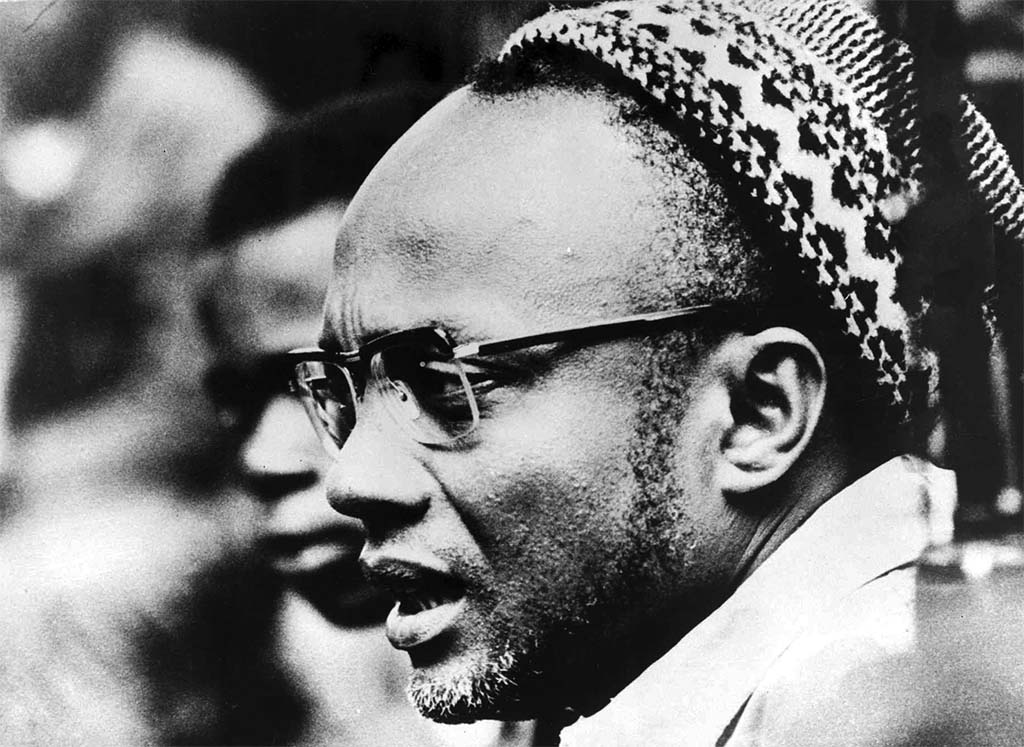

In 1966 Amilcar Cabral was the Secretary-General and President of the War Council of the P.A.I. G. C. (African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cape Verde). In January 1966 he delivered an address to the first Tricontinental Conference of the peoples of Asia, Africa and Latin America sponsored by Fidel Castro and held in Havana. His address appears below.

If any of us came to Cuba with doubts in our mind about the solidity, strength, maturity and vitality of the Cuban Revolution, these doubts have been removed by what we have been able to see. Our hearts are now warmed by an unshakeable certainty which gives us courage in the difficult but glorious struggle against the common enemy: no power in the world will be able to destroy this Cuban Revolution, which is creating in the countryside and in the towns not only a new life but also—and even more important—a New Man, fully conscious of his national, continental and international rights and duties. In every field of activity the Cuban people have made major progress during the last seven years, particularly in 1965, Year of Agriculture.

We believe that this constitutes a particular lesson for the national liberation movements, especially for those who want their national revolution to be a true revolution. Some people have not failed to note that a certain number of Cubans, albeit an insignificant minority, have not shared the joys and hopes of the celebrations for the seventh anniversary because they are against the Revolution. It is possible that others will not be present at the celebrations of the eighth anniversary, but we would like to state that we consider the ‘open door’ policy for enemies of the Revolution to be a lesson in courage, determination, humanity and confidence in the people, another political and moral victory over the enemy; and to those who are worried, in a spirit of friendship, about the dangers which may be involved in this exodus, we guarantee that we, the peoples of the countries of Africa, still completely dominated by Portuguese colonialism, are prepared to send to Cuba as many men and women as may be needed to compensate for the departure of those who for reasons of class or of inability to adapt have interest or attitudes which are incompatible with the interests of the Cuban people. Taking once again the formerly hard and tragic path f our ancestors (mainly from Guinea and Angola) who were taken to Cuba as slaves, we would come now as free men, as willing workers and Cuban patriots, to fulfill a productive function in this new, just and multi-racial society, and to help and defend with our own lives the victories of the Cuban people. Thus we would strengthen both all the bonds of history, blood and culture which unite our peoples with the Cuban people, and the spontaneous giving of oneself, the deep joy and infectious rhythm which make the construction of socialism in Cuba a new phenomenon for the world, a unique and for many unaccustomed event.

