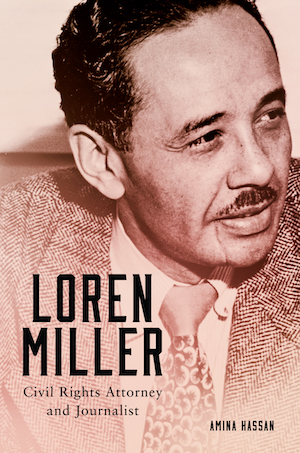

In the essay below, journalist and historian Amina Hassan describes her 2015 biography of Loren Miller, a significant but understudied figure in the long twentieth century campaign for civil rights and racial justice.

This book on Loren Miller’s life has its origins in my growing up in Los Angeles. As a child, I knew Miller’s name because he had represented my father, Alfred Hassan, who had been refused service by the Kansas City Steak House. This was in the days that my father, a former California State track champion, worked for the post office before he became a civil engineer. On the day he entered the restaurant; he was wearing his mail carrier’s uniform and was in the company of two white mailmen. Through the lawsuit, Miller succeeded in getting each of the three men the then-standard settlement of $100.

Although I knew that skeletal story, I asked my father only years later, while in the midst of this biography, just how he had come to know Miller. It was my mother, Mamie, he replied, who was the conduit. An early childhood educator with the Los Angeles Public Schools, she knew Loren Miller’s wife, Juanita, one of Southern California’s foremost social workers. Although we did not socialize with the Millers, we shared some similarities. We lived near their Silver Lake neighborhood, away from other black Angelenos; and we were educated, racially mixed, politically progressive, and secular. My parents—and what I later learned about Miller—believed wholeheartedly in exercising their constitutional rights without which they knew there is no democracy. So, it was no accident that Miller’s life intrigued me.

However, the clincher for my deciding to launch this project goes to the generosity of spirit of the library staff at the Huntington Library in San Marino, California. Before my first visit, I contacted the library staff who informed me that sixteen dusty cartons of Loren Miller’s papers had just arrived, and if I was interested, I should let them know when I arrive. When I did, I was asked if I would like to go to the basement to see what the cartons contained. There I discovered, along with staff curator Bill Frank, that we were the first to view these documents, which had been preserved but had languished for decades in Miller’s older son’s basement. I was asked if there were things I’d like to see, and if I did, I would be allowed a few hours’ access. Three dusty cartons were moved to an office for my viewing where I hastily examined the contents—barely able to contain my joy. It was then that I decided to begin working on a biography of Loren Miller. Within a year, the documents were cataloged.

But why write a book about a man few people have even heard of, a man who today is largely forgotten? Who was Loren Miller? What did he do? Why is he relevant?

Loren Miller was part of that group of brilliant NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund attorneys, led by Thurgood Marshall, who changed the course of United States history. This advocate for complete equality wrote the majority of the briefs in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas.

As a member of the American Civil Liberties Union of Southern California (ACLU-SC), Miller sought to halt the internment of West Coast Japanese, a monumental feat, considering that the NAACP, Jewish groups, the national office of ACLU had not stepped forward to stop the internment of Japanese Americans. Although I had heard stories that Miller held the deeds of his neighbors’ homes when they were carted off to the camps, when I wrote the book I had only anecdotal evidence. However, after its publication, I came across evidence that verifies that indeed he held his neighbors’ deeds as well as in their absence rented out the properties. Miller helped to integrate the Los Angeles Fire Department and the United States military. He helped to bring fair employment practices to Californians. From the 1930s to the 1960s, he wrote for many black newspapers and worked for such leftist publications as the New Masses. He co-founded in 1934, along with his cousin, The Los Angeles Sentinel, which today reaching 125,000 readers. In the 1950s, he bought one of the longest-running black newspaper in the west, The California Eagle.

And, in 1932, Miller traveled with his friend Langston Hughes to the Soviet Union to make a big budget film on black life, a trip that sealed their friendship for the next forty years.

