In the account below University of Quebec at Montreal historian Greg Robinson describes the activies of Hugh MacBeth, a black Los Angeles attorney, on behalf of the Japanese American citizens and resident aliens incarcerated during World War II.

Hugh MacBeth, Sr., an African American attorney from Los Angeles, is largely forgotten today, but he deserves commemoration as an outstanding defender of Japanese Americans during World War II. MacBeth maintained close contacts with Japanese Americans. He settled in Los Angeles’s Jefferson Park, then largely Japanese. MacBeth’s son Hugh, Jr., who later became his law partner, recalled that as a child he attended Japanese school with his Nisei pals after school, since otherwise he had nobody in the neighborhood to play with. There Hugh, Jr. studied the Japanese language and Judo (and also absorbed community prejudices against Chinese and Filipinos!). Meanwhile, the MacBeth family informally took in an orphaned Nisei (second generation Japanese) boy, Kenji Horita.

In early January 1942, shortly after Pearl Harbor, MacBeth traveled to Guadalupe and Santa Barbara, California to investigate the cases of Issei (first generation Japanese) rounded up by the government during December and interned in Missoula, Montana. Following interviews with the internees’ families, he discovered that those taken were prosperous farmers, and that there was no evidence of sabotage. He swiftly concluded that the removal was engineered by white agricultural interests anxious to grab the Issei farmers’ land. Outraged, MacBeth turned to organizing support for Japanese Americans among liberal and church groups. Thanks to MacBeth, the California Race Relations Commission and the Santa Barbara Minister’s Alliance would become the only two Southern California organizations to officially oppose evacuation.

MacBeth simultaneously organized efforts nationwide. He corresponded with Socialist leader Norman Thomas, who used the information MacBeth provided in newspaper articles and radio speeches denouncing Executive Order 9066. MacBeth later co-signed Thomas’s pamphlet, “Democracy and the Japanese Americans.” The pamphlet–widely distributed by the Japanese American Citizens League–denounced the government’s policy as “totalitarian justice” and called for an end to evacuation and for reparations.

The announcement of Executive Order 9066 on February 19, 1942 was a blow to MacBeth. On February 22 he sent President Roosevelt a telegram, asking him, now that his order had allayed fears of sabotage, to permit “liberty-loving Japanese” to resume their agricultural activities “under military surveillance and with government assistance.” Meanwhile, he spoke privately of his grief at families being “torn up by the roots” and sent off from their homes “they know not where.” In March 1942, he wrote General John DeWitt to propose that loyal farmers be permitted to form cooperatives and establish colonies in Utah. (The plan was designed by Hi Korematsu, whose brother Fred would soon challenge evacuation.) MacBeth proceeded to lecture the General that removal reflected “general and deep seated American racial prejudice against orientals and particularly against Japanese.” Not unexpectedly, DeWitt failed to reply.