We are not going to use this platform to rail against imperialism. An African saying very common in our country says:

‘When your house is burning, it’s no use beating the tom-toms.’ On a Tricontinental level, this means that we are not going to eliminate imperialism by shouting insults against it. For us, the best or worst shout against imperialism, whatever its form, is to take up arms and fight. This is what we are doing, and this is what we will go on doing until all foreign domination of our African homelands has been totally eliminated.

Our agenda includes subjects whose meaning and importance are beyond question and which show a fundamental preoccupation with struggle. We note, however, that one form of struggle which we consider to be fundamental has not been explicitly mentioned in this programme, although we are certain that it was present in the minds of those who drew up the programme. We refer here to the struggle against our own weaknesses. Obviously other cases differ from that of Guinea; but our experience has shown that in the general framework of daily struggle this battle against ourselves—no matter what difficulties the enemy may create—is the most difficult of all, whether for the present or the future of our peoples. This battle is the expression of the internal contradictions in the economic, social, cultural (and therefore historical) reality of each of our countries. We are convinced that any national or social revolution which is not based on knowledge of this fundamental reality runs grave risk of being condemned to failure.

When the African peoples say in their simple language that ‘no matter how hot the water from your well, it will not cook your rice’, they express with singular simplicity a fundamental principle, not only of physics, but also of political science. We know that the development of a phenomenon in movement, whatever its external appearance, depends mainly on its internal characteristics. We also know that on the political level our own reality—however fine and attractive the reality of others may be—can only be transformed by detailed knowledge of it, by our own efforts, by our own sacrifices. It is useful to recall in this Tricontinental gathering, so rich in experience and example, that however great the similarity between our various cases and however identical our enemies, national liberation and social revolution are not exportable commodities; they are, and increasingly so every day, the outcome of local and national elaboration, more or less influenced by external factors (be they favourable or unfavourable) but essentially determined and formed by the historical reality of each people, and carried to success by the overcoming or correct solution of the internal contradictions between the various categories characterising this reality. The success of the Cuban revolution, taking place only 90 miles from the greatest imperialist and anti-socialist power of all time, seems to us, in its content and it way of evolution, to be a practical and conclusive illustration of the validity of this principle.

However we must recognise that we ourselves and the other liberation movements in general (referring here above all to the African experience) have not managed to pay sufficient attention to this important problem of our common struggle.

The ideological deficiency, not to say the total lack of ideology, within the national liberation movements—which is basically due to ignorance of the historical reality which these movements claim to transform—constitutes one of the greatest weaknesses of our struggle against imperialism, if not the greatest weakness of all. We believe, however, that a sufficient number of different experiences has already been accumulated to enable us to define a general line of thought and action with the aim of eliminating this deficiency. A full discussion of this subject could be useful, and would enable this conference to make a valuable contribution towards strengthening the present and future actions of the national liberation movements. This would be a concrete way of helping these movements, and in our opinion no less important than political support of financial assistance for arms and such like.

It is with the intention of making a contribution, however modest, to this debate that we present here our opinion of the foundations and objectives of national liberation in relation to the social structure. This opinion is the result of our own experiences of the struggle and of a critical appreciation of the experiences of others. To those who see in it a theoretical character, we would recall that every practice produces a theory, and that if it is true that a revolution can fail even though it be based on perfectly conceived theories, nobody has yet made a successful revolution without a revolutionary theory.

Those who affirm—in our case correctly—that the motive force of history is the class struggle would certainly agree to a revision of this affirmation to make it more precise and give it an even wider field of application if they had a better knowledge of the essential characteristics of certain colonised peoples, that is to say peoples dominated by imperialism. In fact in the general evolution of humanity and of each of the peoples of which is is composed, classes appear neither as a generalised and simultaneous phenomenon throughout the totality of these groups, nor as a finished, perfect, uniform and spontaneous whole. The definition of classes within one or several human groups is a fundamental consequence of the progressive development of the productive forces and of the characteristics of the distribution of the wealth produced by the group or usurped from others. That is to say that the socio-economic phenomenon ‘class’ is created and develops as a function of at least two essential and interdependent variables—the level of productive forces and the pattern of ownership of means of production. This development takes place slowly, gradually and unevenly, by quantitative and generally imperceptible variations in the fundamental components; once a certain degree of accumulation is reached, this process then leads to a qualitative jump, characterised by the appearance of classes and of conflict between them.

