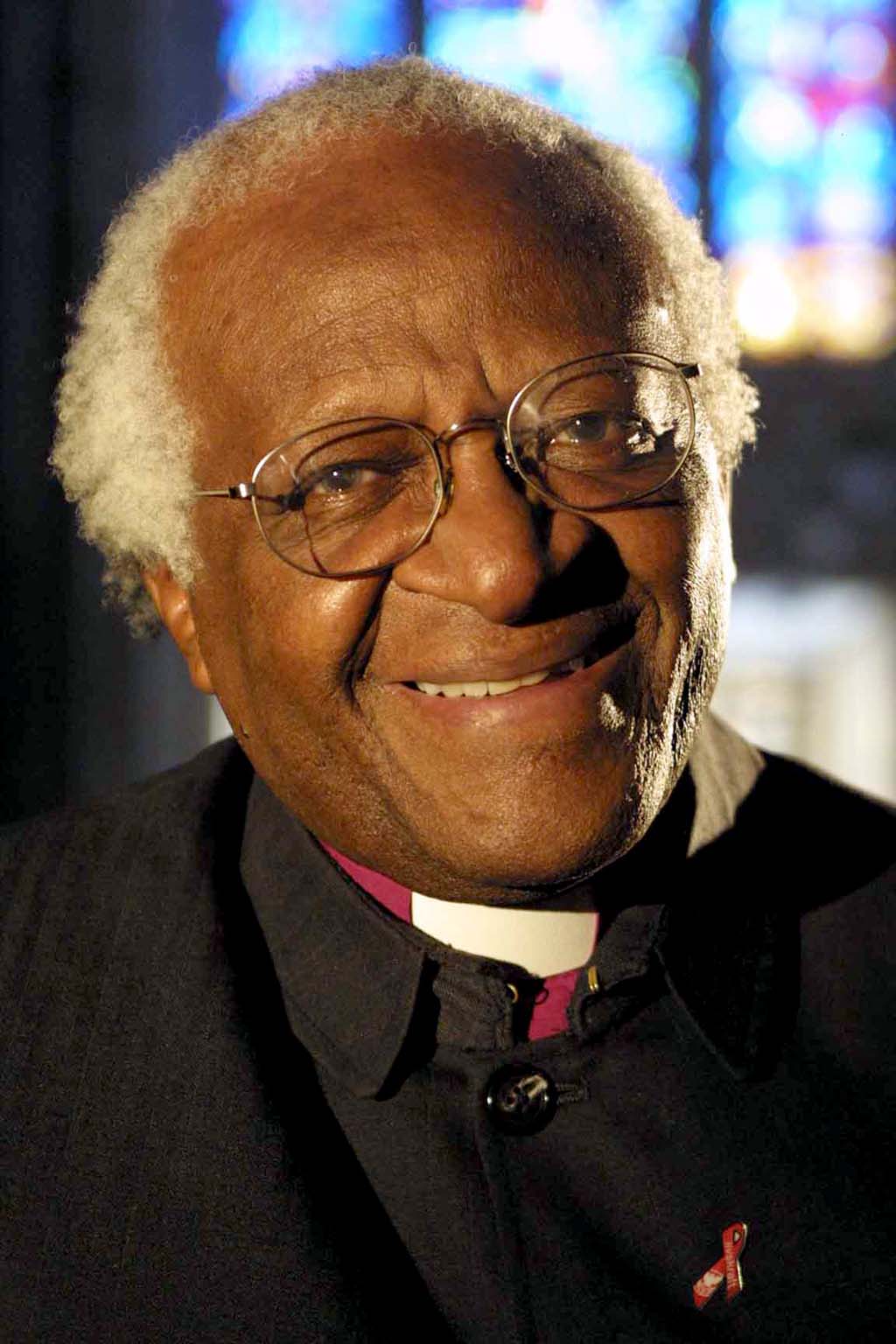

By the early 1970s South African cleric Desmond Mpilo Tutu had not yet achieved worldwide fame as an opponent of Apartheid. Nonetheless, in a July 1973 paper delivered to the National Conference of the South African Council of Churches, Tutu explained to his audience the growing anger and frustration among the opponents of Apartheid against the injustices routinely inflicted on the black population. His paper appears below.

It is generally unacceptable to most people in the world today that a minority should rule the majority without the consent of the latter. Now this is the position in which we find ourselves in South Africa at the present time. And the majority are demanding what they consider to be their inalienable right to self-determination.

The second horn of the dilemma apparently is that the minority, because they have enjoyed such wonderful privileges are determined to retain their privileged position and refuse to consider movement to an open and more just society, one which would rule the roost with the advent of so-called majority rule. The minority fear mainly because it is alleged that majority rule in other parts of Africa has brought in its train considerable chaos and misrule. What we have is, in fact, more an impasse than a dilemma, though the two courses just described are undesirable seen from a particular point of view. The first course-retention of white minority rule- is wholly unacceptable to the blacks, while majority rule is equally unacceptable to most whites.

