Decision

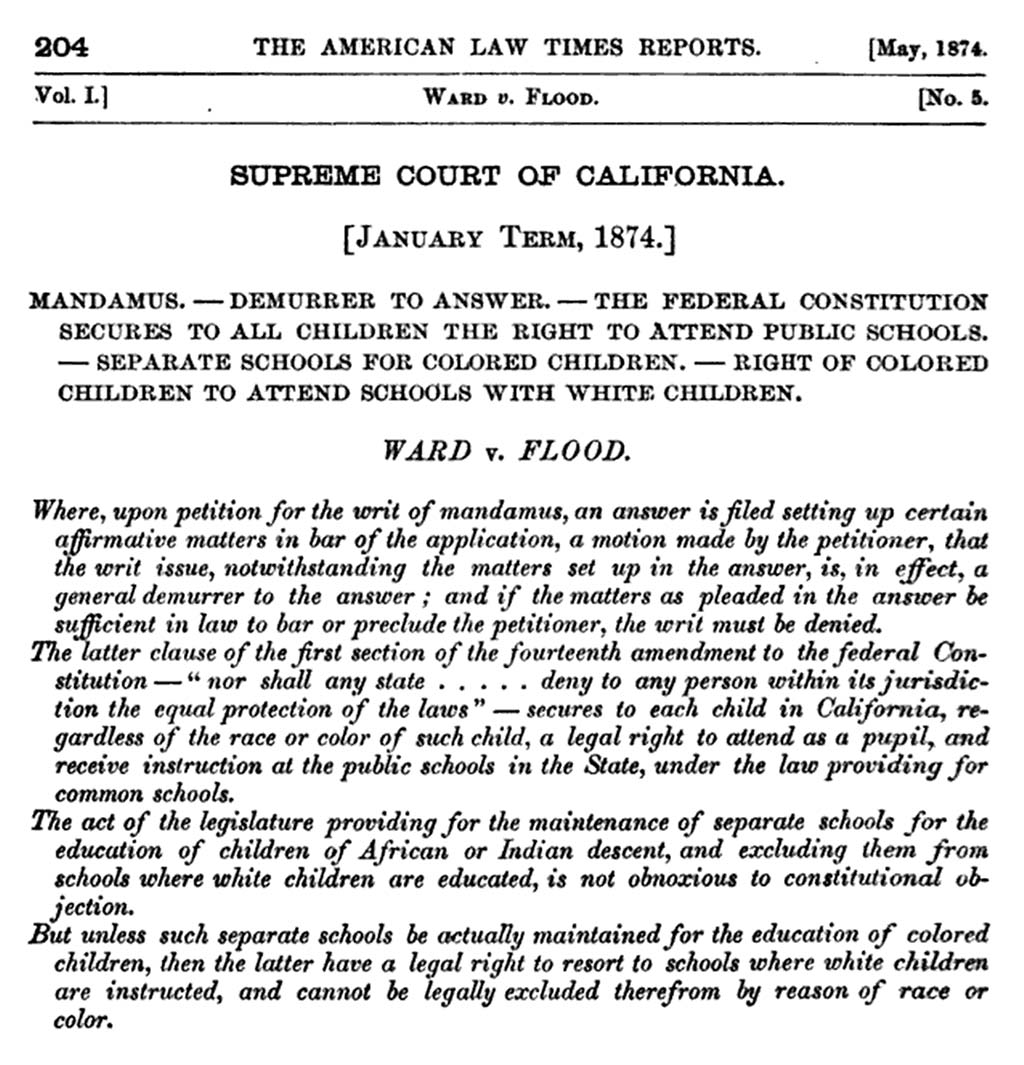

MARY FRANCES WARD, by A. J. WARD, her Guardian, ad litem, v. NOAH F. FLOOD, Principal of the Broadway Grammar School, in the City and County of San Francisco.

SUPREME COURT OF CALIFORNIA

January 1874

The Civil Rights Bill, passed April 9th, 1866, (14 U. S. Statutes at Large, 27,) declares all such emancipated persons born in the United States, to be citizens of the United States.

The Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitution of the United States, adopted July 13-28, 1868, (15 U. S. Statutes at Large, 709,) is in these terms:

ARTICLE XIV, Section 1. All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States, and of the States wherein they reside. No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges and immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty or property, without due process of law, nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction, the equal protection of the laws.

