Langston, Oklahoma is one of the few remaining all-black towns located in the former Oklahoma Territory. The town, which opened for settlement on October 22, 1890, was named for John Mercer Langston, who took office as the first black Virginian to serve in the United States House of Representatives only one month earlier.

Langston’s principal founders were William L. Eagleson, a prominent newspaper editor, Edward P. McCabe, a former Kansas state auditor, and Charles W. Robbins, a white land speculator. Eagleson and McCabe had both been ardent supporters of black migration to Oklahoma Territory and through their efforts the town’s population was settled by blacks from Kansas and several Southern states.

Taking on the role of chief promoter of Langston, McCabe encouraged only those blacks with sufficient resources to support themselves to move to the town. Through his efforts the town attracted an estimated 600 settlers by January 1891 with more blacks settling in the surrounding rural areas.

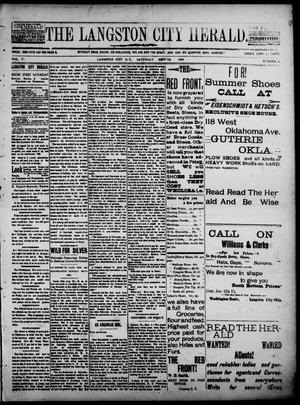

Many small businesses opened to support this burgeoning population. Among those first established were several grocery stores, saloons, blacksmith shops, barbershops, a feed store, and a newspaper, the Langston City Herald, edited by McCabe. Within two years, at least twenty-five businesses, from banks to ice cream parlors, were operating in town.

There were also several churches, Masonic orders, public and private elementary and secondary schools, a volunteer fire company, and a seventy-five member militia. Although Langston’s citizens made a tremendous effort to attract a railroad company to build through their town, they were ultimately unsuccessful in this endeavor. The absence of convenient access to the rails dealt the town an economic blow and stunted its population growth potential.

In spite of the railroad setback, however, townspeople successfully lobbied to have the Colored Agricultural and Normal University of Oklahoma (today Langston University) established in Langston in 1897. The presence of this institution, the only publicly operated institution dedicated to the higher education of African Americans in Oklahoma, has contributed to Langston’s survival even as other small towns in Oklahoma, both black and white, have collapsed as a result of economic depressions, urbanization trends, and war time migrations. In 2008, Langston’s population, including university students, was 1,712, currently marking it as the largest of Oklahoma’s historically black towns.