In the five years following the Civil War, the U.S. Congress passed and the states ratified the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments to the Constitution. These amendments permanently ended slavery and granted African Americans access to civil rights and suffrage as citizens of the United States. Although these changes were designed to assist the formerly enslaved, violent opposition arose from white ex-Confederates who opposed them. That violence led Congress to empower President Ulysses S. Grant to use military force to protect African Americans.

The Enforcement Act was, in fact, three separate laws that Congress passed between 1870 and 1871. These acts were specifically designed to protect African Americans’ right to vote, to hold office, to serve on juries, and to receive equal protection of laws. The three bills passed by Congress were the Enforcement Act of 1870, the Enforcement Act of 1871, and the Ku Klux Klan Act.

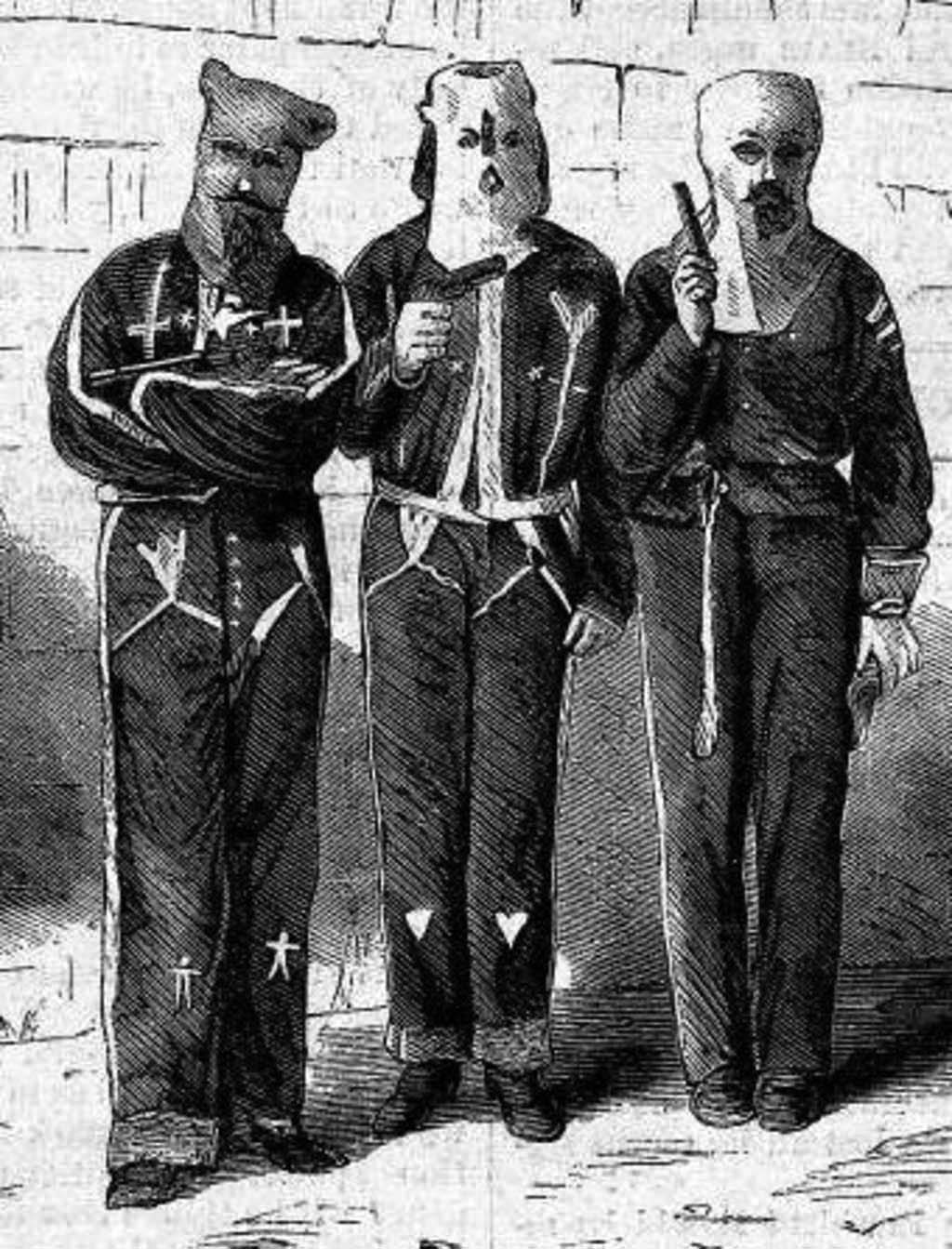

In May 1870, Congress enacted the Enforcement Act to restrict the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) and other terrorist organizations from harassing and torturing African Americans. The Act prohibited individuals from assembling or disguising themselves with intentions to violate African Americans’ constitutional rights. The Act outlined the penalties for those who chose to interfere with a citizen’s right to vote. In December of 1870, Indiana Republican Senator Oliver H.P.T. Morton introduced a resolution that required the President to convey information in regard to incidents of resistance against the full execution of the United States laws. When Congress enacted adopted Morton’s resolution, President Ulysses Grant was now obligated to report to Congress incidents of anti-black violence in the Southern states.

In response to the first report, a committee of the Senate, chaired by Senator Henry Wilson of Massachusetts, opened an investigation of acts of violence against the freedpeople across the South. The numerous incidents led to the enactment of the second Enforcement act, which passed in February 1871. The second Enforcement Act amended the first Enforcement Act by adding more severe punishments to the revisions. This act was best enforced by the United States Government.

Two months later in April 1871, Congress passed the third and final measure, known as the Ku Klux Klan Act. This Act outlawed terrorist conspiracies by all racist vigilantes including but not limited to the Ku Klux Klan. It allowed the President to suspend the writ of Habeas Corpus in regions prone to terrorist activities.

Overall, the acts undermined the organized violence of the Ku Klux Klan. The Acts, unfortunately, did not stop all violent resistance to African American participation in voting across the South. That violence helped overthrow Reconstruction governments in all but three ex-Confederate states by the end of President Grant’s second term. The U.S. Supreme Court in two rulings also undermined the Acts. In United States v. Reese et al. 1876 and the United States v. Cruikshank 1876 opponents of the Enforcement Acts challenged their constitutionality. The Court agreed with the plaintiffs and concluded that voting rights are best-regulated by state authorities without federal intervention.