This is a story of a man, more introvert than extrovert, who made the United States better not just for himself alone; a man who knocked down the last legal props of segregated housing and segregated education. He was born in 1903, the son of a former slave, who married a white woman. He grew up in immutable, unbearable poverty on a farm in Kansas. He wrote in his unpublished autobiographical novel of his childhood that one night “there was a sudden clamping of the trap and the squeal of the rat.” Before the night ended, his mother had caught fourteen rats. While he came from humble beginnings, his impact on our lives today is nothing short of extraordinary. He would attain truly herculean accomplishments, climbing out of the depths of staggering poverty; his life was a far cry from ramshackle homes and rats skittering around at night.

Miller was a fearless critic of the powerful and an ardent debater who understood that inequality and capitalism go hand in hand. He set out for Los Angeles from Kansas in 1929. He was a freshly minted member of the bar who preferred political activism and writing to the practice of law. He admitted that he was dragged kicking and screaming into the practice of law because, “you know, in those days,” he said, “a Negro could be a doctor, lawyer or school teacher—and that’s about all.” Not a man given to brooding or self-pity, Miller accepted the career path he chose.

Miller argued two landmark cases before the U. S. Supreme Court. In 1948 he argued the famous Shelley v. Kraemer case that all lawyers study in law school. Alongside Thurgood Marshall and Charles Hamilton Houston, Miller overturned racial restrictive housing covenants. Marshall would say that the Shelley case was “unquestionably, one of the most important in a whole field of civil rights.” Because Miller argued more restrictive covenant cases than any attorney did— more than one hundred—he earned the title of “Mr. Civil Rights of the Western United States.”

Although most people today are unaware of the central role Miller played in changing history, there were those who did. For example, Federal Appeals Court Justice A. Leon Higginbotham Jr., “in paying tribute to the black lawyers of our country,” said in 1979, “that one man who would have been, should have been an appellate judge or a member of the U. S. Supreme Court was the late Loren Miller.” Others felt that he was barely second in importance to Thurgood Marshall. Yet, during the fiftieth and sixtieth anniversary celebrations of Brown, the man who wrote the majority of the Brown briefs is not even mentioned. His erasure from our collective memory is a real travesty.

Additionally, what isn’t so widely known is that Miller, in 1945, before Brown v. Board of Education, was part of an important class action case in California. It challenged the constitutionality of segregating Mexican-American children from California’s public schools.

As a member of the National Lawyers Guild and the NAACP, he filed amici curiae (friend of the court) briefs in support of Mendez v. Westminster. It was “the first case to hold that school segregation itself is unconstitutional and violates the Fourteenth Amendment.” Later, he became chairman of the Community Service Organization (founded 1947), one of California’s first Latino organizations, most famous for training Cesar Chavez.

What is important about the Mendez case is that it was the first case to use sociological and psychological evidence to show how segregation damages children. This was before Brown v. Board of Education. The uniqueness of Brown is that it too used sociological data as evidence. That strategy, in many ways, led to the historic decision to end racial segregation in public schools. Although Loren did not argue Brown in court, he drafted most of the briefs.

At the same time that he worked on the Mendez case, Miller represented Hattie McDaniel, the first black woman to receive an Academy Award. She won an Oscar for her role in Gone with the Wind. She was being sued because she had the audacity to buy and live in a house in Los Angeles’s exclusive Sugar Hill District. Before she was sued, it was thought that there was little possibility that a black movie star would be forced to move. However, this was a time in Los Angeles when the only way a “negro” could live in a restricted area was as a servant. It was a time when the black residents of Los Angeles—fed up—filed more suits contesting the validity of restrictive covenants than in any part of the country.

On December 5, 1945, Hattie and her fifty co-defendants and hundreds of sympathizers “appeared in court in all their finery.” One writer said that the stylish atmosphere in the court “was such as to make one wonder if the judge would pour tea during the afternoon recess.”

Ultimately, they won what was considered the first covenant case on constitutional grounds. Afterward, Miller wrote a friend, “I rushed home to try the “Sugar Hill” restriction case and succeeded in pulling a rabbit out of the hat by inducing a local judge to hold race restriction covenants unenforceable on the grounds that such enforcement would violate the Fourteenth Amendment.” The Sugar Hill victory was a monumental moment because it set a U. S. precedent. On a personal note, for Miller, it was the first of many high-profile cases. All this from a humble man who fought injustice but whose natural demeanor was more like the quiet lion slowly pouncing to improve all of our lives for the better. Which he did.