The School Law of California, passed April 4, 1870, (Laws 1869-70, p. 838,) contains the following provisions:

Section 53. Every school, unless otherwise provided by special law, shall be open for the admission of all white children between five and twenty-one years of age residing in that school district, and the Board of Trustees or Board of Education shall have power to admit adults and children not residing in the district, whenever good reasons exist for such exceptions.

Section 56. The education of children of African descent, and Indian children, shall be provided for in separate schools. Upon the written application of at least ten such children to any Board of Trustees, or Board of Education, a separate school shall be established for the education of such children; and the education of a less number may be provided for by the Trustees, in separate schools, or in any other manner.

Section 57. The same laws, rules and regulations, which apply to schools for white children, shall apply to schools for colored.

The Board of Education of the city and county adopted the following regulation which existed at the time when the cause of action arose in this case:

“Section 117. Separate schools. Children of African or Indian descent shall not be admitted into schools for white children; but separate schools shall be provided for them in accordance with the California School Law.” (The People v. The Board of Education of Detroit, 18 Mich. 401.)

The statutes of Michigan provided that “all residents of any school district shall have an equal right to attend any school therein; provided that this shall not prevent the grading of schools according to the intellectual progress of the pupils, to be taught in separate places when expedient.”

Held: That a mandamus would be awarded to compel the admission of a colored pupil into the public schools where white children were taught, although separate schools for colored children had been established.

Note, that the cause of action accrued in April, 1868, and before the Fourteenth Amendment was adopted, on July 21-28, 1868.

This case is therefore only a construction of the then existing laws of Michigan, and is in point in the case in hand, only as showing that “an equal right to attend any school in the district” is not secure by the establishment of colored schools.

State v. Duffy, 7 Nevada, 342; Williams v. School Directors, Wright, 578; Gray v. State, 4 Ohio, 353; Jeffries v. Ankeny, 11 Ohio, 376; Thacker v. Hawk, 11 Ohio, 371; Chalmers v. Stewart, 11 Ohio, 386, 387; Lane v. Baker, 12 Ohio, 237; Stewart v. Southard, 17 Ohio, 402.)

In Clark v. The Board of Directors, etc., 24 Iowa, 267, it was held that under a clause in the Constitution of that State, ordaining that “the Board of Education shall provide for the education of all the youths of the State, through a system of common schools,” the Board of School Directors had no discretionary power to require colored children to attend a separate school. Before the adoption of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments to the Constitution of the United States, this decision would not, probably, have been in point in a case arising under the Constitution of the State of California, which denied to colored children any political status whatsoever. But since those amendments have given the political status of citizens to such children, when either native born or naturalized, the decision in 24 Iowa, ut supra, becomes an authoritative construction of the meaning of the phrase “common schools,” in Article IX, sections two and three of the Constitution of California. “Common schools” does not mean “ordinary” schools. It means public, common to all, in a political sense; and the words common and public are used as equivalent terms in the constitutions and statutes of all the States. Under the decision in 24 Iowa, therefore, no child who is a citizen of California can be excluded, by reason of color or race, from any of the common or public schools of the State.

This is a case which can hardly be argued, any further than its statement alone is an argument. It is admitted now, by the highest masters of thought, even among theologians, that the existence of God himself cannot be proved, nor the duty of children to love and cherish their parents, nor that of general benevolence. But we know that God exists, and that these duties are of imperative obligation. We know that persons of African descent have been degraded by an odious hatred of caste, and that the Constitution of the United States has provided that this social repugnance shall no longer be crystallized into a political disability. This was the object of the Fourteenth Amendment, and its terms are above being the subject of criticism. We know, too, that a State must always have laws equal to its obligations. This was always true as a proposition of municipal law. The world is still ringing with the echoes of its announcement as a proposition of the public law of nations, by the highest tribunal that ever existed in the world, which has just closed its session at Geneva.

Williams and Thornton, for the Defendant.

The Fourteenth Amendment, while it raises the negro to the status of citizenship, confers upon the citizen no new privileges or immunities. It forbids any State to abridge by legislation any of those privileges or immunities secured to any citizen by the second section of the fourth article of the Federal Constitution. They are those great fundamental rights which belong to the citizens of every free and enlightened country, and are so defined in the decisions of all the Courts. (Cooley’s Const. Lim. 15, note 3.)

The right of admission to our public schools is not one of those privileges and immunities. They were unknown, as they now exist, at the time of the adoption of the Federal Constitution; that instrument is silent upon the subject of education, and our public schools are wholly the creation of our own State Constitution and State laws.

