In 1963, prominent Seattle, Washington civil rights leaders united to form the Central Area Civil Rights Committee (CACRC). Members were typically notable figures in other existing groups like the Urban League (Edwin Pratt), CORE (Walter Hundley), and the NAACP (Charles Johnson), although some represented community churches (John H. Adams, Samuel McKinney). Together the coalition professed to be the predominant, unified voice on local civil rights issues. For nearly five years, CACRC was strongly influential in determining the shape of the civil rights movement in Seattle.

The Central Area Civil Rights Committee stood for fair housing, equal employment, and integration of public schools. It was involved in a number of campaigns to bring all of that to Seattle, but perhaps the most significant and contested of these was the integration campaign that began in 1964 and lasted through the dissolution of the organization in 1968.

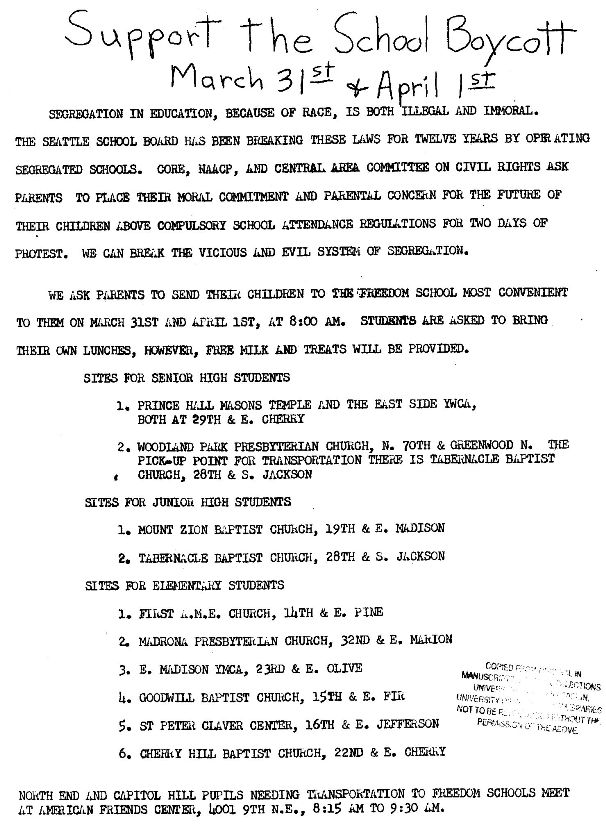

Although Seattle schools were technically desegregated, de facto segregation, based on the higher concentration of black families in poorer areas of the city like the Central District, had led to an uneven distribution of black students in the public schools. The schools that had the greatest numbers of black students were often in the worst condition. CACRC quickly took the unalterable position that African American students should be integrated into schools outside of the Central District. The Committee led a student boycott in 1966 and proposed a mandatory busing program that would transfer black students out of the Central District and would bring white students into the area.

While CACRC remained strong in its position on integration, a growing number of blacks in the community were beginning to disagree with the strategy. Many blacks in the Central District resented the CACRC for claiming to speak on behalf of all civil rights activists when new factions were emerging with different priorities for the civil rights agenda. The issue of school integration remained a contentious one, and by 1968 the infighting amongst civil rights leaders had become so significant that the CACRC had lost its position as the “single voice” of the movement.