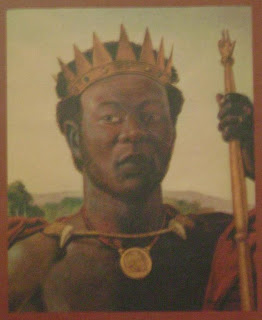

Miguel I de Buría, also known as King Miguel and Miguel the Black, was a formerly enslaved man from San Juan, Puerto Rico who ruled as the King of Buría in the modern-day state of Lara, Venezuela from 1552 to 1555. He is best known for leading a slave insurrection against the Spanish in 1552. Following that revolt Miguel established himself as the first king of the new state of Buría, while naming his wife, Guiomar, queen and his son as a prince. Miguel was the first and only king of African descent in Venezuela, serving for three years until he was killed in battle by Spanish forces in 1555.

Miguel was born around 1510 in San Juan, Puerto Rico. Little is known of his early life but he was brought to Venezuela by slaveowner Damian del Barrio and later inherited by his son, Pedro del Barrio. Miguel worked on the Real de Minas de San Felipe de Buría, which was a gold mine in the province of Yaracuy.

When a Spanish foreman, Diego Hernandez de Serpa, tried to punish him, Miguel resisted, grabbing a sword from the foreman and fighting him before escaping to the nearby Cordillera de Merida mountains. From his base in the mountains Miguel started a maroon colony and eventually led a rebellion of enslaved workers in the San Felipe Mines. Gathering weapons, Miguel and his followers attacked Spanish guards at the mines. They captured many of the guards and executed those who had been particularly cruel to the enslaved workers.

Having seized control of the mines, Miguel and his followers spread out across Yaracuy province freeing other enslaved people. He then led them back into the safety of the mountains. The actual location of Miguel’s maroon colony is unknown, but we do know that Miguel was made king of the settlement while his wife and son became the queen and prince. Other rebellion leaders became government ministers and military officers.

The Spanish colonial government in Venezuela, however, was determined to destroy the maroon colony of Buría. Anticipating an attack from Spanish colonial troops, Miguel led his forces against them at Nueva Segovia de Barquisimeto. Borrowing tactics from nearby indigenous tribes, they painted their faces using genipa Americana, a plant widely found in the region, to intimidate the Spanish soldiers. Miguel and his troops then attacked the town, burned a church, and killed a priest, Toribio Ruiz, and six settlers in 1555.

The war with the Spanish colonial army continued until Miguel was killed in battle later in 1555 while leading a charge against Spanish troops commanded by Captain Diego de Losada. After Miguel’s death, most of his demoralized followers who survived the battle were re-enslaved. Nonetheless the three-year resistance of Miguel and his followers in what would be one of the first challenges to Spanish colonial rule in Venezuela and the rest of Latin America, would become an important inspiration for Venezuelan folklore and literature.