Factors external to the socio-economic whole can influence, more or less significantly, the process of development of classes, accelerating it, slowing it down and even causing regressions. When, for whatever reason, the influence of these factors ceases the process reassumes its independence and its rhythm is then determined not only by the specific internal characteristics of the whole, but also by the resultant of the effect produced in it by the temporary action of the external factors. On a strictly internal level the rhythm of the process may vary, but it remains continuous and progressive. Sudden progress is only possible as a function of violent alternations—mutations—in the level of productive forces or in the pattern of ownership. These violent transformations carried out within the process of development of classes, as a result of mutations in the level of productive forces or in the pattern of ownership, are generally called, in economic and political language, revolutions.

Clearly, however, the possibilities of this process are noticeably influenced by external factors, and particularly by the interaction of human groups. This interaction is considerably increased by the development of means of transport and communication which has created the modern world, eliminating the isolation of human groups within one area, of areas within one continent, and between continents. This development, characteristic of a long historical period which began with the invention of the first means of transport, was already more evident at the time of the Punic voyages and in the Greek colonisation, and was accentuated by maritime discoveries, the invention of the steam engine and the discovery of electricity. And in our own times, with the progressive domesticization of atomic energy it is possible to promise, if not to take men to the stars, at least to humanise the universe.

This leads us to pose the following question: does history begin only with the development of the phenomenon of class, and consequently of class struggle? To reply in the affirmative would be to place outside history the whole period of life of human groups from the discovery of hunting, and later of nomadic and sedentary agriculture, to the organisation of herds and the private appropriation of land. It would also be to consider—and this we refuse to accept—that various human groups in Africa, Asia and Latin America were living without history, or outside history, at the time when they were subjected to the yoke of imperialism. It would be to consider that the peoples of our countries, such as the Balantes of Guinea, the Coaniamas of Angola and the Macondes of Mozambique, are still living today—if we abstract the slight influence of colonialism to which they have been subjected— outside history, or that they have no history.

Our refusal, based as it is on concrete knowledge of the socioeconomic reality of our countries and on the analysis of the process of development of the phenomenon ‘class’, as we have seen earlier, leads us to conclude that if class struggle is the motive force of history, it is so only in a specific historical period. This means that before the class struggle—and necessarily after it, since in this world there is no before without an after—one of several factors was and will be the motive force of history. It is not difficult to see that this factor in the history of each human group is the mode of production—the level of productive forces and the pattern of ownership—characteristic of that group. Furthermore, as we have seen, classes themselves, class struggle and their subsequent definition, are the result of the development of the productive forces in conjunction with the pattern of ownership of the means of production. It therefore seems correct to conclude that the level of productive forces, the essential determining element in the content and form of class struggle, is the true and permanent motive force of history.

If we accept this conclusion, then the doubts in our minds are cleared away. Because if on the one hand we can see that the existence of history before the class struggle is guaranteed, and thus avoid for some human groups in our countries—and perhaps in our continent—the sad position of being peoples without any history, then on the other hand we can see that history has continuity, even after the disappearance of class struggle or of classes themselves. And as it was not we who postulated—on a scientific basis—the fact of the disappearance of classes as a historical inevitability, we can feel satisfied at having reached this conclusion which, to a certain extent, re-establishes coherence and at the same time gives to those peoples who, like the people of Cuba, are building socialism, the agreeable certainty that they will not cease to have a history when they complete the process of elimination of the phenomenon of ‘class’ and class struggle within their socio-economic whole. Eternity is not of this world, but man will outlive classes and will continue to produce and make history, since he can never free himself from the burden of his needs, both of mind and of body, which are the basis of the development of the forces of production.

The foregoing, and the reality of our times, allow us to state that the history of one human group or of humanity goes through at least three stages. The first is characterised by a low level of productive forces—of man’s domination over nature; the mode of production is of a rudimentary character, private appropriation of the means of production does not yet exist, there are no classes, nor, consequently, is there any class struggle. In the second stage, the increased level of productive forces leads to private appropriation of the means of production, progressively complicates the mode of production, provokes conflicts of interests within the socio-economic whole in movement, and makes possible the appearance of the phenomenon ‘class’ and hence of class struggle, the social expression of the contradiction in the economic field between the mode of production and private appropriation of the means of production. In the third stage, once a certain level of productive forces is reached, the elimination of private appropriation of the means of production is made possible, and is carried out, together with the elimination of the phenomenon ‘class’, and hence of class struggle; new and hitherto unknown forces in the historical process of the socio-economic whole are then unleashed.

