research to determine what newspapers still survived from a given town, ordering the microfilm through inter-library loan, and then reading through rolls of microfilm and copying any pertinent articles I found.

After I had read through more than seventy-five different newspapers, four first-hand accounts of the races, and a scattering of secondary accounts of the event, Eddie Gardner emerged as a gifted but erratic runner in the 1928 derby, a man who had the most first-place finishes in the daily races, seventeen wins, but still managed to finish only in eighth place. In all the articles I read, only one local newspaper, Missouri’s Springfield Daily News, noted that whites had been “especially [unpleasant] to the Negro runners” in Missouri.

Then I turned to the black press. From stories written in such newspapers as Oklahoma’s Black Dispatch, The Chicago Defender, the Pittsburgh Courier, the California Eagle, and Seattle’s Northwest Enterprise, I quickly realized that there was an untold story about the bunion derby that the white press ignored. As one of the top runners in the race, Eddie Gardner endured a firestorm of death threats and intimidation from white spectators, especially in the Panhandle of Texas and in western Oklahoma, where one white farmer reportedly rode behind him with a gun trained on his back daring him to pass a white man. George Curtis, Gardner’s black trainer, came in for similar abuse as he followed behind Eddie in his car along the course. In McLean, Texas, a group of white townsmen surrounded his car and threatened to burn it for helping Eddie stay in the derby.

Gardner’s gutsy challenge to Jim Crow became a source of pride for Black America, and his exploits were widely reported in the black press. Along the course, African Americans often took in the black runners, fed them, and gave them a safe place to sleep for the night. When the derby reached Chicago, many of its black citizens lined the road starting fourteen miles west of the city to greet them.

As an avid long-distance runner, I simply could not fathom what Eddie had endured. I would train for months to run one marathon. I had high-tech shoes, sports drinks and gels, ample water supplies along the course, and a cadre of well-wishers who shouted encouragement to me from the sidelines. During the race, I often hit the proverbial “wall” after staying on my feet for twenty miles and stumbled across the finish line, leg dead, exhausted, and vowing never to attempt a marathon again. Then I thought of Gardner: he ran about forty miles a day for eighty-four consecutive days with none of the hi-tech gear I had, and in three states he had to do so while his tormentors yelled death threats and racial slurs at him. And he was fast, eye-poppingly fast, with the legs to run at three-hour marathon pace at any distance under thirty miles.

Then Eddie did something even more courageous. The next year, Pyle reversed course and started the derby in New York City and finished in Los Angeles. Gardner had trained hard for the second race and led a field of elite trans-America runners down the Eastern Seaboard to Baltimore and then west across the Appalachian Mountains. When he crossed into Missouri, he did so after sewing an American flag on his running jersey, announcing to all who saw him that he had returned to Jim Crow as an American and on that day the greatest ultramarathoner in the world.

In writing this book, I undertook a crash course in African American history. I knew Gardner graduated from Tuskegee Institute in 1918 so I turned first to its founder, Booker T. Washington, and his book Up from Slavery. Washington did not advocate challenging southern segregation directly but hoped to convince southern whites through the craftsmanship and diligence of his graduates that blacks were worthy of citizenship rights denied to them after whites regained control of southern statehouses after the fall of Reconstruction. Full equality for blacks would come, he wrote, “through no process of artificial forcing but through the natural law of evolution.”

Gardner did not have the luxury of time. If he wanted to compete as an elite athlete in the new sport of trans-America racing, he had to risk life and limb to do so. Then I read W. E. B. Du Bois’s book The Souls of Black Folks, his 1903 call for resistance against the new order in the “redeemed South,” and I began to understand where the ideological underpinnings of Gardner’s response came from.

My final challenge was fleshing out the lives of Eddie Gardner and the two other black finishers: “Smiling” Sammy Robinson, from Atlantic City, New Jersey, a thirty-four-year-old boxer and war veteran; and Tobie Joseph Cotton Junior, a 15-year-old high school freshman from California, who entered the race in what seemed a crazy attempt to win the $25,000 in prize money to save his struggling family from poverty. For Gardner, I took a trip to Tuskegee University and spent a week searching through its archives. There I found his college transcripts and school catalogs from Eddie’s school days, which were a great aid in my research. For Robinson, the staff at Atlantic City’s public library was a huge help in locating newspaper articles about him. My big break for Tobie came when I found a copy of his father’s long-forgotten and out-of-print account of his son’s race across America, titled How He Ran Across the Continent to Help an Invalid Father. These resources, combined with primary sources such as census data and death certificates, allowed me to reconstruct the lives of these forgotten men.

The result is a book that documents the first integrated sporting event to cross the country. It gives some long-overdue recognition to Eddie Gardner, America’s first great black ultramarathoner and a courageous and unsung hero in the long struggle against segregation in this country.