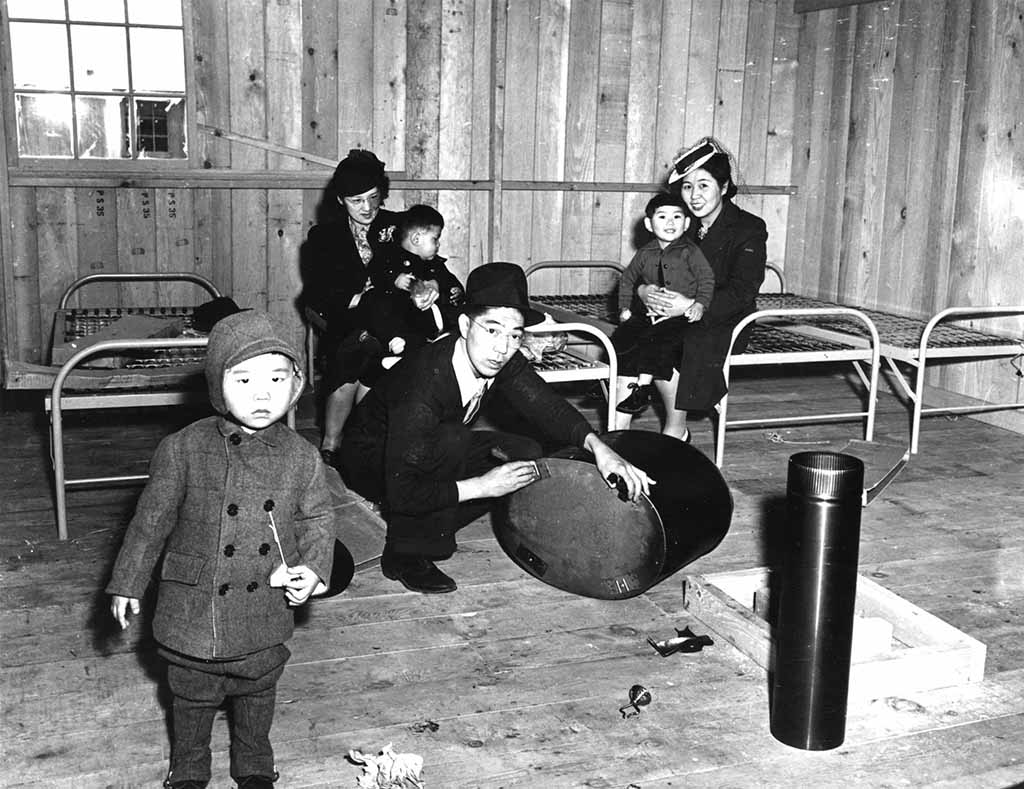

In May 1942, MacBeth visited Santa Anita Assembly Center with his wife and brother to see friends and collect information on conditions. Shortly afterwards, he traveled to Washington to brief Justice Department officials on Japanese Americans. (Using a White House cook as a back channel, Macbeth attempted without success to secure a meeting with President Roosevelt in order to lobby for an executive order making racial discrimination a military offense.)

Upon returning to California, MacBeth joined American Civil Liberties Union attorney A.L. Wirin in defending Ernest and Toki Wakayama. Ernest Kinzo Wakayama, born in Hawaii in 1897, was a union official, World War I veteran and officer of the American Legion, while Toki was a Nisei from California. The Wakayamas filed habeas corpus petitions asserting that there was no military necessity for evacuation and that DeWitt’s exclusion order was arbitrary and a violation of rights. In October 1942, a three-judge panel heard the petitions. In his supporting brief and in oral argument, MacBeth charged that race-based confinement constituted unconstitutional discrimination. On February 4, 1943, the judges granted a writ of habeas corpus. However, by that time the Wakayamas, worn down by large-scale beatings and ostracism at the Manzanar internment camp in Northern California, had withdrawn their suit and requested “repatriation” to Japan.

Despite this defeat, MacBeth continued to defend Japanese Americans. He repeatedly wrote War Relocation Authority (WRA) Director Dillon Myer with advice. At a public forum in Los Angeles in April 1943, he bravely spoke out in favor of letting Japanese Americans return to the West Coast. In 1944, he signed the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL) brief in the historic case of Korematsu v. United States. Shortly afterward, he traveled to the Amache internment camp to counsel families of Nisei draft resisters. When Chiyoko Sakamoto, the first Nisei woman to be admitted to the California Bar, returned from camp in mid-1945 and was unable to find work. MacBeth hired her as his associate.

In 1945, MacBeth and his son Hugh, Jr. joined JACL counsel A.L. Wirin in the case of Fred and Kojiro Oyama, who challenged California’s Alien Land Act which prevented Japanese immigrants from owning land. In February 1945, People v. Oyama, was argued in the San Diego County Superior Court. Wirin and Macbeth argued that alien land laws were out of date and penalized the defendants solely because of race. The judge ruled against the Oyamas, at which point MacBeth withdrew from the case. However, the decision was appealed, and ultimately reached the U.S. Supreme Court. In January 1948 the High Court granted victory to the Japanese couple. Oyama v. California not only ended all enforcement of the Alien Land Act, but furnished an important precedent for later rulings striking down racial segregation.

Hugh MacBeth died in 1956 in Los Angeles. Although his career is obscure, his passion for justice remains inspiring.