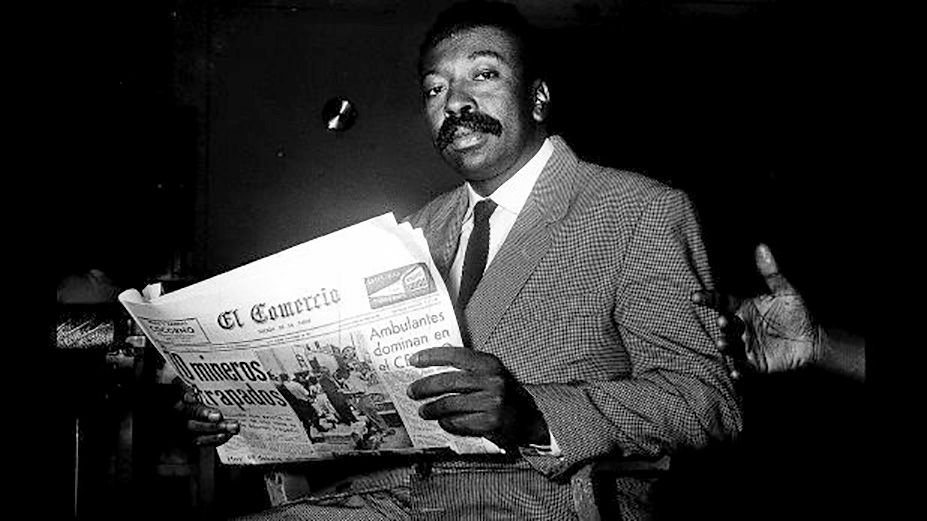

In the following article University of Oregon historian Carlos Aguirre describes the self-taught poet, writer, and folklorist Nicomedes Santa Cruz, one of the understudied black intellectual leaders in Peru and Latin America.

Nicomedes Santa Cruz was, without a doubt, the most important black intellectual in twentieth-century Peru, and one of the most important in Latin America. Yet, his life, work, and legacy remain relatively unknown, except within academic circles and among Afro-Peruvian organizations.

Between the late 1950s and 1992, the year of his death, he was a restless and passionate cultural entrepreneur, folklorist, poet, and playwright. He was in fact one of the most active intellectuals in Peru: he published about ten books in various genres, essays, short stories, and especially poetry (some of them with several reprints of up to 10,000 copies), hundreds of pieces in newspapers and magazines, and dozens of academic articles on different aspects of black history, culture, religion, poetry, oral traditions, music, and religion. He also recorded a dozen albums that sold thousands of copies, directed radio and TV programs, represented Peru in various international festivals, participated in numerous international conferences, and offered poetry readings in festivals and solidarity events in numerous countries.

Santa Cruz also wrote and directed plays and participated in the staging of theater and music performances. His audience and intellectual connections were not limited to Peru. He became acquainted with intellectuals in the Americas and around the world and conducted research and published works on black music and cultural traditions in other parts of the Americas such as Brazil, Cuba, Puerto Rico, and Panama.

But even more remarkable is the fact that Nicomedes Santa Cruz was a self-taught intellectual who never went to college and only completed elementary school. He was born in 1925 in a modest family that valued and practiced hard work and intellectual effort, but also preserved and cherished popular and Afro-Peruvian traditions. His father, also called Nicomedes, was a playwright of some success who had lived in the United States between 1881 and 1908, where he was trained as an electrician and mechanic, learned several languages, and nurtured a strong interest and taste for literature and music.

Nicomedes was born in La Victoria, a working-class district with a reputation of being one of the “blackest” areas of Lima, but the family later moved to Lince, a more socially and racially mixed district, when his father was hired to work as a mechanic in a rural estate, and then to Breña, another multi-racial, popular district of Lima. Being from a large family (Nicomedes was the ninth of ten children) and living with the relatively modest income generated by his father forced the young Nicomedes to seek a job as soon as he finished elementary school at the age of 11. He became an apprentice with a locksmith and later worked for many years as a blacksmith. While working for other patrons he started to write poetry during his idle time. He eventually opened his own shop in 1953 but closed it a few years later when he decided to spend most of his time recovering, recreating, and disseminating black and popular cultural traditions. He always referred to his working-class background with great appreciation and would continue to practice the trade from time to time in the midst of his usually busy schedule.

