One of the last of the major riots of the “Red Summer” of 1919, the so-called race riot in Elaine, Arkansas was in fact a racial massacre. Though exact numbers are unknown, it is estimated that over 200 African Americans were killed, along with five whites, during the white hysteria of a pending insurrection of black sharecroppers. The violence, terror, and concerted effort to drive African Americans out of Phillips County, Arkansas was so jarring that Ida B. Wells, a founder of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), published a short book on the riot in 1920. It was also widely reported in African American newspapers like the Chicago Defender and generated several public campaigns to address the fallout.

On the night of September 30, 1919, approximately 100 African Americans, mostly sharecroppers on the plantations of white landowners, attended a meeting of the Progressive Farmers and Household Union of America at a church in Hoop Spur, a small community in Phillips County, Arkansas. They hoped to organize to obtain better payments for their cotton crops. Aware of white fears of Communist influence on blacks, the union posted armed guards around the church to prevent disruption and infiltration.

During the meeting, three white men pulled up to the front of the church. One of the men asked the guards, “Going coon hunting, boys?” Gunfire erupted after the guards made no response. Though sharp debate exists as to who fired first, the guards killed W.A. Adkins, a security officer from the Missouri-Pacific Railroad, and injured Charles Pratt, the deputy sheriff.

The next morning, an all-white posse went to arrest the suspects. Though they encountered little opposition from the black community, the fact that blacks outnumbered whites ten-to-one in this area of Arkansas resulted in great fear of an “insurrection.” The concerned whites formed a mob numbering up to 1,000 armed men, many of whom came from the surrounding counties and as far away as Mississippi and Tennessee. Upon reaching Elaine, the mob began killing blacks and ransacking their homes. As word of the attack spread throughout the African American community, some black residents fled while others armed themselves in defense. The mob then turned its attention to disarming those blacks who fought back.

Meanwhile, local white newspapers further inflamed tensions by reporting that there were planned black uprisings. By October 2, U.S. Army troops arrived in Elaine, and the white mobs began to disperse. Federal troops rounded up and placed several hundred blacks in temporary stockades, where there were reports of torture. The men were not released until their white employers vouched for them. There was also considerable evidence that many of the soldiers sent to quell the violence engaged in the systematic killing of black residents.

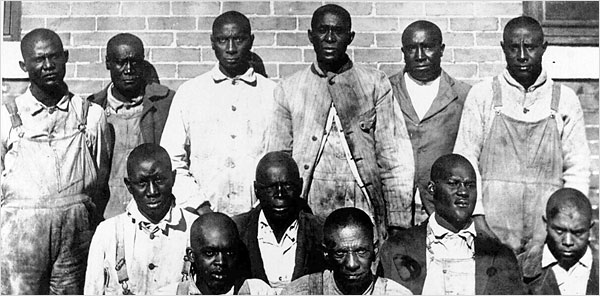

In the end, 122 blacks but no whites were charged by the Phillips County grand jury for crimes related to the riots. Their court-appointed lawyers did little in their defense despite the investigation and involvement of the NAACP. The first 12 men tried for first-degree murder were convicted and sentenced to death. As a result, 65 others entered plea bargains and accepted up to 21 years for second-degree murder. Led by black attorney Scipio Africanus Jones, the NAACP and other civil rights groups worked towards retrials and release of the “Elaine Twelve.” Eventually they won their release, with the last of the twelve set free on January 14, 1925.