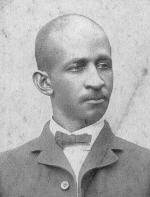

On August 6, 1945, Private First Class Malvin L. Brown was killed after falling 140 feet during a “let-down” from a tree while fighting a forest fire in the Umpqua National Forest in southern Oregon. Brown was the first smokejumper to die while fighting a wildfire since the program’s inception by the U.S. Forest Service in 1939. He was also the only member of the “Triple Nickles” 555th Parachute Infantry Battalion to die in the line of duty during World War II.

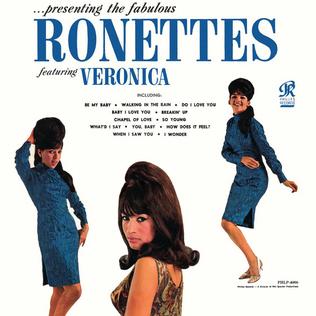

The 555th Parachute Infantry Battalion was nicknamed “Triple Nickles” because of its numerical designation and because 17 of its original 24 “colored test platoon” were from the 92nd Infantry (“Buffalo Soldiers”) Division of the U.S. Army. Their identifying symbol is three buffalo nickels joined in a triangle and the oddly-spelled “Nickle” is one of their trademarks.

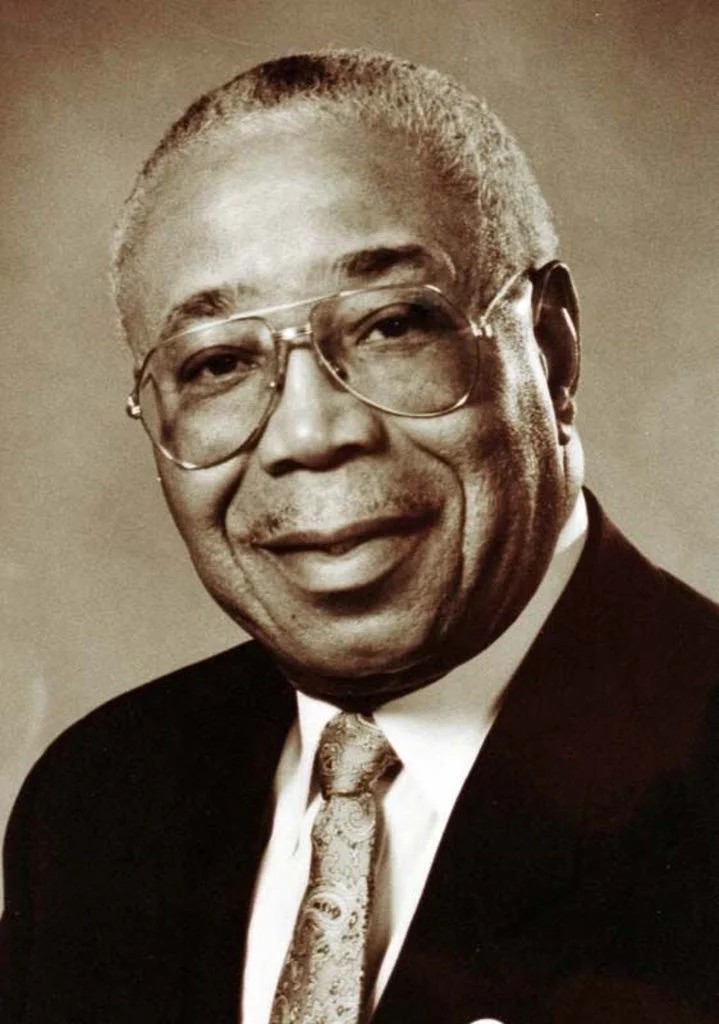

During the winter of 1943-1944, the first black paratroopers in army history began training at Fort Benning, Georgia. After several months, the segregated unit was moved to Camp Mackall, North Carolina, where it was reorganized and redesignated as Company A of the newly activated 555th Parachute Infantry Battalion. Unlike other African American infantry units officered by whites, the 555th was entirely black since six black officers also completed jump training.

By late 1944, the first platoon of Triple Nickles was fully trained, combat-ready, and alerted for European duty. The men were anxious to fight Hitler’s Nazis in Europe or the Japanese in the Pacific. Instead, racial military politics and changing war conditions kept the paratroopers home and away from the war they had been trained to fight.

On May 5, 1945, a Japanese incendiary balloon explosion killed the pregnant wife of a local minister and five young members of their church while on a Sunday picnic near Bly, Oregon. The Army kept the details of the incident a secret as they didn’t want members of the public to panic regarding the thousands of such balloon bombs that had been launched by the Japanese toward American shores, intended to start major forest fires and create just such fears.

In early 1945, the Triple Nickles had received secret orders from the War Department called “Operation Firefly.” They were sent to Pendleton, Oregon, assigned to the 9th Services Command, and trained by the Forest Service to become history’s first military smokejumpers. They were specifically designated to respond to Japanese balloon bombs.

During that year’s fire season, the Triple Nickles made more than 1,200 individual jumps and helped control at least 28 major fires although none were believed to have been caused by the Japanese. The paratroopers suffered numerous injuries but only one fatality: the day of Malvin Brown’s death, August 6, 1945, was also the day the United States dropped an atomic bomb on Hiroshima, Japan. Both events made the front page of the local newspaper in Roseburg, Oregon but the pioneer paratrooper’s death was barely noticed by comparison and soon forgotten.

In December 1947, the Triple Nickles were deactivated and their personnel were assigned to other Army units. One group, the 2nd Airborne Ranger Company, became the first black unit to make a combat jump during the Korean War. Ultimately, the Triple Nickles served in more airborne units, in peace and in war, than any other parachute group in history.