When Nicomedes was growing up as a talented and intellectually curious young man, Lima was still a patriarchal, seigniorial city, not particularly welcoming for blacks. Slavery had been abolished almost a century before, but blacks were still considered second-class citizens, their traditions and culture treated as inferior when not primitive, and the opportunities for their social, economic, and intellectual advancement were quite limited. But there was a vibrant tradition of black music, poetry, folklore, and jaranas (parties) that had existed since colonial times but was now gradually imposing itself on official and mestizo society and would eventually gain increasing recognition.

Three major themes informed the work of Nicomedes Santa Cruz from the mid-1950s through the early 1990s: a celebration of the importance and value of black culture, history, and traditions; the need to fight against racism and discrimination; and his commitment to social justice and anti-imperialism. He was the first black intellectual to merge in his work and efforts an agenda for social justice with a deep preoccupation to fight against black people’s invisibility and oppression.

The struggle against racism would remain at the center of his political and intellectual preoccupations for the rest of his life. According to his account, he first became aware of racism when he fell in love with a girl and wanted to marry her, but his family did not agree: “My family did not accept my marriage with her, for the usual reasons [alleging that] ‘we have to improve the race.’” Later, he also realized that black historical figures were being silenced or did not appear in the standard historical and literary accounts. Blacks were in fact invisible. “All of this, stated Nicomedes in an interview, generated hatred in me against these silences, and later I became conscious of the task I had to fulfill, which may be accomplished using poetry as denunciation.”

He wrote indeed many poems that denounced racism. In an early piece entitled “De ser como soy” (“Of being like I am,” 1949), he wrote: “I’m pleased to be what I am / it is an ignorant who criticizes / that my color is black / that doesn’t hurt anybody (…) to be born of any color / that doesn’t hurt anybody.” In another poem, “Oiga usté, señor dotor” (“Listen, Mr. Doctor,” 1961), he wrote: “Listen, Mister / I don’t forgive you the insult / we poor people of my color / know of dignity / and live with honor.” And in “Fue mucho el tejemaneje” (“Too much manipulation,” 1965), he satirized a congress of (predictably conservative and white) historians that gathered to discuss mestizaje (racial and cultural miscegenation) in Peru: “In the country of complexes / and discrimination / a big meeting was organized / to study the pelt (…) because in this bad crucible / that who has one eighth of whiteness / shows off the belly like a turkey / and looks over the shoulder / at the black with amazement / and at the cholo with scorn.” Several articles written by Nicomedes in newspapers and magazines over the years addressed racism as well.

Not surprisingly, Santa Cruz was also the victim of negative and even racist attacks, especially after 1975, when the nationalist military government of Velasco Alvarado, with which he had collaborated, was toppled by a more conservative military regime and Santa Cruz began to lose influence in cultural circles. An intellectual who had worked so hard to eliminate racism, social injustice, and cultural divisiveness in Peru, ended up filled with pessimism and a sense of defeat.

In late 1980 Nicomedes decided to leave Peru and settle in Spain, his wife’s mother country. There, he finished one of his most important works, La décima en el Perú, a superb study and anthology of the genre that was published in Lima in 1982. (A décima is a ten-line stanza of Spanish origin that became very popular in Spanish America. It is still practiced in countries such as Puerto Rico, Peru, and Colombia, where it has become a genre associated with popular poets and troubadours.) That same year he began to direct, with great success, a cultural program for the Spanish international public radio station. In 1988 he was diagnosed with lung cancer and underwent surgery, with seemingly good results. He resumed his work on the radio and became involved in many activities related to the Quincentennial commemoration of Columbus’s arrival in America. On February 5, 1992, Nicomedes Santa Cruz died at the age of 66.

The most important black intellectual in twentieth-century Peru died away from home. His work and legacy, despite some important recent efforts, remain unknown for most Peruvians. A man of commitment and courage, of immense talent and creativity, of sincere dedication to the cause of black emancipation and social justice, Nicomedes Santa Cruz deserves to be recognized as one of the most accomplished poets and intellectuals in twentieth-century Peru, someone who devoted his life to the cause of human dignity for all, regardless of skin color.