The whole system is a beneficent State institution—a grand State charity—and surely those who create the charity have the undoubted right to nominate the beneficiaries of it.

The Fourteenth Amendment provides that “Congress shall have power to enforce, by appropriate legislation, the provisions of this Article.”

Congress has exercised this power, and given us a legislative construction of this article, in accordance with that for which we contend. (U. S. Statutes, Vol. 16, p. 144, Sec. 16; Id. Vol. 14, p. 27, Sec. 1.)

But we find a full answer to this proceeding in the fact that colored children are not excluded from the public schools, for separate schools are provided for them, conducted under the same rules and regulations as those for the white, and in which they enjoy equal, and in some respects superior educational advantages.

So far as they are concerned, no rule of equality is violated—for while they are excluded from the schools for the white, the white are excluded from the school provided for the negro. (Vide Act of April 4, 1870, Secs. 53-56; Swett’s Report, p. 13.)

This Act of the Legislature is constitutional. The Constitution of California on this subject differs materially from most of our State Constitutions. It makes it the duty of the Legislature to “provide for a system of common schools,” thus leaving that body to exercise its own discretion, and to provide such system as it deems wise and just.

The Act of April 4th, 1870, embodies that system; it is the expression of the sovereign will, and is wise, just and politic. (Roberts v. Boston, 5 Cush. 198, 206; The State ex rel., etc. v. Cincinnati, 19 O. 178, 197; Van Camp v. Board of Education, 9 O. State, 406, 414; Westchester & Phil. R. R. v. Miles, 55 Penn. 212; People, etc., v. Board of Education, 18 Mich. 400, 412; State of Nev. ex rel., etc. v. Duffy, 7 Nevada, 342; Clark v. Board of Directors, 24 Iowa, 272.)

Independent of all such considerations, under the police power of the State, the Legislature would have the right, by way of classification, to provide separate schools for the white and black, confining each to its appointed sphere.

This power is most comprehensive. It is inherent in every state, and inalienable. It exerts itself upon persons and property, whenever the safety and welfare of society is endangered. It is exercised for the general comfort, health and prosperity of the people, and for the preservation of the morality, peace and dignity of the commonwealth. (Cooley’s Con. Lim. 572, 574, 576, note 2, 33, note 4.)

Confining colored children to schools specially organized for them, does not impair or abridge any right, conceding that the right exists; it is a simple regulation of rights, with a view to the most convenient and beneficial enjoyment of them by all, and deprives no one of what is justly his own. (Cooley’s Con. Lim. 596-7.)

By the Court, WALLACE, C. J.:

This is an application made to this Court for a writ of mandamus directing the defendant to receive the petitioner as a scholar in the school of which he is the principal. The petition for the writ is as follows:

Harriet A. Ward, being sworn, says: “I am the mother of Mary Frances Ward, who is under the age of fourteen years—namely, of the age of between eleven and twelve years. I am the wife of A. J. Ward, and by that marriage the mother of said Mary Frances Ward. We are all of African descent, colored citizens of the United States and of the State of California, and at present, and continuously for thirteen years now last past, residents of the city and county of San Francisco, and for six months last past, and now, residing at No. 1,006 Pacific street, in the city and county of San Francisco. The city and county of San Francisco is not now, nor for the year last past has been divided into school districts; but by law, and also by the custom adopted and established by the Board of Education of said city and county, pupils residing therein have a right to be received as such at the public school nearest their residence, in case such school is not full, and they have made sufficient progress to be received therein.

“The nearest public school to our said residence in said city and county for six months now last past, and now, is the so-called Broadway Grammar School, on Broadway street, in said city and county, between Powell and Mason streets; a public school under the control of the Board of Education of said city and county, sustained by taxes raised in said city and county for the support of public schools therein, and at the time the application hereinafter mentioned was made, was, and ever since then has been, and is now, in charge of Noah F. Flood as Principal thereof, appointed thereto by, and holding office as such under the said Board of Education.

“On or about the 1st day of July, A. D. 1872, by the consent and direction of my said husband, I took the said Mary Frances Ward with me to the said Broadway Grammar School, the same being in session, and there found the said Noah F. Flood, then and there being such Principal of said school, and then and there as such being the proper and only person to whom to make application for the admission of pupils to the same, and presented her to him, as a pupil asking to be admitted as such to said school. The said school then and there was not full, nor was there any good or lawful reason why the said Mary Frances Ward should not be received therein as such pupil, as aforesaid. But the said Noah F. Flood, instead of making inquiries respecting the said Mary Frances Ward, her residence, citizenship, or in any other respect, or examining her as to her proficiency, at once politely, but firmly and definitively declined to entertain the said application, or to admit the said Mary Frances Ward as such pupil, assigning, as the only reason for such action and refusal, the fact that she was a colored person, and that said Board of Education had established and assigned separate schools for such colored persons, and that he was sorry to be compelled for that reason to adopt that course of action on his part. And I aver that the reason so assigned was true in fact, and was in truth and fact the only reason existing for such action and refusal of the said Noah F. Flood.

