In the article below independent historian Clarence Spigner analyzes Sergeant Rutledge and the other major films of the college football star, early National Football League player, and actor Woody Strode.

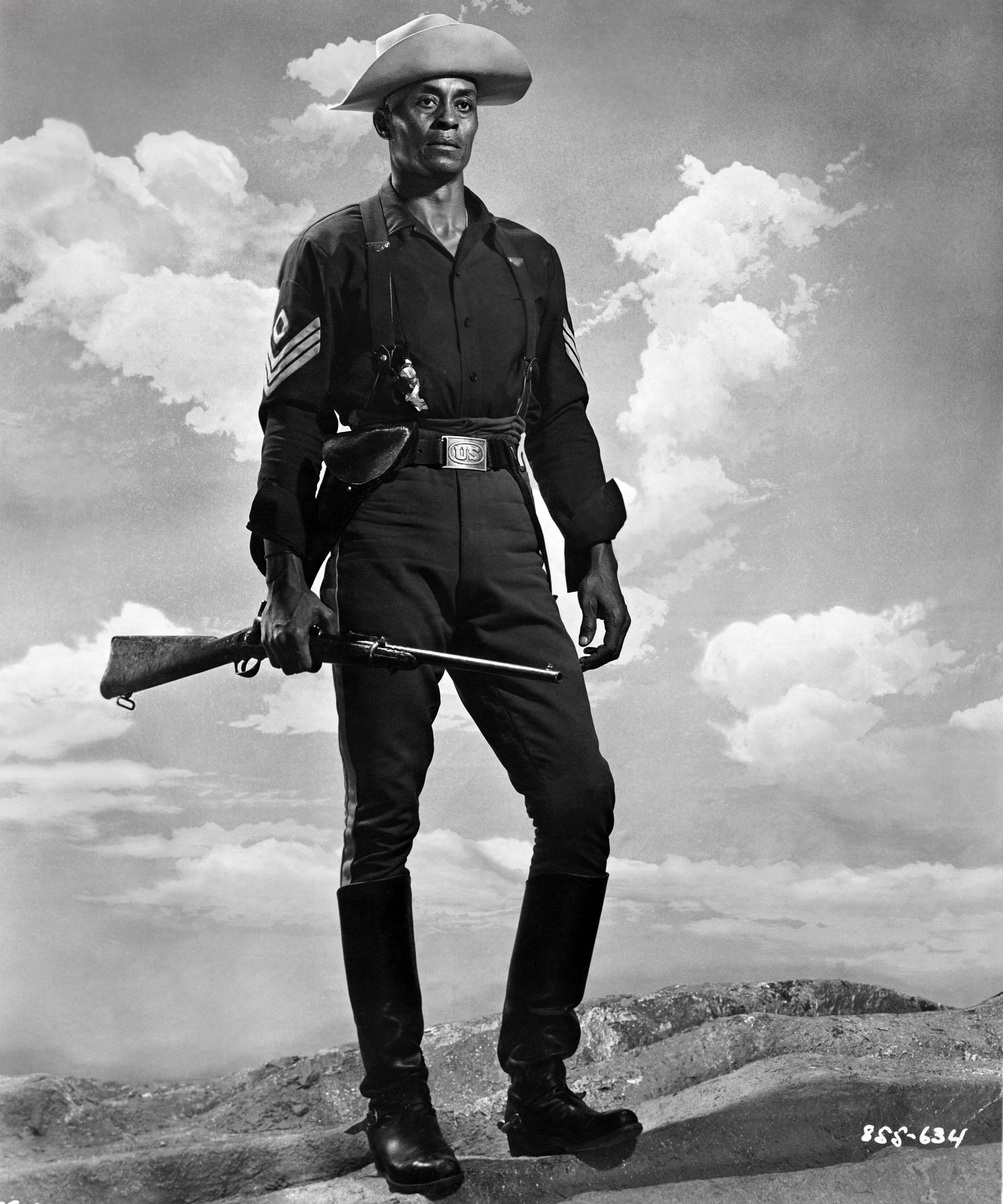

Sergeant Rutledge is a 1960 western film from Warner Brothers and the director John Ford. It featured African American athlete turned actor Woodrow Wilson “Woody” Strode in his major film role and the first of four films he did with Ford. Sergeant Rutledge was significant both because Strode was one of the earliest Black actors to play a leading role alongside white actors, and because it was one of the first movies to depict the then little-known Buffalo Soldiers who comprised approximately 10% of the U.S. Army in the West between 1866 and 1900.

The film’s plot is simple. The time is circa 1880s. Major Custus Dabney, the post commander, is killed along with his teenage daughter Lucy, who is raped and strangled to death. Sgt. Braxton Rutledge, portrayed by Strode, is a former slave who is now a Buffalo Soldier. He is accused of both murders and court-martialed. In a series of flashbacks from the trial, the audience is introduced to Rutledge and the other main characters in the film. Although circumstantial evidence points to Rutledge’s guilt, eventually the truth comes out that the post’s merchant, Chandler Hubble (played by Fred Libby), is responsible for both murders.

Buffalo Soldiers were African American ex-slaves who escaped the racially oppressive South and made their way West to become soldiers on horseback in the 9th and 10th cavalry under the command of white officers. As was customary during the first half of the 20th century, the U.S. Cavalry was always portrayed as white men courageously fighting Native Americans almost always to protect white settlers or to punish Indians for attacking and killing those settlers. Hollywood’s depictions of this history was through a white lens and reinforced the white civilization-Indian savagery dichotomy that held sway in movies and more generally in popular culture through the first eight decades of the 20th century.

