Over the past seven decades the exploits of the Tuskegee Airmen have been celebrated, occasionally mythologized, and used as a recent reminder of the patriotism and heroism of African Americans in times of national crisis. Mounting pressure by black leaders such as union activist A Philip Randolph, NAACP chief executive Walter F. White, First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt and the black press to increase their presence in all branches of military service eventually persuaded a reluctant War Department to allow for the training of blacks as fighter pilots (initially no training for bomber crews) at an isolated field at Tuskegee Institute in Alabama, thus preempting contact with white trainees.

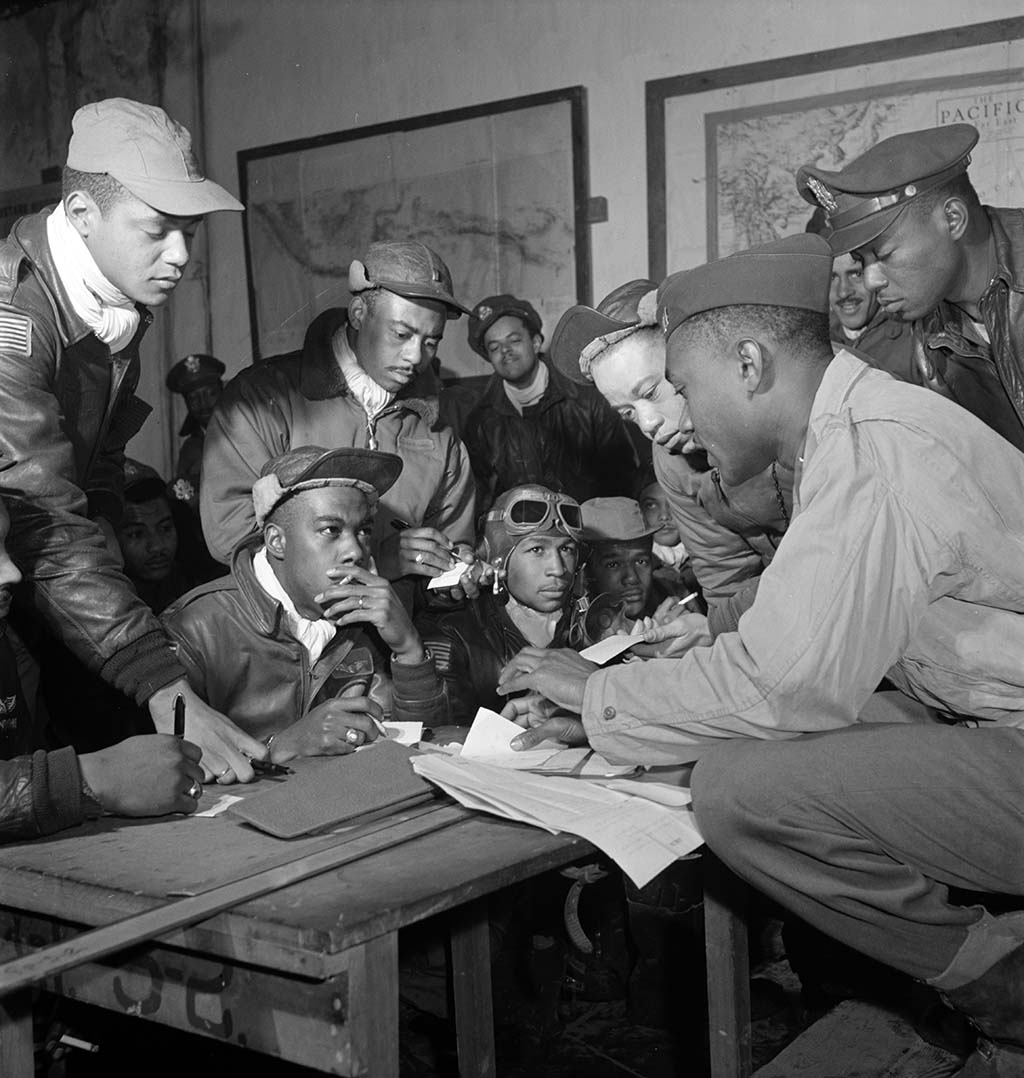

Courtesy Library of Congress (2007675064)

The legal authority to form a black combat flying unit sprang from Public Law 18, enacted in 1939, which directed the Civil Aviation Authority (CAA) to allow for the establishment of training programs for “Negro pilots” at designated locations, most notably Tuskegee Institute (now Tuskegee University) and a revised Selective Service Act in 1940 that effectively ended discrimination in the recruiting of men for the armed forces. Despite the strictures of brutal and demeaning segregation in the nation’s military and the actions of a few of its white commanders to retard their efforts, 992 African American flight cadets completed the Army Air Corps course between July 19, 1941 and the end of World War II including many who had originally been assigned to the old Buffalo Soldier units, the 9th and 10th cavalries and the 24th and 25th infantries. Also, because they were a segregated unit, supporting personnel who were black–bombardiers, navigators, mechanics, and instructors—also had to be trained and they too are considered Tuskegee Airmen who kept the pilots aloft.

Graduation of the first five pilots who received their wings took place on March 7, 1942, at the Tuskegee Army Air Field. Roughly 450 men joined the 99th Pursuit Squadron, initially led by whites but later ably commanded by then Capt. Benjamin O. Davis, Jr. who also took charge of the all-black 477th Bombardment Group in 1945. The 99th and the 332nd Fighter Group saw action in North Africa and Italy where they distinguished themselves winning hundreds of decorations for skill and gallantry in combat. Flying P-39 Airacobras, Curtiss P-40 Warhawks, P-47 Thunderbolts and, lastly, P-51 Mustangs, among the feats of the fighter pilots who flew more than 15,000 sorties was the downing of more than 100 enemy aircraft in aerial combat including three of Germanys fearsome ME-262, the world’s first operational fighter jet; demolishing nearly 150 enemy planes on the ground; and ruining an Italian destroyer that had been converted to a German torpedo boat.

The Tuskegee Airmen were prized and respected in the Army Air Force for their success in closely protecting Allied bombers flying missions into Axis territories. Moreover, their outstanding performance served to bolster African American pride and facilitated the transition to an integrated military in the post-war years. Among the Tuskegee Airmen emerged a number of future leaders including Air Force four-star generals Benjamin O. Davis Jr. and Daniel “Chappie” James, Maj. Gen. Lucius Theus, Detroit Mayor Coleman Young, New York Borough President Percy Sutton, pioneering San Francisco physician Wendell Lipscomb, and sociologist Dr. Dempsey W. Morgan.