“The said Broadway Grammar School was then and is now of the description called a graded school, which signifies that the pupils in it are classified into several distinct grades, according to the instruction which they may respectively require; those of the lowest grade receiving instructions nearly of a primary character; and those of the highest grade receiving instruction of a somewhat thorough character in arithmetic, grammar, and other studies. The said Mary Frances Ward, at the time of said application, had already received sufficient instruction to enable her to enter the lowest grade of said grammar school, but not the highest grade. “Harriet A. Ward.”

The answer of the defendant is as follows:

“Now comes Noah F. Flood, and for his answer in the above entitled action or proceeding, admits that he is and was on or about the 1st day of July, 1872, the Principal of the Broadway Grammar School, in the city and county of San Francisco; admits that Harriet A. Ward, in said action or proceeding mentioned, is the mother of Mary Frances Ward, a minor under the age of fourteen years, and that she is the wife of A. J. Ward; admits that petitioner and her said mother and father are of African descent, and colored citizens of the United States, and admits their residence as stated in the affidavit of Harriet A. Ward in said action or proceeding; admits that the said city and county of San Francisco is not now, nor for the year last past has been divided into school districts; and admits that by law, and also by the custom adopted and established by the Board of Education of said city and county, white pupils residing therein have a right to be received as such at the public school nearest their residence, in case such school is not full, and they have made sufficient progress to be received therein, but denies that children of African descent have a right to be admitted into any public school other than those separately organized and provided for them.

“Further answering, said defendant admits that the nearest public school to the residence of petitioner has been for six months last past, and now is, the said Broadway Grammar School; and admits that the same is a public school under the control of the Board of Education of said city and county, sustained by taxes raised in said city and county for the support of public schools therein, and was on or about the 1st day of July, 1872, and ever since has been, and now is, in charge of this defendant, as Principal thereof, appointed thereto by, and holding office as such under the said Board of Education.

“He admits that on or about the 1st day of July, 1872, the said Harriet A. Ward, by the consent and direction of her said husband, took the petitioner with her to the said Broadway Grammar School, and that the same was then in session; that said Harriet then and there presented the said petitioner to this defendant as a pupil asking to be admitted as such to said school, this defendant then and there being such Principal as aforesaid. He admits that said school was not then and there full, but denies that there was no good or lawful reason why said petitioner should not be received in said school as said pupil as aforesaid, and denies that he had any right or authority to admit her as such pupil, or that she had any right to be admitted as such pupil; but on the contrary, avers that there was a good and sufficient reason in this, that he was appointed as such Principal by the said Board of Education, and in refusing to receive the petitioner as a pupil, he acted under and in accordance with the rules and regulations adopted and prescribed by the said Board, one of which is as follows:

‘Section 117. Separate Schools.—Children of African or Indian descent shall not be admitted into schools for white children, but separate schools shall be provided for them in accordance with the California School Law.’

“And this defendant avers that in accordance with said rule and the Act of the Legislature therein referred to, entitled ‘an Act to amend an Act to provide for a system of common schools,’ approved April 4th, 1870, two separate schools were and are provided for colored children, with able and efficient teachers, and which afford equal advantages and are conducted under the same rules and regulations as those provided for the education of white children.

“Further answering, defendant admits that the said Broadway Grammar School was then and is now of the description called a graded school, which signifies that the pupils in it are classified into distinct grades, according to the instruction which they may respectively require; but this defendant avers that the lowest grade in said Grammar school then was and now is the sixth grade, into which the petitioner had not received sufficient instruction to enable her to enter; and further avers that the said Mary Frances Ward, was, prior to and at the time of her said application, and now is a member of and pupil in a school provided for colored children or children of African descent, under the said Act of the Legislature of the State of California, and in the seventh grade of said school.

“And this defendant further avers that the said Mary Frances, in applying for admission into the said Broadway Grammar School, did not present to him as the Principal thereof, any certificate of transfer, as required by the said rules and regulations as adopted by the said Board of Education, one of which rules is as follows:

“‘Section 134. Transfers—Pupils desiring to be transferred from one school to another shall apply to their principal for a certificate, which shall state their name, age, grade, scholarship, deportment, residence and cause of transfer.’

