In the following article Wyoming historian Brigida R. Blasi explores the history of now nearly forgotten Dana, a small predominately black coal mining town about 150 miles west of Cheyenne. Here is her account.

The town of Dana has largely been forgotten in the history of Wyoming and the West, gone from living memory and barely receiving a mention in accounts of the long and varied history of the state’s boom and bust coal mining towns. The Union Pacific Railway section called Dana, which started out as a stage stop along the Overland route, spent most of its existence as quick place to stop for water or rest along the transcontinental railroad, the Union Pacific Railway, about 150 miles west of Cheyenne, the Territorial and later State Capital. Dana’s principal but largely forgotten story, however, peaks with a short but noteworthy burst of historical activity between 1888 and 1891 when it became a Union Pacific Coal Company (UPCC) mining town.

Although its importance has been either ignored or obscured, Dana is highly significant to the history of Black Wyomingites and to the early struggle for workers’ rights in the West. It represents the first documented occurrence of the UPCC expressly recruiting a group of Black men to work in the Wyoming coal mines. It was furthermore the first and only Wyoming coal town where Blacks made up the ethnic majority. In the few short years the nearby Dana mine was active, its population of Black miners also inadvertently brought widespread attention to a major issue of fair labor practices through their demand for equity and honesty in their work and pay.

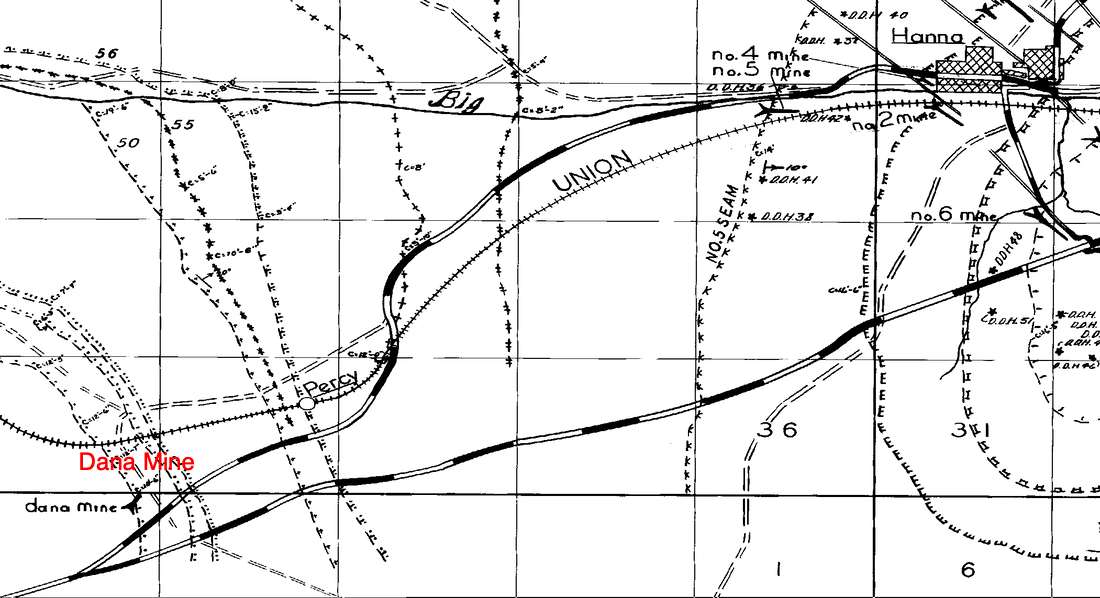

Dana was one of several short-lived coal camps in southern Wyoming. The Dana mine first opened in winter 1888 with workers from the nearby coal town of Carbon sent in build the mine entrance and set up the processing equipment. By January 1889, U.P. Railway surveyors were plotting out a course for the spur to the Dana mine. Despite glowing predictions for the quality and quantity from official histories, newspaper reports, and even some government reports, it appears the UPCC was aware of the poor quality and relative lack of merchantable coal at Dana. The Panic of 1884 had caused a slump in the coal market, fuel for the formation of the first true labor union in the western mines, the Knights of Labor, and the first major miners strikes. After the economy recovered, the UPCC compensated for these short-term losses by mining every seam that appeared even nominally viable. Dana was one town whose prosperity seemed fated to quickly wane. The Carbon men sent to open up the mine quickly proved too few and UPCC agents set to work recruiting more workers as they decided to move ahead with formation of this new coal town.

