The Battle of Waterberg took place on August 11, 1904, in German South-West Africa (Namibia) and triggered the annihilation decree by German military of the Herero people, the indigenous nomadic inhabitants of the area. An estimated 60,000 to 100,000 people perished after the Battle of Waterberg, which marked the beginning of Germany’s extermination campaign that continued until 1908.

The German colonization of South-West Africa began in 1883, two years before the official Partition of Africa, when settlers arrived and expropriated land, cattle, and water rights from local peoples, including the Herero. By 1903, the Herero had ceded over 50,000 square miles of land to the Germans. Some Herero resisted German settler encroachment and engaged in periodic battles with the settlers. In one of the largest of these battles, the Herero–led Samuel Maharere–killed about 100 German soldiers and farmers near the small northern town of Okahandja.

The Okahandja deaths were used by Imperial Germany as a pretext to initiate the military occupation of all of South-West Africa. Fourteen thousand troops were dispatched to the German colony under the leadership of Lieutenant General Adrian Dietrich Lothar von Trotha. This proved to be Germany’s most costly military campaign prior to World War I.

By the time the first German troops under von Trotha arrived, the Herero had moved inland away from German settler areas. They considered their conflict with the Germans to be over and were waiting for them begin a dialogue for peace with Maharero.

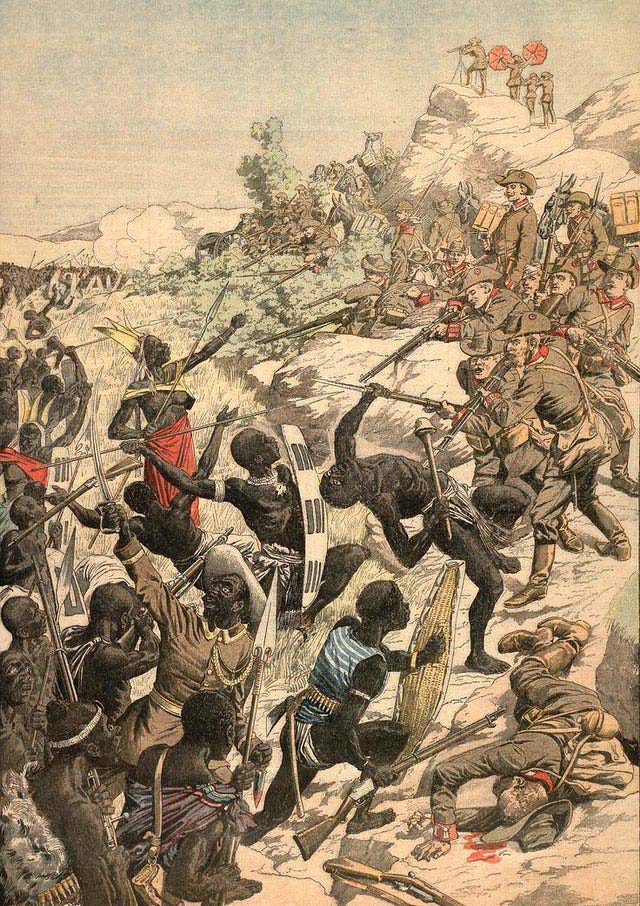

In the spring of 1904, nearly 8,000 Herero had gathered on the Plateau of Waterberg at the last big waterhole before the Omaheke Desert, expecting to engage in land rights negotiation with von Trotha. Instead, on August 11, 1904, German military forces surrounded the Herero and forced them to flee down a dried river bed into the Omaheke Desert. Those not killed by pursuing soldiers perished by thirst.

The German military then constructed a 200-mile fence locking the Herero into the desert. Samuel Maharero successfully led about 1,000 people into present day Botswana, where he remained as an exiled leader until his death in 1923.

Thousands of remaining people were rounded up and placed in concentration camps where they were used as slave labor. They built the prosperous German shipping ports on the Namibian coast such as Luderitz and Swakopmund. By 1908, 45 percent of Herero prisoners had perished, mostly due to exhaustion.

The camps were closed in response to a public backlash in Germany, but the survivors were sold as slaves to German farmers. Estimates suggest that only 15,000 of the estimated 100,000 Herero people in South-West Africa survived the annihilation campaign. Today there are about 250,000 Herero living in Namibia.

Shark Island, an isolated camp near Luderitz was used as an extermination center. An estimated 8,000 Herero perished there, and the camp became the prototype for concentration camps in Nazi Germany three decades later. Research on corpses was conducted on Shark Island by race scientists including Eugen Fischer, who became known as the father of Nazi eugenic policy. General Franz Ritter von Epp (1868-1946), a veteran company commander during the Herero genocide, later mentored Adolf Hitler.

In 2001, Herero living descendants filed a lawsuit in a U.S. court demanding reparations. In 2004, Germany issued an official apology via Heidemarie Wiecaorek-Zeul, the German Development Aid minister. There is no record of reparations ever having been made; however, in 2011, skulls of Herero prisoners taken to Germany for scientific research were returned to Namibia for ceremonial burial.