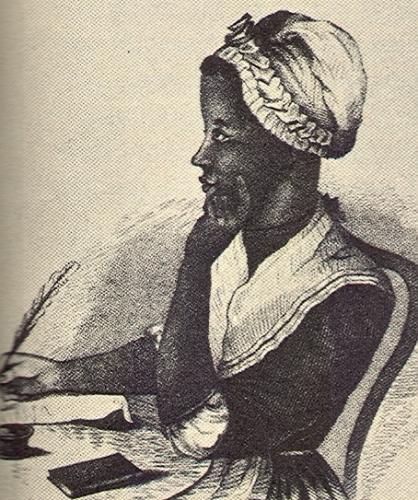

Enslaved in Senegal [in a region that is now in Gambia] at age eight and brought to America on a schooner called the Phillis (for which she was apparently named), was purchased by Susannah and John Wheatley, who soon recognized her intellect and facility with language. Susannah Wheatley taught Phillis to read not only English but some Latin. While yet in her teens, Phillis Wheatley became the first African American woman to publish a book of poetry, and the third woman in the American colonies to do so. That book, Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral, became controversial twice.

Wheatley was alive to defend herself during the first controversy in 1772, when she was summoned before an august group of white Bostonians to prove that she had actually composed her poetry, since common thought of the day denied the possibility of intellectual or aesthetic gifts in Africans. The second time Wheatley and her poetry became controversial was during the 1960s, when her blithe and sometimes glorified treatment of slavery was identified as a hindrance to historical truth and to the Civil Rights Movement. One poem in particular brought Wheatley into a shadowy view: “On Being Brought from Africa to America.” In the poem, she speaks of the “pagan land” of her birth and her “benighted soul” which was saved when was enslaved. Echoing common folklore of the day which held that Africans were the seed of Cain, Wheatley’s poem says, “Remember, Christians, Negroes black as Cain / May be refin’d, and join th’ angelic train.”

Although she remains a controversial figure among African American writers, the significance of her place in American history is uncontested. Phillis Wheatley met or received correspondence from the most famous leaders of the American Revolution, including John Paul Jones, George Washington, Benjamin Franklin, and John Hancock. (Thomas Jefferson was aware but dismissive of Wheatley’s work.) She remains the matriarch of African American literature, and was certainly the most famous African American woman of her day.

Wheatley was emancipated after the publication of her first book of poetry. She married John Peters, a free black grocer who ultimately abandoned her. They had three children, but all three died in infancy, the last just a few hours after Wheatley’s own death at age 31.

Wheatley had completed and tried to publish a second book of poetry by the time she died, but failed to find enough subscribers. Although her work would later be resurrected by abolitionists of the Nineteenth Century, Phillis Wheatley died in a poor dwelling, having fallen from the heights of fame as a poet to the depths of poverty, employed as a seamstress and a common servant.