Image Courtesy: Central Washington University Libraries, Fair use image

By the time newspapers reported that a walkout had halted work at Dana in December 1889, the UPCC had already sent a specially chosen agent, James E. Shepperson, to recruit replacement Black miners. At the time, miners were paid by the tonnage they dug. The company was weighing their coal after screening it and thereby significantly diminishing their pay. Miners demanded a raise in pay per ton and when they were refused, they went on strike. Instead of complying with worker demands, the UPCC engaged Shepperson to replicate the success he had recruiting Black strikebreakers to Washington Territory. Enticed by the promise of opportunity in the western coal mines and unaware they were being recruited as strikebreakers, about 200 Black miners and their families followed Shepperson to Dana in early February 1890.

Just weeks after the Black miners arrived, Wyoming legislator Thomas Sneddon proposed House Bill 18 (HB 18) to the Territorial Legislature. The measure would allow the Territory to regulate the weighing of coal. He used Dana’s Black miners’ refusal to accept the weighing method to underscore his argument that miners were being treated especially unfairly. He argued before fellow legislators, “When the company proposed this method at Dana the [white] miners would not consent to it, and the company sent east for negroes and now the negroes would not even do it.” Tensions ran high in the coal mines at the time with an impending strike in Rock Springs. Local newspaper articles conveyed fear of the unrest spreading by reminding its readers of other strikes across the country and the 1885 Chinese Massacre in which at least 28 Chinese workers were killed. After much debate, the bill passed in March. This was a major legislative victory for laborers in the territory’s largest industry and the debate coverage brought to light unflattering practices by the company and bosses.

The UPCC, via the media, used Dana’s Black miners and recruiter James E. Shepperson as scapegoats to try to avoid bad press. Shepperson received the brunt of the blame but escaped back to Washington. Though his role in Dana was forgotten, his work in Washington guaranteed that he would be recognized as one of the most significant advocates for Black miners in the West.

Some of Dana’s Black miners left when they realized the company intended them to work as strikebreakers and was refusing them a fair wage. Those who stayed made history once again by being the first of only two examples in Wyoming’s history of a town with a Black majority. The other was the homesteading town of Empire. Many of those who stayed in Dana put down deep roots and when the mine shut down just a few years later, they were transferred to other area mines. Many were transferred to the No. 1 mine in the nearby UPCC town of Hanna where some of them suffered in two major mine disasters there in 1903 and 1908. The 1903 explosion at Hanna was Wyoming’s deadliest mine disaster and killed approximately 50 Black miners out of 169 total fatalities. Others were transferred to Rock Springs. Those who did stay arrived in Wyoming just in time to be counted among the first residents of the State of Wyoming when the territory was awarded statehood in July 1890.

Until recently, it was possible to find just a few written accounts of Dana’s history. Usually, this included information on the Lincoln Highway or references to train robberies. Dana’s significant Black history was completely negated due to the UPCC’s efforts to erase the story because it reflected poorly on them. The official company history, History of the Union Pacific Coal Mines 1868-1940, included the only significant history of Dana for more than 130 years after its founding. Though the town of Dana was given its own chapter, the Black miners, conversely, received only a few dismissive and misleading sentences: “the Railroad imported a number of experienced negro mine workers from the South. Almost at once it became apparent that the rigorous weather would be too severe for the Southerners, and there was a large turnover of negro labor.” Dana’s fleeting existence contributed to the ease with which the town’s early Black inhabitants were misrepresented and this dismissal was repeated in other publications. Only recently has the full story of Dana’s miners come to light and with it an important chapter in Wyoming’s lost Black history.