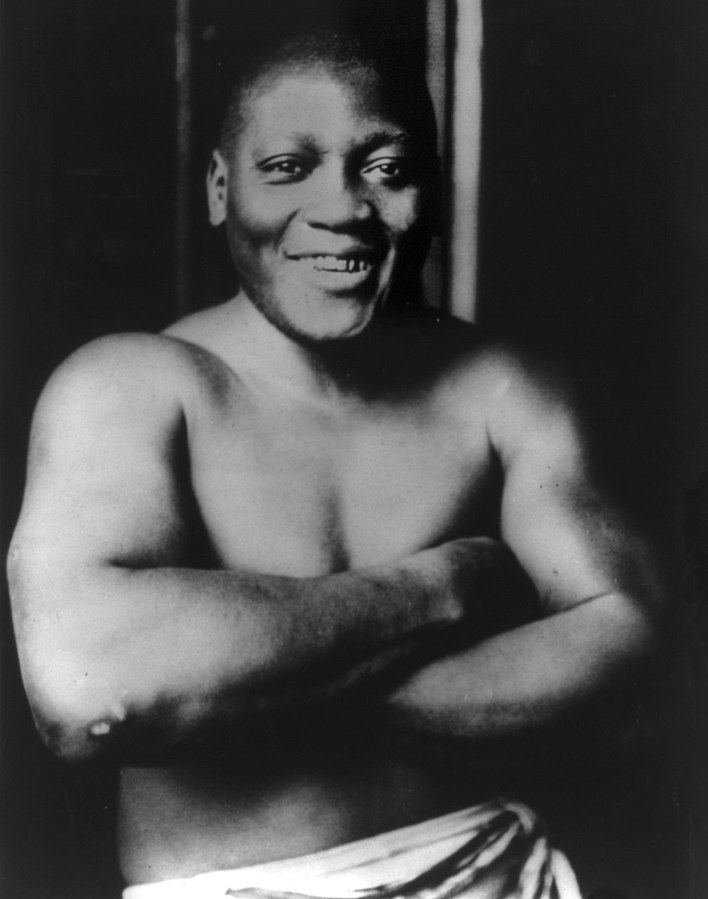

Jack Johnson, the first African American and first Texan to win the heavyweight boxing championship of the world, was born the second of six children to Henry and Tiny Johnson in Galveston on March 31, 1878. His parents were former slaves. To help support his family, Jack Johnson left school in the fifth grade to work on the dock in his port city hometown. In the 1890s Johnson began boxing as a teenager in “battles royal” matches where white spectators watched black men fight and at the end of the contest tossed money at the winner.

Johnson turned professional in 1897 but four years later he was arrested and jailed because boxing was at that time a criminal sport in Texas. After his release from jail he left Texas to pursue the title of “Negro” heavyweight boxing champion. Although he made a good living as a boxer, Johnson for six years sought a title fight with the white heavyweight champion, James J. Jeffries. Jeffries denied Johnson and other African American boxers a shot at his title and he retired undefeated in 1904.

Nevertheless, Johnson’s reputation as a skilled ring tactician continued to grow as he defeated both black and white boxers. Finally, in 1908, Johnson fought a white champion Tommy Burns in Australia for $30,000, then the highest purse in boxing history. Johnson knocked out Burns in the 14th round to become the first African American heavyweight champion of the world.

Johnson’s capture of the title initiated a search among white promoters for a “great white hope” to defeat the black champion and reclaim the title for white America. They eventually lured Jim Jeffries out of retirement to face Johnson. On July 4, 1910, in what would be billed as the “Battle of the Century,” Johnson finally fought and beat Jeffries in Reno, Nevada to retain his title. Newspapers warned Johnson and his supporters against gloating over the victory. Nonetheless, scores of African Americans and some whites died as a result of the race rioting that broke out in cities across the nation in response to Johnson’s victory. In fear of more race riots, the Texas legislature banned all films showing the black fighter’s wins over any of his white opponents.

Johnson also attracted considerable condemnation because of his unabashed sexual relationships with numerous white women. In 1913, Johnson fled the United States because federal officials charged him with violating the Mann Act, which prohibited the transportation of women across state lines for prostitution, debauchery, or immoral acts.

While in exile in Cuba, Johnson lost his title in 1914 to little known white boxer Jess Willard. Failing to get other matches abroad, Johnson returned to the U.S. in 1920 to surrender to Federal authorities. He was tried and convicted for violation of the Mann Act and sentenced to a year and a day in the Federal penitentiary at Leavenworth, Kansas. Ironically, Johnson was appointed athletic director of the prison while still an inmate. Upon his release from prison in 1921, he returned to the ring, participating only in exhibition fights. Promoters never again gave Johnson another title shot.

Jack Johnson married three white women in succession, Etta Duryea, Lucille Cameron, and Irene Pineau, but those unions failed to produce children. On October 6, 1946, after a North Carolina diner denied him service, he stormed out of the business and soon afterwards crashed his car. Johnson died from the impact. He was 68. The Boxing Hall of Fame posthumously inducted Johnson in 1954 and he received the same honor from the International Boxing Hall of Fame in 1990.