In politico-economic language, the first stage would correspond to the communal agricultural and cattle-raising society, in which the social structure is horizontal, without any state; the third to socialist or communist societies, in which the economy is mainly, if not exclusively, industrial (since agriculture itself becomes a form of industry) and in which the state tends to progressively disappear, or actually disappears, and where the social structure returns to horizontality, at a higher level of productive forces, social relations and appreciation of human values.

At the level of humanity or of part of humanity (human groups within one area, of one or several continents) these three stages (or two of them) can be simultaneous, as is shown as much by the present as by the past. This is a result of the uneven development of human societies, whether caused by internal reasons or by one or more external factors exerting an accelerating or slowing-down influence on their evolution. On the other hand, in the historical process of a given socio-economic whole each of the above- mentioned stages contains, once a certain level of transformation is reached, the seeds of the following stage.

We should also note that in the present phase of the life of humanity, and for a given socio-economic whole, the time sequence of the three characteristic stages is not indispensable. Whatever its level of productive forces and present social structure, a society can pass rapidly through the defined stages appropriate to the concrete local realities (both historical and human) and reach a higher stage of existence. This progress depends on the concrete possibilities of developments of the society’s productive forces and is governed mainly by the nature of the political power ruling the society, that is to say, by the type of state or, if one likes, by the character of the dominant class or classes within the society.

A more detailed analysis would show that the possibility of such a jump in the historical process arises mainly, in the economic field, from the power of the means available to man at the time for dominating nature, and, in the political field, from the new event which has radically changed the face of the world and the development of history, the creation of socialist states.

Thus we see that our peoples have their own history regardless of the stage of their economic development. When they were subjected to imperialist domination, the historical process of each of our peoples (or of the human groups of which they are composed) was subjected to the violent action of an external factor. This action—the impact of imperialism on our societies—could not fail to influence the process of development of the productive forces in our countries and the social structures of our countries, as well as the content and form of our national liberation struggles.

But we also see that in the historical context of the development of these struggles, our peoples have the concrete possibility of going from their present situation of exploitation and underdevelopment to a new stage of their historical process which can lead them to a higher form of economic, social and cultural existence.

The political statement drawn up by the international preparatory committee of this conference, for which we reaffirm our complete support, placed imperialism, by clear and succinct analysis, in its economic context and historical co-ordinates. We will not repeat here what has already been said in the assembly. We will simply state that imperialism can be defined as a worldwide expression of the search for profits and the ever-increasing accumulation of surplus value by monopoly financial capital, centred in two parts of the world; first in Europe, and then in North America. And if we wish to place the fact of imperialism within the general trajectory of the evolution of the transcendental factor which has changed the face of the world, namely capital and the process of its accumulation, we can say that imperialism is partly transplanted from the seas to dry land, partly reorganised, consolidated and adapted to the aim of exploiting the natural and human resources or our peoples. But if we can calmly analyse the imperialist phenomenon, we will not shock anybody by admitting that imperialism—and everything goes to prove that it is in fact the last phase in the evolution of capitalism—has been a historical necessity, a consequence of the impetus given by the productive forces and of the transformations of the means of production in the general context of humanity, considered as one movement, that is to say a necessity like those today of the national liberation of peoples, the destruction of capital and the advent of socialism.

The important thing for our peoples is to know whether imperialism, in its role as capital in action, has fulfilled in our countries its historical mission: the acceleration of the process of development of the productive forces and their transformation in the sense of increasing complexity in the means of production; increasing the differentiation between the classes with the development of the bourgeoisie, and intensifying the class struggle; and appreciably increasing the level of economic, social and cultural life of the peoples. It is also worth examining the influences and effects of imperialist action on the social structures and historical processes of our peoples.

We will not condemn nor justify imperialism here; we will simply state that as much on the economic level as on the social and cultural level, imperialist capital has not remotely fulfilled the historical mission carried out by capital in the countries of accumulation. This means that if, on the one hand, imperialist capital has had, in the great majority of the dominated countries, the simple function of multiplying surplus value, it can be seen on the other hand that the historical capacity of capital (as indestructible accelerator of the process of development of productive forces) depends strictly on its freedom, that is to say on the degree of independence with which it is utilized. We must however recognise that in certain cases imperialist capital or moribund capitalism has had sufficient self-interest, strength and time to increase the level of productive forces (as well as building towns) and to allow a minority of the local population to attain a higher and even privileged standard of living, thus contributing to a process which some would call dialectical, by widening the contradictions within the societies in question. In other, even rarer cases, there has existed the possibility of accumulation of capital, creating the conditions for the development of a local bourgeoisie.

On the question of the effects of imperialist domination on the social structure -and historical process of our peoples, we should first of all examine the general forms of imperialist domination. There are at least two forms: the first is direct domination, by means of a political power made up of people foreign to the dominated people (armed forces, police, administrative agents and settlers); this is generally called classical colonialism or colonialism. The second form is indirect domination, by a political power made up mainly or completely of native agents; this is called neo-colonialism.