One of the major questions we need to ask is whether we all still have sufficient control over things to be able to determine how history will develop. Some of us think that there might just still be time for us to discuss with one another — the ruled and the ruler, the privileged and the disadvantaged, the oppressor and the oppressed — for us to emerge into the sort of society in which every person will count for something because he or she is a human being first and foremost. So majority rule is rejected as unacceptable by whites and minority rule is rejected as unacceptable by blacks.

What one fears is that we may soon be overtaken by events of which the recent disturbances in black townships are perhaps harbingers, such that especially the white man will not have the possibility of exercising any options. He will be compelled to go along with a violent current — and so many of us want desperately to avoid this kind of thing happening. My worry is that it may be that we have another Pharaoh—Moses situation. You will recall how Moses kept going back to Pharaoh to warn him that God said unless he let the children of Israel go free, then all kinds of disaster would befall Egypt. You will recall that Pharaoh became more and more obdurate — he hardened his heart. It seemed that the warnings had the effect of rendering Pharaoh quite incapable of hearing and so acting rationally — he was set on a collision course with history and that was that.

Those who wield power and their supporters, mainly the white community in this country at the moment, are set on a collision course with history and are on the slippery slope to disaster unless they heed the many warnings that have been sounded and keep being uttered. Their reaction to events has been to become more intransigent and to adopt ever more draconian powers, dangerously unaware that the law of diminishing returns applies in this area of human relations as well. They will have to become more and more ruthless, unjust and repressive, gaining ever less and less security and peace, law and order.

There was a time in England when it was a capital offence to steal but such a stringent law failed to be a deterrent. Actually it made people more reckless since they said ‘one might just as well be hung for a sheep as for a lamb’. We will soon reach such a stage in South Africa when the victims of our ruthless and unjust laws will say ‘to hell with everything — I don’t mind what I do because it will be part of my contribution to the struggle for liberation. After all, we are detained in solitary confinement for needless periods just because we want to be treated as what we are — human beings — and even when we are not harassed by the police and other authorities, when we are not banned and placed under house arrest or restricted in one form or another, our lives in the townships are not really worth living. To die because I have struck a blow for freedom is to have attained a new dignity that was denied me when I was alive.’

Please will somebody realize that the man who shot the Krugersdorp Municipal officials was issuing a serious warning that this is how most blacks feel. Please, please, wake up to the fact that we have been using euphemisms when we have been talking about black resentment and frustration. We have not wanted to shock whites or ourselves by telling it as it is, because what is filling black hearts more and more is naked hatred. I am frightened but that is just the plain truth — when a black confirmation candidate aged 16 years can say ‘I don’t want to be confirmed by a white bishop’ then we have reached a very serious state of affairs. God help us.

The object of our present exercise here, and the S.A.C.C. must be warmly commended for its courage and perspicacity — the object of the exercise is surely to point to a third possibility which is our best chance and that is for all of us to get together and to try to work out together the best and most just ordering of our society as possible. We must desperately, urgently, get down to the business of discussing and talking together, arguing with and persuading one another, giving what is due to one another and respecting one another’s point of view. Maybe it is now almost utopian — I hope not. The solution for our country must be one that we all accept freely and not one that is imposed, because we are creatures who have been created freely and made for freedom.

Yes, the oppressed must be set free because our God is the God of the exodus, the liberation God who is encountered in the Bible for the first time as a liberator striding forth with an outstretched arm to liberate the rabble of slaves, to turn them into people for his possession, for the sake of all his creation. This liberation is one that is absolutely crucial for both the oppressor and the oppressed, for freedom is indivisible. One section of the community can’t be truly free whilst another is denied a share in that freedom. And we are involved in the black liberation struggle because we are also deeply concerned for white liberation.

The white man will never be really free until the black man is wholly free, because the white man invests enormous resources to try to gain a fragile security and peace, resources that should have been used more creatively elsewhere. The white man must suffer too because he is bedeviled by anxiety and fear and God wants to set him free, to set us all free from all that de-humanizes us together, to set us free for our service of one another in a more just and more open society in South Africa, where true peace, justice and righteousness will prevail, where we will have real reconciliation because we will all be persons in a society where our God-given dignity is respected, where we will be free to carry out the obligations and responsibilities for being human, in which governments and other authorities will be strictly defined so that they do not blasphemously arrogate to themselves powers that no human being should exercise, where we will be able to protest against unjustified inroads on our liberty (something which is nonexistent in the white community, showing just how far we have fallen short of our calling to be human persons).

The struggle for liberation, a truly biblical struggle, is crucial for the survival of South Africa. It must succeed. Yes, liberation is coming because our God is the God of the Exodus, the liberator God. ‘If God is on our side, who is against us?’ (Romans 8: 32)