The Mau Mau Uprising, a revolt against colonial rule in Kenya, lasted from 1952 through 1960 and helped to hasten Kenya’s independence. Issues like the expulsion of Kikuyu tenants from settler farms, loss of land to white settlers, poverty, and lack of true political representation for Africans provided the impetus for the revolt. During the eight-year uprising, 32 white settlers and about 200 British police and army soldiers were killed. Over 1,800 African civilians were killed and some put the number of Mau Mau rebels killed at around 20,000. Although the Uprising was directed primarily against British colonial forces and the white settler community, much of the violence took place between rebel and loyalist Africans. Thus the uprising often had the appearance of a civil war with atrocities on both sides.

The uprising, which involved mostly Kikuyu people, the largest ethnic group in the colony, began to take shape when more radical Kikuyu militants were invited in to the nationalist KAU (Kenya African Union). Called Muhimu, these activists replaced a more moderate, constitutional agenda with a militant one. The Muhimu began widespread Kikuyu oathing, often through intimidation and threats. Traditional oathing ceremonies were believed to bind people to the cause, with dire consequences like death resulting on the breaking of such oaths. The British responded with de-oathing ceremonies. Additionally, the Muhimu attacked loyalists and white settlers.

Although the exact origins of the conflict are in dispute, the war officially began in October 1952 when an emergency was declared and British troops were sent to Kenya. The British response to the uprising entailed massive round-ups of suspected Mau Mau and supporters, with large numbers of people hanged and up to 150,000 Kikuyu held in detention camps.

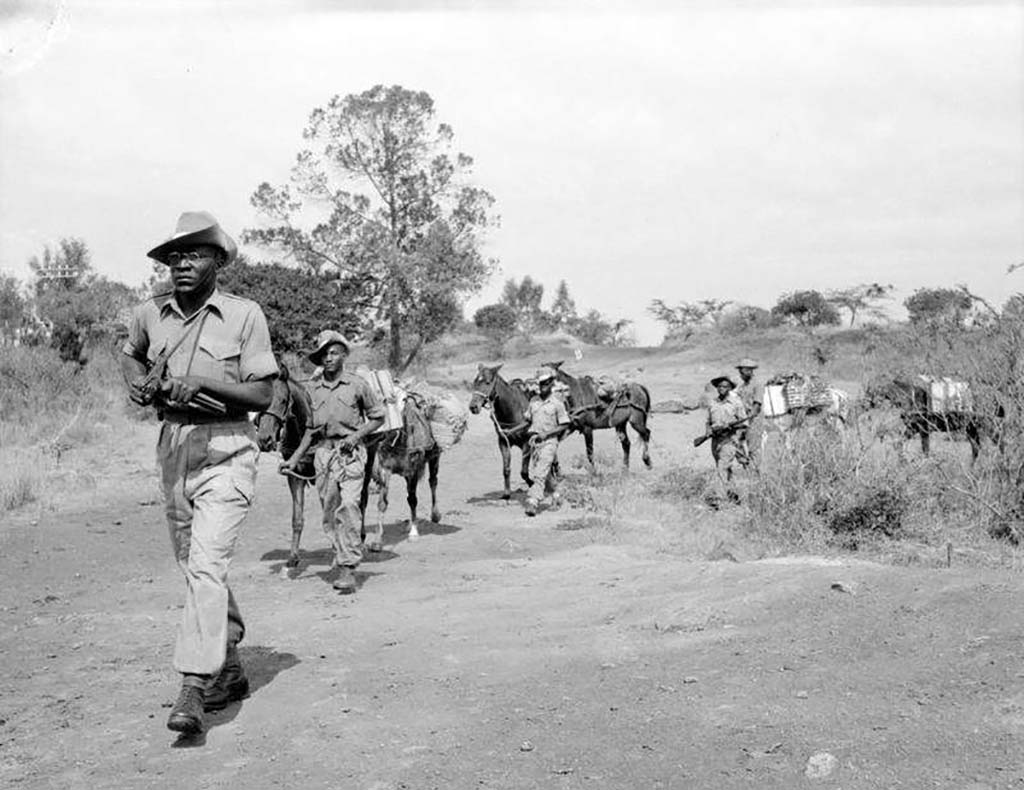

Many Mau Mau rebels and armies based themselves in forest areas of Mt. Kenya and Aberdares. Urban militants, however, waged the struggle in Nairobi and other Kenyan cities. The largest single massacre of the uprising took place in Lari on March 26, 1953, with attacks by Mau Mau on loyalist Home Guard families. Approximately 74 people were killed and about 50 wounded. The massacre generated retaliatory attacks by Home Guard, settler, and colonial forces. The initial massacre and retaliatory attacks resulted in the deaths of around 400 people, although there is no official number and the reality of people killed may have been much higher. The Lari Massacre was a turning point in the Uprising where many Kikuyu were forced to choose sides in this resistance struggle.

Mau Mau forest armies were largely broken by 1957 and in 1960 the emergency was declared over. Following the rebellion, the British government did implement reforms. Three years later, in 1963, Kenya received its independence from Great Britain. One of the alleged Mau Mau leaders, Jomo Kenyatta, became the first president of the new nation.

Historians, social commentators, and surviving resistance leaders continue to debate the role of the Mau Mau in gaining Kenyan independence. Many survivors on both sides of the conflict see themselves as participants in the independence campaign. Moreover, in 2006, former Mau Mau fighters launched legal action against the British government under claims of mistreatment in detention camps.