In the first case, the social structure of the dominated people, whatever its stage of development, can suffer the following consequences: (a) total destruction, generally accompanied by immediate or gradual elimination of the native population and, consequently, by the substitution of a population from outside; (b) partial destruction, generally accompanied by a greater or lesser influx of population from outside; (c) apparent conservation, conditioned by confining the native society to zones or reserves generally offering no possibilities of living, accompanied by massive implantation of population from outside.

The two latter cases are those which we must consider in the framework of the problematic national liberation, and they are extensively present in Africa. One can say that in either case the influence of imperialism on the historical process of the dominated people produces paralysis, stagnation and even in some cases regression in this process. However this paralysis is not complete. In one section or another of the socio-economic whole in question, noticeable transformations can be expected, caused by the permanent action of some internal (local) factors or by the action of new factors introduced by the colonial domination, such as the introduction of money and the development of urban centres. Among these transformations we should particularly note, in certain cases, the progressive loss of prestige of the ruling native classes or sectors, the forced or voluntary exodus of part of the peasant population to the urban centres, with the consequent development of new social strata; salaried workers, clerks, employees in commerce and the liberal professions, and an instable stratum of unemployed. In the countryside there develops, with very varied intensity and always linked to the urban milieu, a stratum made up of small landowners. In the case of neo-colonialism, whether the majority of the colonised population is of native or foreign origin, the imperialist action takes the form of creating a local bourgeoisie or pseudo-bourgeoisie, controlled by the ruling class of the dominating country.

The transformations in the social structure are not so marked in the lower strata, above all in the countryside, which retains the characteristics of the colonial phase; but the creation of a native pseudo-bourgeoisie which generally develops out of a petty bourgeoisie of bureaucrats and accentuates the differentiation between the social strata and intermediaries in the commercial system (compradores), by strengthening the economic activity of local elements, opens up new perspectives in the social dynamic, mainly by the development of an urban working class, the introduction of private agricultural property and the progressive appearance of an agricultural proletariat. These more or less noticeable transformations of the social structure, produced by a significant increase in the level of productive forces, have a direct influence on the historical process of the socio-economic whole in question. While in classical colonialism this process is paralysed, neo-colonialist domination, by allowing the social dynamic to awaken (conflicts of interest between native social strata or class struggles), creates the illusion that the historical process is returning to its normal evolution. This illusion will be reinforced by the existence of a political power (national state) composed of native elements. In reality it is scarcely even an illusion, since the submission of the local ‘ruling’ class to the ruling class of the dominating country limits or prevents the development of the national productive forces. But in the concrete conditions of the present-day world economy this dependence is fatal and thus the local pseudo-bourgeoisie, however strongly nationalist it may be, cannot effectively fulfill its historical function; it cannot freely direct the development of the productive forces; in brief it cannot be a national bourgeoisie. For as we have seen, the productive forces are the motive force of history, and total freedom of the process of their development is an indispensable condition for their proper functioning.

We therefore see that both in colonialism and in neocolonialism the essential characteristic of imperialist domination remains the same: the negation of the historical process of the dominated people by means of violent usurpation of the freedom of development of the national productive forces. This observation, which identifies the essence of the two apparent forms of imperialist domination, seems to us to be of major importance for the thought and action of liberation movements, both in the course of struggle and after the winning of independence.

On the basis of this, we can state that national liberation is the phenomenon in which a given socio-economic whole rejects the negation of its historical process. In other words, the national liberation of a people is the regaining of the historical personality of that people, its return to history through the destruction of the imperialist domination to which it was subjected.

We have seen that violent usurpation of the freedom of the process of development of the productive forces of the dominated socio-economic whole constitutes the principal and permanent characteristic of imperialist domination, whatever its form. We have also seen that this freedom alone can guarantee the normal development of the historical process of a people. We can therefore conclude that national liberation exists only when the national productive forces have been completely freed from every kind of foreign domination.

It is often said that national liberation is based on the right of every people to freely control its own destiny and that the objective of this liberation is national independence. Although we do not disagree with this vague and subjective way of expressing a complex reality, we prefer to be objective, since for us the basis of national liberation, whatever the formulas adopted on the level of international law, is the inalienable right of every people to have its own history, and the objective of national liberation is to regain this right usurped by imperialism, that is to say, to free the process of development of the national productive forces.

For this reason, in our opinion, any national liberation movement which does not take into consideration this basis and this objective may certainly struggle against imperialism, but will surely not be struggling for national liberation.