“And now, having fully answered, the said defendant asks that the prayer of petitioner be denied, and that said defendant be hence dismissed, with judgment for his costs in this proceeding incurred.”

The case was submitted for decision upon these pleadings of the respective parties.

1. The motion that the writ issue, notwithstanding the matters alleged in the answer of the defendant, amounts to a general demurrer to the answer. It necessarily assumes that the matters set up in the answer, though true in point of fact, do not in law amount to a defense against the application for the writ. It is averred in the petition, and admitted in the answer, that the Broadway Grammar School, into which the petitioner seeks to be admitted as a pupil, is a graded school—that is to say, a school in which the pupils are classified into several distinct grades, “according to the instruction which they may respectively require,” and the answer thereupon avers “that the lowest grade in said Grammar School then was, and now is, the sixth grade, into which the petitioner had not received sufficient instruction to enable her to enter.” It being, therefore, necessarily admitted for the purposes of this motion, that the attainments of the petitioner, in point of learning, were not sufficient to entitle her to be admitted in any class, even the lowest in the school, it would hardly require an argument to show that the defendant, as Principal of the school, correctly denied her application to be received as a pupil. It is claimed for the petitioner, however, that the refusal of the defendant not having been placed on that ground, but on the sole ground that the petitioner was a colored person, the defendant cannot now be permitted to set up the fact that she was not sufficiently advanced in learning to entitle her to be admitted.

There is no doubt that if a party, upon tender or demand made, or other proceeding en pais, had put his refusal upon some particular omission or defect in the proceedings of his adversary, he will not afterwards be permitted, in support of such refusal, to allege a new or additional defect or insufficiency in those proceedings, especially if such defect or insufficiency be of such a character as that it might have been cured if it had been pointed out or relied upon at the time. This is the ordinary and general rule, and it proceeds upon the idea that, having specially designated one or more supposed insufficiencies, the party thereby waives and abandons all others.

But it is obvious that this rule can have no just application to the case now under consideration. If the law, under the circumstances actually appearing in the record before us, forbade the respondent, as the Principal of the school, to admit the petitioner as a pupil therein, the circumstance that the respondent put his refusal on an untenable ground ought not, in this proceeding, to preclude an examination into the very right of the case. The claim of the petitioner to be admitted, and the corresponding duty of the defendant to admit her as a pupil, are governed by law; and if it appear, as it does unquestionably appear, upon the record before us, that she did not possess the acquirements, in point of learning, sufficient to entitle her, whatever her color, to be admitted to any class in the school, even the lowest, then the respondent must be considered to have correctly refused to entertain her application for admission, and the legal sufficiency of the particular reason assigned by him for such refusal becomes wholly immaterial.

The writ of mandamus is issued to compel the admission of a party to the enjoyment of a substantial right, from which he is unlawfully precluded; and it is necessary that the record should manifest the right claimed, as well as the unlawful preclusion of the petitioner from the enjoyment of that right. Failing in either of these respects, the writ must be denied, for we know of no principle upon which we ought to compel the defendant to entertain the application of the petitioner here, when it appears to us by the record that, should he do so, it will then become his plain duty to again decline to admit her. Upon this view, the application for the writ must fail.

