While many Americans are familiar with the song, “The Yellow Rose of Texas,” few know the story of Emily West, the African American woman who was the inspiration for its creation. In the excerpt below from a longer article that first appeared in 1996, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill English Professor Trudier Harris explains that history.

I would venture to say that most Americans are familiar with the folksong, “The Yellow Rose of Texas:” If they cannot recall all of the lyrics, there is still a resonant quality about the song. I would also venture to say that few of those Americans—Texans notwithstanding—have reflected overly long on the implications of the fact that the song is not just about a woman, but about a black woman, or that a black man probably composed it. Scholars such as Martha Anne Turner have linked the song to its contextual origins—that of the Texas war for independence from Mexico in the 1830s and a specific incident in 1836—and others have argued its irrelevance to that event. It was only in 1989, however, when Anita Richmond Bunkley published Emily, The Yellow Rose, a novel based on the presumed incidents that spawned the fame of the yellow rose, that the fictionalized expansion of the facts encouraged a larger and perhaps different audience to become aware of the historical significance of Emily D. West, the hypothetical “Yellow Rose of Texas:”‘ This publishing event certainly re-centered the song and the incident in African-American culture, for over many years and numerous versions, the song had been deracialized. Bunkley, herself an African American woman, researched the complex history of another African American woman and imaginatively recreated and reclaimed it.

The presumed historical facts are simple and limited. Emily D. West, a teenage orphaned free Negro woman in the northeastern United States, journeyed by boat to the wilderness of Texas in 1835. Colonel James Morgan, on whose plantation she worked as an indentured servant, established the little settlement of New Washington (later Morgan’s Point). When Santa Anna and his troops arrived in the area, he claimed West to take the place of his stay at home wife in Mexico City and the traveling wife he had acquired on his way to Texas. The traveling wife had to be sent back when swollen river waters prevented him from taking her across in the fancy carriage in which she was riding. Santa Anna was either partying with West or having sex with her when Sam Houston’s troops arrived for The Battle of San Jacinto, thus forcing him to escape in only a linen shirt and “silk drawers;” in which he was captured the next day. West’s possible forced separation from her black lover and her placement in Santa Anna’s camp, according to legend, inspired her lover to compose the song we know as “The Yellow Rose of Texas.”

Publicity surrounding the hotel in San Antonio that was named after Emily Morgan asserts that West was a spy for Texas. Other historians claim that there is absolutely no tie between West and the events of the Texas war for independence from Mexico. Still others claim that it was only West’s heroic feat of keeping Santa Anna preoccupied that enabled the Texas victory. Broadening perceptions of how texts are created and the purposes to which they are put provide the context, during the course of this paper, from which I want to explore West’s story and take issue with the assigning of heroic motives to her adventure.

Bunkley’s novelistic representation of the events provide motive, emotion, sentiment, and introspection to flesh out the bare bones of the presented history. According to Bunkley, a twenty year old orphaned Emily D. West journeyed to Texas in the hope that its status as Mexican territory would help her to realize more freedom than she had experienced in the so called free environment of New York. Upon arriving in Texas, West discovered that her freedoms were minimal, that the land was much more harsh than she had anticipated, and that her circumstances were not appreciably different from those of enslaved African-Americans. She fell in love with a black man, a musician, thought to be a runaway from slavery. Bounty hunters and the pressures of the fast-approaching war for independence from Mexico interrupted their sustaining relationship. Her lover attempted to get away from his pursuers and the war, while West found herself in the midst of both; their separation led to his composing “The Yellow Rose of Texas.”

Unfortunately for West, the plantation on which she worked lay directly in the path of the oncoming Mexican soldiers, led by Santa Anna. Upon arriving, burning most of the plantation, and killing several of its inhabitants, Santa Anna discovered West and ordered that she be taken captive. Forced to engage in sex with…Santa Anna, West unknowingly but greatly aided the Texan cause. After an…encounter with West, Santa Anna fell into a slumber from which he could not arouse himself sufficiently before Sam Houston’s troops attacked his camp, killed many of his soldiers (who were quickly scattered without the commanding voice of their leader), and captured Santa Anna. During the battle of San Jacinto, West made a convenient escape.

The presented history and the novelistic depiction of it are certainly the stuff of which legends are made, and Bunkley appropriate subtitles her novel “A Texas Legend.” As the events come to us today, therefore, West is considered to be “the yellow rose;” the woman in the song, and the incident of its composition is equated to lovers being separated during the war for Texan independence, with West subsequently playing her alleged historical, legendary role with Santa Anna. The black woman, Santa Anna, the black male composer, April 21,1836, The Battle of San Jacinto, the song—these are the people, the time, the place, the incident, and the creation surrounding it that have merged history, legend, biography, and musical composition. No matter who would desire otherwise, the links are now inseparable in viewing the story of the song and its presumed subject, Emily D. West.