This means that, bearing in mind the essential characteristics of the present world economy, as well as experiences already gained in the field of anti-imperialist struggle, the principal aspect of national liberation struggle is the struggle against neo-colonialism. Furthermore, if we accept that national liberation demands a profound mutation in the process of development of the productive forces, we see that this phenomenon of national liberation necessarily corresponds to a revolution. The important thing is to be conscious of the objective and subjective conditions in which this revolution can be made and to know the type or types of struggle most appropriate for its realisation.

We are not going to repeat here that these conditions are favourable in the present phase of the history of humanity; it is sufficient to recall that unfavourable conditions also exist, just as much on the international level as on the internal level of each nation struggling for liberation.

On the international level, it seems to us that the following factors, at least, are unfavourable to national liberation movements: the neo-colonial situation of a great number of states which, having won political independence, are now tending to join up with others already in that situation; the progress made by neo-capitalism, particularly in Europe, where imperialism is adopting preferential investments, encouraging the development of a privileged proletariat and thus lowering the revolutionary level of the working classes; the open or concealed neo-colonial position of some European states which, like Portugal, still have colonies; the so-called policy of ‘aid for undeveloped countries’ adopted by imperialism with the aim of creating or reinforcing native pseudo-bourgeoisies which are necessarily dependent on the international bourgeoisie, and thus obstructing the path of revolution; the claustrophobia and revolutionary timidity which have led some recently independent states whose internal economic and political conditions are favourable to revolution to accept compromises with the enemy or its agents; the growing contradictions between anti-imperialist states; and finally, the threat to world peace posed by the prospect of atomic war on the part of imperialism. All these factors reinforce the action of imperialism against the national liberation movements.

If the repeated interventions and growing aggressiveness of imperialism against the peoples can be interpreted as a sign of desperation faced with the size of the national liberation movements, they can also be explained to a certain extent by the weaknesses produced by these unfavourable factors within the general front of the anti-imperialist struggle.

On the internal level, we believe that the most important weaknesses or unfavourable factors are inherent in the socioeconomic structure and in the tendencies of its evolution under imperialist pressure, or to be more precise in the little or no attention paid to the characteristics of this structure and these tendencies by the national liberation movements in deciding on the strategy of their struggles.

By saying this we do not wish to diminish the importance of other internal factors which are unfavourable to national liberation, such as economic under-development, the consequent social and cultural backwardness of the popular masses, tribalism and other contradictions of lesser importance. It should however be pointed out that the existence of tribes only manifests itself as an important contradiction as a function of opportunistic attitudes, generally on the part of detribalised individuals or groups, within the national liberation movements. Contradictions between classes, even when only embryonic, are of far greater importance than contradictions between tribes.

Although the colonial and neo-colonial situations are identical in essence, and the main aspect of the struggle against imperialism is neo-colonialist, we feel it is vital to distinguish in practice these two situations. In fact the horizontal structure, however it may differ from the native society, and the absence of a political power composed of national elements in the colonial situation make possible the creation of a wide front of unity and struggle, which is vital to the success of the national liberation movement. But this possibility does not remove the need for a rigorous analysis of the native social structure, of the tendencies of its evolution, and for the adoption in practice of appropriate measures for ensuring true national liberation. While recognising that each movement knows best what to do in its own case, one of these measures seems to us indispensable, namely the creation of a firmly united vanguard, conscious of the true meaning and objective of the national liberation struggle which it must lead. This necessity is all the more urgent since we know that with rare exceptions the colonial situation neither permits nor needs the existence of significant vanguard classes (working class conscious of its existence and rural proletariat) which could ensure the vigilance of the popular masses over the evolution of the liberation movement. On the contrary, the generally embryonic character of the working classes and the economic, social and cultural situation of the physical force of most importance in the national liberation struggle—the peasantry—do not allow these two main forces to distinguish true national independence from fictitious political independence. Only a revolutionary vanguard, generally an active minority, can be aware of this distinction from the start and make it known, through the struggle, to the popular masses. This explains the fundamentally political nature of the national liberation struggle and to a certain extent makes the form of struggle important in the final result of the phenomenon of national liberation.