2. But we do not intend to put the decision of the case upon this point alone. We will, therefore, assume for this purpose, that the petitioner was sufficiently advanced in her studies to entitle her to enter some one of the classes of this school; and further, that upon her application for admission as a pupil, she presented the certificate required by the 134th rule of the Board, and also, that the only ground upon which she was denied admission to the school was that she was a child of African descent. These assumptions lead us to inquire whether, under the circumstances appearing, the respondent is justified by law in refusing to admit her. We say under the circumstances appearing, because it is shown by the record that in San Francisco separate schools are not only authorized by law, but are in fact maintained for the education of colored children, “with able and efficient teachers, and which afford equal advantages and are conducted under the same rules and regulations as those provided for the education of white children;” and because it also appears that the petitioner, at the time when she made application to be admitted into the Broadway Grammar School, was a pupil in attendance upon another public school conducted in San Francisco for the education of children of her color, which school, like the Broadway Grammar School, was a graded school, she being a pupil of the seventh grade or class therein. Recurring then to the inquiry whether the refusal of the respondent to admit the petitioner to the school under his charge is justified by the law, it will be seen that the statute of the State (Acts 1869-70, Sec. 56), enacts in terms that “the education of children of African descent, and Indian children, shall be provided for in separate schools,” and if the statute be itself free from objection of a constitutional character, it is evidently a sufficient authority for the one hundred and seventeenth rule of the Board already recited, and in this view the respondent was not only justified in excluding the petitioner from the school in his charge, but in the face of the statute and the rule referred to, he had no discretion to admit her as a pupil therein. It is not claimed by the learned counsel for the petitioner, as we understand him, that the statute in question is forbidden by the Constitution of the State. The argument is that the exclusion of the petitioner from this particular school is contrary to the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments of the Federal Constitution lately adopted. We are, however, unable to perceive in what way it is to be maintained that the State law or the action of the respondent thereunder are in contravention of the Thirteenth Amendment referred to, by which Amendment slavery and involuntary servitude are forbidden. It would seem, indeed, too plain to require argument, that the mere exclusion of the petitioner from this particular school, does not assume to remit her to a condition of slavery or involuntary servitude, in the sense of the Constitution, or in any sense at all; or that there is any—even the slightest—relation between the case here and the prohibition contained in the Amendment referred to.

Nor is it perceived that the State law in question, in obedience to which the respondent proceeded, is obnoxious to those provisions of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Federal Constitution securing the privileges and immunities of citizens of the United States, and protecting all persons against the deprivation of life, liberty or property, without due process of law. That Amendment, so far as claimed to be material to the question, is as follows: “No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges and immunities of citizens of the United States. Nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty or property, without due process of law, nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.”

It will indeed be readily conceded that the privilege accorded to the youth of the State, by the law of the State, of attending the public schools maintained at the expense of the State, is not a privilege or immunity appertaining to a citizen of the United States as such; and it necessarily follows, therefore, that no person can lawfully demand admission as a pupil in any such school because of the mere status of citizenship; and it is perhaps hardly necessary to add that assuredly no person can be said to have been deprived of either life, liberty or property, because denied the right to attend as a pupil at such schools, however obviously insufficient and untenable be the ground upon which the exclusion is put.

The last clause of so much of the Amendment as has been recited, however, forbids the State to “deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws,” and it remains to inquire if the statute of the State, providing for a system of common schools, in so far as it directs that schools shall be maintained for the education of colored children separate from those provided for the education of white children, be obnoxious to this portion of the Federal Constitution.

The opportunity of instruction at public schools is afforded the youth of the State by the statute of the State, enacted in obedience to the special command of the Constitution of the State, directing that the Legislature shall provide for a system of common schools, by which a school shall be kept up and supported in each district, at least three months in every year, etc. (Art. 19, Sec. 3.) The advantage or benefit thereby vouchsafed to each child, of attending a public school is, therefore, one derived and secured to it under the highest sanction of positive law. It is, therefore, a right—a legal right—as distinctively so as the vested right in property owned is a legal right, and as such it is protected, and entitled to be protected by all the guarantees by which other legal rights are protected and secured to the possessor.

The clause of the Fourteenth Amendment referred to did not create any new or substantive legal right, or add to or enlarge the general classification of rights of persons or things existing in any State under the laws thereof. It, however, operated upon them as it found them already established, and it declared in substance that, such as they were in each State, they should be held and enjoyed alike by all persons within its jurisdiction. The protection of law is indeed inseparable from the assumed existence of a recognized legal right, through the vindication of which the protection is to operate. To declare, then, that each person within the jurisdiction of the State shall enjoy the equal protection of its laws, is necessarily to declare that the measure of legal rights within the State shall be equal and uniform, and the same for all persons found therein—according to the respective condition of each—each child as all other children—each adult person as all other adult persons. Under the laws of California children or persons between the ages of five and twenty-one years are entitled to receive instruction at the public schools, and the education thus afforded them is a measure of the protection afforded by law to persons of that condition.

The education of youth is emphatically their protection. Ignorance, the lack of mental and moral culture in earlier life, is the recognized parent of vice and crime in after years. Thus it is the acknowledged duty of the parent or guardian, as part of the measure of protection which he owes to the child or ward, to afford him at least a reasonable opportunity for the improvement of his mind and the elevation of his moral condition, and, of this duty, the law took cognizance long before the now recognized interest of society and of the body politic in the education of its members had prompted its embarkation upon a general system of education of youth. So a ward in chancery, as being entitled to the protection of the Court, was always entitled to be educated under its direction as constituting a most important part of that protection. The public law of the State—both the Constitution and Statute—having established public schools for educational purposes, to be maintained by public authority and at public expense, the youth of the State are thereby become pro hac vice the wards of the State, and under the operations of the constitutional amendment referred to, equally entitled to be educated at the public expense. It would, therefore, not be competent to the Legislature, while providing a system of education for the youth of the State, to exclude the petitioner and those of her race from its benefits, merely because of their African descent, and to have so excluded her would have been to deny to her the equal protection of the laws within the intent and meaning of the Constitution.

