Dennis Brutus was a South African poet, organizer and activist perhaps most notable for his use of sports as a weapon against apartheid. Dennis Vincent Brutus was born to South African parents of French, Italian and African descent in Salisbury, Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) in 1924. When he was four, his family returned to Port Elizabeth, South Africa where, under the country’s racial code, Brutus was classified as “colored.” After graduating from the University of Fort Hare, Brutus became a teacher of English and Afrikaans in nonwhite schools.

While teaching, Brutus grew increasingly involved in the underground anti-apartheid movement. He was particularly drawn to the politics of sports due to the South African government’s practice of passing over talented black athletes in favor of less skilled white ones for internationally competing teams. To combat the practice, Brutus became involved in the creation of the South African Sports Association (SASA) in 1958. The goal of SASA was to encourage the integration of sporting bodies. In 1962, Brutus became the president of the newly launched South African Non-Racial Olympic Committee (SAONGA), intended to gain recognition from the International Olympic Committee over the discriminatory South African Olympic and National Games Association. The South African government subsequently banned SAONGA, and in 1963 Brutus was jailed for his involvement. However, while imprisoned on Robben Island, Brutus received word that, due in large part to his efforts, South Africa had been suspended from the 1964 Olympic Games, a ban which would soon be extended to include almost all international sporting events until 1991.

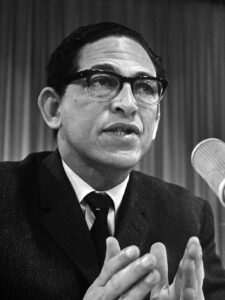

Photo by Eric Koch, Courtesy Netherlands National Archives (2.24.01.05), Public domain

In 1966, Brutus left South Africa for the United Kingdom, where he worked as a teacher and journalist, and then moved to the United States, joining the faculty at the University of Denver (Colorado). In 1971 Brutus became professor of African Literature at Northwestern University in Illinois. Twelve years later in 1983, Brutus found himself the subject of a highly publicized deportation case due to his lack of proper immigration paperwork. He was prominently supported in his fight to remain in the United States by U.S. anti-apartheid activists who contended that Brutus was being persecuted by the Reagan Administration for his race and political leanings. Ultimately, Brutus was granted political asylum when a judge ruled that his life would be endangered by a return to South Africa.

Dennis Brutus also wrote poetry that reflected the struggle against apartheid. His first collection, Sirens, Knuckles, and Boots, was published in 1963 while Brutus was imprisoned. Brutus’s literature was noted for its surprising restraint and the absence of anger and frustration at the apartheid system.

Dennis Brutus eventually returned to South Africa and died in Cape Town on December 26, 2009.