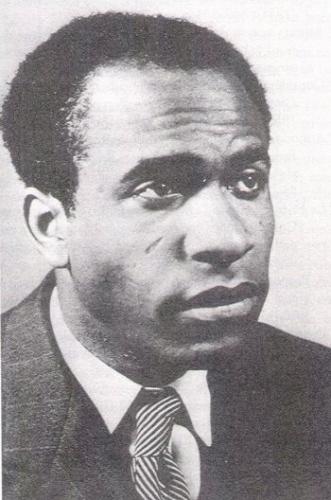

Psychiatrist and anti-colonial cultural theorist, Frantz Fanon was born in the French West Indies, in Fort-de-France, Martinique on July 20, 1925. His father, Félix Casimir Fanon, was a black customs service inspector. His mother, Eléanore Médélice, was half French and owned a hardware and drapery shop.

Fanon studied at Lycée Schoelcher, the secondary school in Fort-de-France until it closed down due to Vichy rule. The heavy-handed command of Vichy formed the young Fanon’s perspective on race relations. When Lycée Schoelcher re-opened in 1941, Frantz Fanon studied under the t poet Aimé Césaire. Under Césaire, a man who asserted black dignity through his concept of Negritude, Fanon’s understanding of his identity dramatically shifted. His studies had previously favored European and French worldviews, but from Césaire, Fanon felt himself more and more linked to his African roots.

In 1943, Fanon left for Dominica to enlist in the Free French forces. He served in Morocco and Algeria in 1944 and 1945, and then participated in the battle for Alsace. Though Fanon was commended for his bravery, the racism he experienced in the army led him to reject WWII as a white man’s war. He returned to Fort-de-France even more committed to his identity as a black man, rather than a European. In 1946, he enrolled in the University of Lyon where he studied psychiatry. With this degree, Fanon applied psychiatric theories to his personal experiences as a Europeanized West Indian. This application is seen in his published book, Peau noire, masques blancs (Black Skin, White Masks), 1952. A year later, he was assigned to head the psychiatric division of a hospital in Algeria. He joined the Algerian liberation movement when the insurrection against French rule began in 1954.

Fanon married Marie-Josephe Dublé in 1952, with whom he had his second child Olivier in 1955. His first child, Mireille, was born in 1948 to another woman. By 1956, he exiled himself to Tunis where he was the editor of Al Moujahid, a revolutionary Algerian newspaper. Fanon’s work in North Africa established him in the political domain. His subsequent books, Studies in a Dying Colonialism (1959) and The Wretched of the Earth (1961), would give a voice to the Third World liberation struggles of that time. With as varied disciplines as psychology, sociology, economics, and politics, all of Fanon’s works grapple with social justice and racism on an internal level as well as in the interaction between the colonizers and colonized.

In 1961, Fanon was diagnosed with leukemia, and was sent to the United States for treatment. At the early age of thirty-six, Frantz Fanon died in Bethesda, Maryland on December 6, 1961. His body was sent back to Tunisia to be buried.