In the neo-colonial situation the more or less vertical structure of the native society and the existence of a political power composed of native elements—national state—already worsen the contradictions within that society and make difficult if not impossible the creation of as wide a front as in the colonial situation. On the one hand the material effects (mainly the nationalisation of cadres and the increased economic initiative of the native elements, particularly in the commercial field) and the psychological effects (pride in the belief of being ruled by one’s own compatriots, exploitation of religious or tribal solidarity between some leaders and a fraction of the masses) together demobilise a considerable part of the nationalist forces. But on the other hand the necessarily repressive nature of the neocolonial state against the national liberation forces, the sharpening of contradictions between classes, the objective permanence of signs and agents of foreign domination (settlers who retain their privileges, armed forces, racial discrimination), the growing poverty of the peasantry and the more or less notorious influence of external factors all contribute towards keeping the flame of nationalism alive, towards progressively raising the consciousness of wide popular sectors and towards reuniting the majority of the population, on the very basis of awareness of neo-colonialist frustration, around the ideal of national liberation. In addition, while the native ruling class becomes progressively more bourgeois, the development of a working class composed of urban workers and agricultural proletarians, all exploited by the indirect domination of imperialism opens up new perspectives for the evolution of national liberation. This working class, whatever the level of its political consciousness (given a certain minimum, namely the awareness of its own needs), seems to constitute the true popular vanguard of the national liberation struggle in the neo-colonial case. However it will not be able to completely fulfil its mission in this struggle (which does not end with the gaining of independence) unless it firmly unites with the other exploited strata, the peasants in general (hired men, sharecroppers, tenants and small farmers) and the nationalist petty bourgeoisie. The creation of this alliance demands the mobilisation and organisation of the nationalist forces within the framework (or by the action) of a strong and well-structured political organisation.

Another important distinction between the colonial and neocolonial situations is in the prospects for the struggle. The colonial situation (in which the nation class fights the repressive forces of the bourgeoisie of the colonising country) can lead, apparently at least, to a nationalist solution (national revolution); the nation gains its independence and theoretically adopts the economic structure which best suits it. The neo-colonial situation (in which the working classes and their allies struggle simultaneously against the imperialist bourgeoisie and the native ruling class) is not resolved by a nationalist solution; it demands the destruction of the capitalist structure implanted in the national territory by imperialism, and correctly postulates a socialist solution.

This distinction arises mainly from the different levels of the productive forces in the two cases and the consequent sharpening of the class struggle.

It would not be difficult to show that in time the distinction becomes scarcely apparent. It is sufficient to recall that in our present historical situation—elimination of imperialism which uses every means to perpetuate its domination over our peoples, and consolidation of socialism throughout a large part of the world—there are only two possible paths for an independent nation: to return to imperialist domination (neo-colonialism, capitalism, state capitalism), or to take the way of socialism. This operation, on which depends the compensation for the effects and sacrifices of the popular masses during the struggle, is considerably influenced by the form of struggle and the degree of revolutionary consciousness of those who lead it. The facts make it unnecessary for us to prove that the essential instrument of imperialist domination is violence. If we accept the principle that the liberation struggle is a revolution and that it does not finish at the moment when the national flag is raised and the national anthem played, we will see that there is not, and cannot be national liberation without the use of liberating violence by the nationalist forces, to answer the criminal violence of the agents of imperialism. Nobody can doubt that, whatever its local characteristics, imperialist domination implies a state of permanent violence against the nationalist forces. There is no people on earth which, having been subjected to the imperialist yoke (colonialist or neo-colonialist), has managed to gain its independence (nominal or effective) without victims. The important thing is to determine which forms of violence have to be used by the national liberation forces in order not only to answer the violence of imperialism but also to ensure through the struggle the final victory of their cause, true national independence. The past and present experiences of various peoples, the present situation of national liberation struggles in the world (especially in Vietnam, the Congo and Zimbabwe) as well as the situation of permanent violence, or at least of contradictions and upheavals, in certain countries which have gained their independence by the so-called peaceful way, show us not only that compromises with imperialism do not work, but also that the normal way of national liberation, imposed on peoples by imperialist repression, is armed struggle.

We do not think we will shock this assembly by stating that the only effective way of definitively fulfilling the aspirations of the peoples, that is to say of attaining national liberation, is by armed struggle. This is the great lesson which the contemporary history of liberation struggle teaches all those who are truly committed to the effort of liberating their peoples.

It is obvious that both the effectiveness of this way and the stability of the situation to which it leads after liberation depend not only on the characteristics of the organisation of the struggle but also on the political and moral awareness of those who, for historical reasons, are capable of being the immediate heirs of the colonial or neo-colonial state. For events have shown that the only social sector capable of being aware of the reality of imperialist domination and of directing the state apparatus inherited from this domination is the native petty bourgeoisie. If we bear in mind the aleatory characteristics and the complexity of the tendencies naturally inherent in the economic situation of this social stratum or class, we will see that this specific inevitability in our situation constitutes one of the weaknesses of the national liberation movement.