But we do not find in the Act of April, 1870, providing for a system of common schools, which is substantially repeated in the Political Code now in force, any legislative attempt in this direction; nor do we discover that the statute is, in any of its provisions, obnoxious to objections of a constitutional character. It provides in substance that schools shall be kept open for the admission of white children, and that the education of children of African descent must be provided for in separate schools.

In short, the policy of separation of the races for educational purposes is adopted by the legislative department, and it is in this mere policy that the counsel for the petitioner professes to discern “an odious distinction of cast, founded on a deep-rooted prejudice in public opinion.” But it is hardly necessary to remind counsel that we cannot deal here with such matters, and that our duties lie wholly within the much narrower range of determining whether this statute, in whatever motive it originated, denies to the petitioner, in a constitutional sense, the equal protection of the laws; and in the circumstances that the races are separated in the public schools, there is certainly to be found no violation of the constitutional rights of the one race more than of the other, and we see none of either, for each, though separated from the other, is to be educated upon equal terms with that other, and both at the common public expense. A question similar to this came before the Supreme Judicial Court of the State of Massachusetts in 1849 (Roberts v. The City of Boston, 5 Cush. 198), and was determined by the Court in accordance with the views just expressed by us. That was an action on the case brought by a colored child against the city to recover damages claimed by reason of her exclusion from a public school as a pupil. It appeared that primary schools to the number of about one hundred and sixty were maintained for the instruction of children of both sexes between five and seven years of age, and that of these schools two were appropriated to the exclusive instruction of colored children, and the residue to the exclusive instruction of white children. It also appeared that the plaintiff had been excluded from the primary school nearest her father’s residence, which was a school devoted exclusively to the instruction of white children, and that the school appropriated to the education of colored children nearest her father’s residence was about a fifth of a mile more distant therefrom than was the school from which she had been excluded. The Constitution of the State of Massachusetts contained the following clauses, which were relied upon by the counsel for the plaintiff to show that the separation of colored from white children for educational purposes was not justified by law. (Part 1, Art. 1:) “All men are born free and equal, and have certain natural, essential and inalienable rights; among which may be reckoned the right of enjoying and defending their lives and liberties, that of acquiring, possessing and protecting property; in fine, that of seeking and obtaining their safety and happiness. Art. 6: No man nor corporation or association of men, have any other title to obtain advantages or particular and exclusive privileges distinct from those of the community, than what arise from consideration of services rendered to the public.” * * *

It will be seen that the language of the Massachusetts Constitution prohibiting “particular and exclusive privileges,” was fully as significant, to say the least, in its bearing on the general question in hand as is that of the Fourteenth Amendment of the Federal Constitution, securing “the equal protection of the laws.”

The argument of the counsel for the plaintiff in the Massachusetts case, much like that of the counsel for the petitioner here, was that the separation of the races for educational purposes, “is the occasion of inconveniences to colored children, to which they would not be exposed if they had access to the nearest public schools; it inflicts upon them the stigma of caste; and although the matters taught in the two schools may be precisely the same, a school exclusively devoted to one class must differ essentially, in its spirit and character, from that public school known to the law, where all classes meet together in equality.”

The opinion of the Court, delivered by Mr. Chief Justice Shaw, maintained the rightful authority of the school committee, to separate the colored children from the white children in the public schools of the city of Boston, and in the course of the opinion, the learned Chief Justice remarked as follows: “It will be considered that this is a question of power, or of the legal authority of the committee intrusted by the city with this department of public instruction; because if they have the legal authority, the expediency of exercising it in any particular way is exclusively with them. The great principle advanced by the learned and eloquent advocate of the plaintiff, is that by the Constitution and laws of Massachusetts, all persons, without distinction of age or sex, birth or color, origin or condition, are equal before the law. This, as a broad general principle, such as ought to appear in a declaration of rights, is perfectly sound; it is not only expressed in terms, but pervades and animates the whole spirit of our Constitution of free government. But when this great principle comes to be applied to the actual and various conditions of persons in society, it will not warrant the assertion that men and women are legally clothed with the same civil and political powers, and that children and adults are legally to have the same functions and be subject to the same treatment; but only that the rights of all, as they are settled and regulated by law, are equally entitled to the paternal consideration and protection of the law, for their maintenance and security. What those rights are, to which individuals in the infinite variety of circumstances by which they are surrounded in society, are entitled, must depend on laws adapted to their respective relations and conditions.