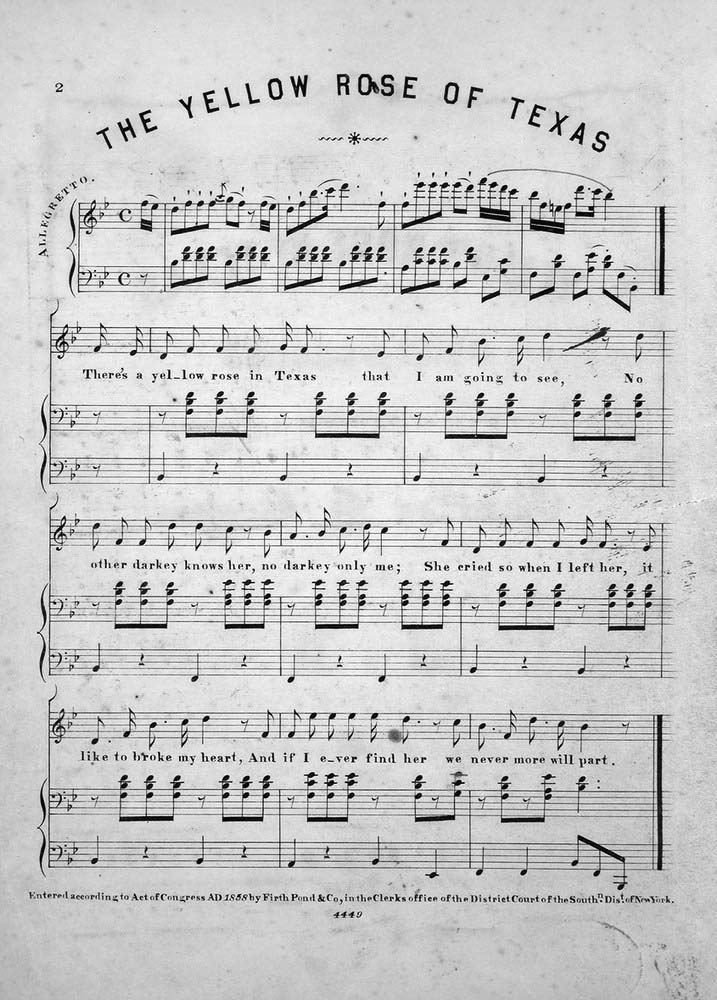

What fascinates about the story beyond its legendary proportions is its centering of an African-American woman in a significant piece of American history. The forced separation of the lover from his loved one, with the events of the war as backdrop, led to the composition of the song. Following are the first verse and the chorus:

There’s a yellow rose in Texas

That I am a going to see

No other darky [sic knows her]

No one only me

She cryed [sic] so when I left her

It like to broke my heart

And if I ever find her

We nevermore will part.

Chorus

She’s the sweetest rose of color

This darky every knew

Her eyes are bright as diamonds

They sparkle like the dew

You may talk about dearest May

And sing of Rosa Lee

But the yellow rose of Texas

Beats the belles of Tennessee.

The centering of the black woman in the song and its ensuing historical significance comprise an unprecedented circumstance matched only by the second fascination—a love story between black people that was powerful enough to be immortalized in song. The woman and the song serve Texas history well, but they serve African American history, folklore, and culture even better…

A search through African American folklore reveals that few black women have been painted as desirable and sexually healthy persons. One little known strand of the lore has vestiges of viewing black women in the way that Emily D. West came to be viewed in “The Yellow Rose of Texas:” I refer to nineteenth-century courtship rituals during slavery and Reconstruction. These rituals suggest the black women to whom they were addressed were viewed as special females indeed…. I like to read “The Yellow Rose of Texas” as presaging that strand of African-American folklore. I like to think that the composer of the song so revered the woman he compared to a rose that his choice of expressing her beauty through nature elevated her to a position of value that has few comparative patterns. We cannot say, “the song about Emily’s value is like…” because there is no immediately comparable “like:” What we can say is that the separation, the pain this composer felt, led him to create a song about a beautiful woman, one who became the center of his existence as well as his creativity. The fact that she was “yellow” (mulatto) was less important to him than the human longings that are the essence of love.

How he viewed her as woman, lover, universal human partner, however, is obviously not how she or the legacy she left came to be used in American history or folklore studies. Her name has certainly served the tourist trade in San Antonio. Her presence or not at The Battle of San Jacinto has engaged many lively minds….In being transformed into a state icon, West loses the individuality of a personal life, but not the individuality of a symbol. Her name, the song, and the circumstances of Texan triumph become emblems of the best the American frontier had to offer…. In this script, West is subsumed under the great American concept of Manifest Destiny—with a slight detour southward—that did not allow for fissures in the sometimes fragile pot of nationalism. The history and the song suggest that in the killing frontier, where true blooded Americans were always subject to attack by some ungodly force, these Americans lived up to the best of their inheritance from back east; they fought, some of them died, but they ultimately triumphed over the forces of evil and repression….

West’s physical body, subject to exploitation as readily as those black persons who were legally enslaved, serves in this legendary capacity to elide the brutality to which black female bodies were potentially victim. There is a clash between the ideal (romanticized Texas history) and the real (a black woman being raped during the process of history-making events). By elevating West’s role in the capture of Santa Anna, by making her a seeming voluntary participant in the sequence of events, commentators and appreciators of the tale and the song could effectively deny slavery or certainly deny black women’s exploitation during slavery (since technically West was not an enslaved person). More specifically, they deny the brutal fact of rape, which West experienced not only from Santa Anna, but from a Texas soldier as well. Territorial and national unity implied in the events behind the song does not allow for the fact that black people were treated as badly, in this instance, by the Texans as they were by the Mexicans. The song becomes a pretty site, a pretty body, on which troubling issues about war, slavery, and sexual exploitation can be overlooked in the praise for a beautiful woman who evoked images of a yellow rose…

Ultimately, “The Yellow Rose of Texas” is a fascinating study in elision, erasure, and transformation. The song, its subject, its history, and its creator have all been used. Obviously there are good uses and bad uses to which any work of art, any historical event, can be put. Add to these usual patterns the fact of folklore and legend and the uses become even more expansive. Where all of this ends, however, is with the exploitation of the creator of the song. He who created the yellow rose is more lost to us than the subject about which he sang. Yet it is because of this black man’s song that researchers have been able to uncover as much as they have about Emily D. West. We have all, collectively, “taken his song and gone” far beyond the pleasure of appreciating it, far beyond the popular interest in transmitting it. Folklorists, historians, and scholars have made the song as much a legend as its subject, have made the events surrounding the composition of it as much an issue of erasure of composer as erasure of Emily D. West.