The colonial situation, which does not permit the development of a native pseudo-bourgeoisie and in which the popular masses do not generally reach the necessary level of political consciousness before the advent of the phenomenon of national liberation, offers the petty bourgeoisie the historical opportunity of leading the struggle against foreign domination, since by nature of its objective and subjective position (higher standard of living than that of the masses, more frequent contact with the agents of colonialism, and hence more chances of being humiliated, higher level of education and political awareness, etc.) it is the stratum which most rapidly becomes aware of the need to free itself from foreign domination. This historical responsibility is assumed by the sector of the petty bourgeoisie which, in the colonial context, can be called revolutionary, while other sectors retain the doubts characteristic of these classes or ally themselves to colonialism so as to defend, albeit illusorily, their social situation.

The neo-colonial situation, which demands the elimination of the native pseudo-bourgeoisie so that national liberation can be attained, also offers the petty bourgeoisie the chance of playing a role of major and even decisive importance in the struggle for the elimination of foreign domination. But in this case, by virtue of the progress made in the social structure, the function of leading the struggle is shared (to a greater or lesser extent) with the more educated sectors of the working classes and even with some elements of the national pseudo-bourgeoisie who are inspired by patriotic sentiments. The role of the sector of the petty bourgeoisie which participates in leading the struggle is all the more important since it is a fact that in the neo-colonial situation it is the most suitable sector to assume these functions, both because of the economic and cultural limitations of the working masses, and because of the complexes and limitations of an ideological nature which characterise the sector of the national pseudo-bourgeoisie which supports the struggle. In this case it is important to note that the role with which it is entrusted demands from this sector of the petty bourgeoisie a greater revolutionary consciousness, and the capacity for faithfully interpreting the aspirations of the masses in each phase of the struggle and for identifying themselves more and more with the masses.

But however high the degree of revolutionary consciousness of the sector of the petty bourgeoisie called on to fulfill this historical function, it cannot free itself from one objective reality: the petty bourgeoisie, as a service class (that is to say that a class not directly involved in the process of production) does not possess the economic base to guarantee the taking over of power. In fact history has shown that whatever the role—sometimes important—played by individuals coming from the petty bourgeoisie in the process of a revolution, this class has never possessed political control. And it could never possess it, since political control (the state) is based on the economic capacity of the ruling class, and in the conditions of colonial and neo-colonial society this capacity is retained by two entities: imperialist capital and the native working classes.

To retain the power which national liberation puts in its hands, the petty bourgeoisie has only one path: to give free rein to its natural tendencies to become more bourgeois, to permit the development of a bureaucratic and intermediary bourgeoisie in the commercial cycle, in order to transform itself into a national pseudo-bourgeoisie, that is to say in order to negate the revolution and necessarily ally itself with imperialist capital. Now all this corresponds to the neo-colonial situation, that is, to the betrayal of the objectives of national liberation. In order not to betray these objectives, the petty bourgeoisie has only one choice: to strengthen its revolutionary consciousness, to reject the temptations of becoming more bourgeois and the natural concerns of its class mentality, to identify itself with the working classes and not to oppose the normal development of the process of revolution. This means that in order to truly fulfil the role in the national liberation struggle, the revolutionary petty bourgeoisie must be capable of committing suicide as a class in order to be reborn as revolutionary workers, completely identified with the deepest aspirations of the people to which they belong.

This alternative—to betray the revolution or to commit suicide as a class—constitutes the dilemma of the petty bourgeoisie in the general framework of the national liberation struggle. The positive solution in favour of the revolution depends on what Fidel Castro recently correctly called the development of revolutionary consciousness. This dependence necessarily calls our attention to the capacity of the leader of the national liberation struggle to remain faithful to the principles and to the fundamental cause of this struggle. This shows us, to a certain extent, that if national liberation is essentially a political problem, the conditions for its development give it certain characteristics which belong to the sphere of morals.

We will not shout hurrahs or proclaim here our solidarity with this or that people in struggle. Our presence is in itself a cry of condemnation of imperialism and a proof of solidarity with all peoples who want to banish from their country the imperialist yoke, and in particular with the heroic people of Vietnam. But we firmly believe that the best proof we can give of our anti- imperialist position and of our active solidarity with our comrades in this common struggle is to return to our countries, to further develop this struggle and to remain faithful to the principles and objectives of national liberation.

Our wish is that every national liberation movement represented here may be able to repeat in its own country, arms in hand, in unison with its people, the already legendary cry of Cuba:

PATRIA 0 MUERTE, VENCEREMOS!

DEATH TO THE FORCES OF IMPERIALISM!

FREE, PROSPEROUS AND HAPPY COUNTRY FOR EACH OF OUR

PEOPLES!

VENCEREMOS!