“Conceding, therefore, in the fullest manner, that colored persons, the descendants of Africans, are entitled by law, in this commonwealth, to equal rights, constitutional and political, civil and social, the question then arises whether the regulation in question, which provide separate schools for colored children, is a violation of any of these rights.

“Legal rights must, after all, depend upon the provisions of law; certainly all those rights of individuals which can be asserted and maintained in any judicial tribunal. The proper province of a declaration of rights and constitution of government, after directing its form, regulating its organization and the distribution of its powers, is to declare great principles and fundamental truths, to influence and direct the judgment and conscience of legislators in making laws, rather than to limit and control them, by directing what precise laws they shall make. The provision that it shall be the duty of legislatures and magistrates to cherish the interest of literature and the sciences, especially the University of Cambridge, public schools and grammar schools in the towns, is precisely of this character. Had the Legislature failed to comply with this injunction, and neglected to provide public schools in the towns; or should they so far fail in their duty as to repeal all laws on the subject, and leave all education to depend on private means, strong and explicit as the direction of the Constitution is, it would afford no remedy or redress to the thousands of the rising generation, who now depend on these schools to afford them a most valuable education, and an introduction to useful life. * * * * The power of general superintendence vests a plenary authority in the committee to arrange, classify and distribute pupils, in such a manner as they think best adapted to their general proficiency and welfare. If it is thought expedient to provide for very young children, it may be that such schools may be kept exclusively by female teachers, quite adequate to their instruction, and yet whose services may be obtained at a cost much lower than that of more highly qualified male instructors. So, if they should judge it expedient to have a grade of schools for children from seven to ten, and another for those from ten to fourteen, it would seem to be within their authority to establish such schools. So, to separate male and female pupils into different schools. It has been found necessary, that is to say, highly expedient, at times, to establish special schools for poor and neglected children, who have passed the age of seven, and have become too old to attend the primary school, and yet have not acquired the rudiments of learning to enable them to enter the ordinary schools. If a class of youth, of one or both sexes, is found in that condition, and it is expedient to organize them into a separate school, to receive the special training adapted to their condition, it seems to be within the power of the superintending committee to provide for the organization of such special school. * * * In the absence of special legislation on this subject, the law has vested the power in the committee to regulate the system of distribution and classification; and when this power is reasonably exercised, without being abused or perverted by colorable pretences, the decision of the committee must be deemed conclusive. The committee, apparently upon great deliberation, have come to the conclusion that the good of both classes of schools will be best promoted by maintaining the separate primary schools for colored and for white children, and we can perceive no ground to doubt that this is the honest result of their experience and judgment. It is urged that this maintenance of separate schools tends to deepen and perpetuate the odious distinction of caste, founded on a deep-rooted prejudice in public opinion. This prejudice, if it exists, is not created by law, and probably cannot be changed by law. Whether this distinction and prejudice, existing in the opinion and feelings of the community, would not be as effectually fostered by compelling colored and white children to associate together in the same schools, may well be doubted; at all events, it is a fair and proper question for the committee to consider and decide upon, having in view the best interests of both classes of children placed under their superintendence; and we cannot say that their decision upon it is not founded on just grounds of reason and experience, and in the results of a discriminating and honest judgment.”

We concur in these views, and they are decisive of the present controversy. In order to prevent possible misapprehension, however, we think proper to add that in our opinion, and as the result of the views here announced, the exclusion of colored children from schools where white children attend as pupils, cannot be supported, except under the conditions appearing in the present case; that is, except where separate schools are actually maintained for the education of colored children; and that, unless such separate schools be in fact maintained, all children of the school district, whether white or colored, have an equal right to become pupils at any common school organized under the laws of the State, and have a right to registration and admission as pupils in the order of their registration, pursuant to the provisions of subdivision fourteen of section 1,617 of the Political Code.

Writ of mandamus denied.

McKINSTRY, J., concurring specially:

I concur in the judgment on the ground first considered in the opinion of the Chief Justice.

Mr. Justice RHODES did not express an opinion.