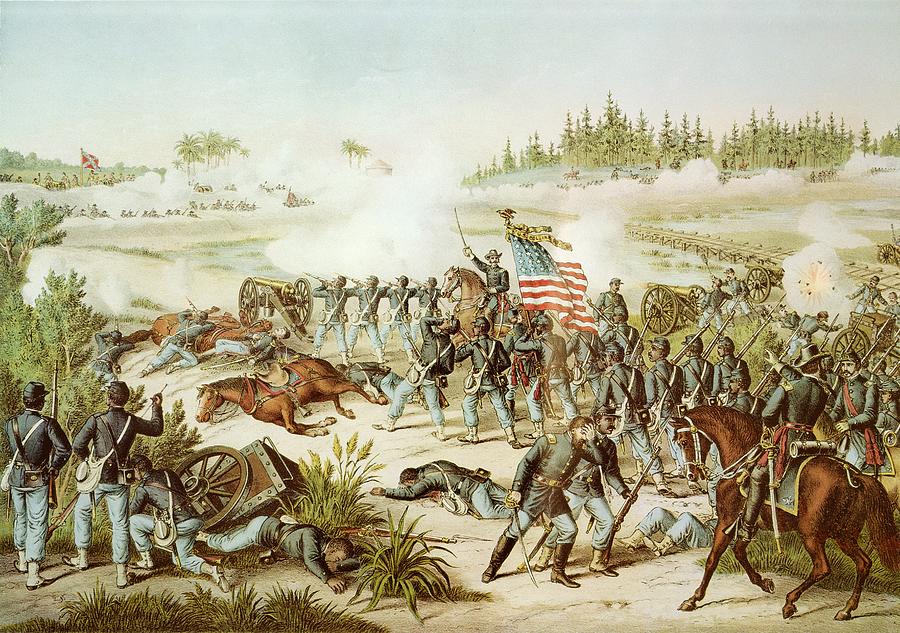

On February 20, 1864, the Battle of Olustee, also referred to as the Battle of Ocean Pond, was fought in Baker County, Florida. Notably, it was a major battle fought by Black Union Army troops as well as the final Civil War battle in Florida, as this decisive Confederate victory secured Southern control of Florida until the end of the War.

Weeks earlier, Union General Quincy Gilmore, commander of the Department of the South at South Carolina, organized an invasion into Florida. His main objectives included expanding Union holdings, intercepting Confederate supply routes, and attracting black recruits. Leading the 5,500-man expedition was Truman Seymour, an experienced Brigadier General. Under his charge, the Union troops advanced into Jacksonville on February 7. From there, cavalry raiders pushed inland, seizing Confederate artillery and slowly extending the Union’s reach into Lake City and Gainesville.

Accompanying the Union troops, John Hay, secretary to Abraham Lincoln, also entered Florida in pursuit of a different, non-military objective: issuing loyalty oaths to residents. Lincoln’s “Ten Percent Plan” for Reconstruction dictated that a Republican state government could be formed once 10% of the prewar voting population had pledged an oath of loyalty to the Union. With the 1864 Republican Party convention looming, Hay hoped to form the new state government and expand the Republican voting delegation in time for the election.

Meanwhile, hoping to capitalize on the successful raids, Seymour led the infantry inland towards Lake City and arrived near Olustee Station on the morning of February 20. Shortly after, Confederate General Joseph Finegan sent his infantry brigade to counter the advance, and a series of skirmishes ensued. Both Finegan and Seymour committed their troops sparingly, engaging only a few units simultaneously, but each side gradually added reinforcements as the battle intensified. By late afternoon, both forces had around 5,000 troops engaged. Union front lines attempted to attack but were quickly overpowered by Confederate cannon fire; as a result, Union forces continued to decline but held their ground after receiving word that Confederate supplies were dwindling. However, the arrival of more ammunition and the resulting Confederate rejuvenation soon spelled defeat for Seymour and his forces.

By nightfall, the Union troops had started their retreat to Jacksonville. Finegan attempted a final attack on the rear element of the Union force, but black soldiers from the 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry Regiment and the 35th United States Colored Troops suppressed these efforts. In retaliation, Finegan decided to forego further pursuit of Union troops and instead killed the remaining wounded and captured black soldiers. In all, Union casualties totaled 203 dead, 1,152 wounded, and 506 missing, a loss of about 34 percent. Confederate casualties were lower at 19 percent, or 946 men total.

The battle’s results produced different responses across the nation. In the Confederacy, the battle significantly boosted morale, and Southern newspapers considered it a decisive victory some believed would lead to an eventual triumph over the Union. For the Union, while the political objective of establishing a Republican government in Florida failed, Federal forces maintained control of Jacksonville for the rest of the Civil War, a key holding that both disrupted Confederate trade and allowed Florida blacks to more easily join Union ranks.