Only in the 1980s did historians begin to interrogate and challenge this narrative. Of course, Black soldiers did not exist in the popular imagination of the West before then. Thus, any depiction of them on film in 1960 as cavalrymen was unusual. Unfortunately, the depiction of marauding Indian savages carried over into Sergeant Rutledge as well. As the African American comedian, writer, and actor Richard Pryor prophetically cautioned in the 1980s, Blacks bragging about having helped whites kill off the Native Americans was yet another reason for people to hate us. The real story of Black soldiers and Native Americans is far more complicated and nuanced, but none of that emerged in Sergeant Rutledge.

Sergeant Rutledge was released nearly four decades before Buffalo Soldier (1997) appeared as a television film starring Danny Glover. In this film, Native Americans are presented more sympathetically but the emphasis, as in Sergeant Rutledge, remains on heroic Black cavalrymen fighting Indians who in this case are Apaches. While a number of historical works had emerged to portray the Buffalo Soldiers more accurately, Hollywood continued its mostly stereotyped depictions, only occasionally giving a nod to their actual lives and experiences. Consequently, television was as patronizing toward Buffalo Soldiers on the small screen as movies were on the big screen. Buffalo Soldiers on TV emerged periodically in such popular westerns as Rawhide in 1961 and High Chaparral in 1968, but those early depictions also rested on stereotypes.

John Ford, the white film director usually credited with his brave stance in bringing Sergeant Rutledge to the big screen before the height of the civil rights movement, actually had considerable cinematic experience promoting racism and miscegenation, as evident in one of his most popular westerns, The Searchers (1956), starring John Wayne. The rape of a white woman by a Native American was unspoken but strongly implied. Ford’s film centered on the racist, Ethan Edwards, who fought for the Confederacy and now sought revenge on Comanches.

One can only speculate as to whether Ford intended to be progressive or reactionary in his depictions of other characters in the Sergeant Rutledge film. He cast then leading white actor Jeffrey Hunter as Capt. Tom Cantrell, a white savior who at first believed Rutledge was guilty but who eventually successfully defended him during the sergeant’s court-martial, which was the backdrop of the film.

Constance Towers, the white female lead, portrayed Mary Beecher, whose character sought to defend Rutledge even when all others except the loyal Black soldiers under his command declared him guilty. Ford inserts a curious scene in Sergeant Rutledge where the Sergeant and Beecher are alone in a cabin at night and Rutledge takes off his shirt to allow her to tend to the wounds he received defending her from Apaches. One wonders what message Ford was trying to convey since there was no logical reason for Rutledge to disrobe and display his physique in the presence of the white woman. Perhaps director Ford was toying with the audience regarding the taboo of interracial sex. As other film critics have noted, the production of Sergeant Rutledge in 1960 was probably as opportunistic as it was timely.

Hollywood executives did not want Woody Strode for the role of Braxton Rutledge. They had in mind the handsome, Bahamian-born African American actor Sidney Poitier, who by 1960 had already built his own screen image as a non-threatening Black man in such dramatic films as No Way Out (1950) where he played a physician who endured name-calling and spit in the face, or Edge of the City (1957), where he was killed by a bigot who called him an ape. In another 1957 film, Band of Angels, he was through most of the film Rau-Ru, the educated but loyal slave of Clark Gable’s character, Hamish Bond. And in 1959 he was the acquiescent Rev. Msimangu in the apartheid-themed Cry the Beloved Country. Ford, however, knew what the executives did not: that audiences would not believe an actor of Poitier’s screen persona could rape and murder a white woman. Ford’s instincts were correct. He insisted the larger, more physical Strode would be a better fit in the role. To director Ford, the physical attributes and the persona of Strode fit his and the general white society’s constructed stereotype of Black/African American men.

Woodrow Wilson Strode was 6-foot-4 and of African American and Native American heritage. As an ex-UCLA athlete who played in the National Football League for the Los Angeles Rams from 1946 to 1948 before turning actor in the early 1950s, he seemed to follow the career path of college athlete, singer, actor, and activist Paul Robeson. Strode, however, was not political. He was far more symbolic of stoic Black male masculinity and rarely spoke out on social or political issues. Former professional athletes such as Fred Williamson and Carl Weathers took similar routes in the 1970s era of the Blaxploitation movies.

As Braxton Rutledge, First Sergeant of the 9th U.S. Cavalry, Woody Strode was strong and confident, with high cheekbones, piercing eyes, and a hard stare. He was similar to his contemporary, the African American actor Brock Peters, who would later appear in To Kill a Mockingbird (1962), which was also based on a Black man charged with raping a white woman. Although the film and Strode’s portrayal of Rutledge received praise by Black film critics and moviegoers, one has to remember that both were starved for depictions of Blacks on the silver screen that were not of the Stepin Fetchit or Rochester Anderson variety.

Not that the Hollywood executives really cared what African Americans felt about Sergeant Rutledge or Buffalo Soldiers. They would recognize an African American market for films depicting Black characters only in the 1970s. #Oscarsowhite, the Twitter-based movement that critiqued the absence of Black roles in Hollywood, was six decades into the future. Racism, however, was rampant in 1960 throughout Hollywood and the popular market its films addressed. Only a handful of black actors made it to movie screens in non-subservient roles. Black actress Dorothy Dandridge in Carman Jones (1954) and Island in the Sun (1957) was perhaps the lone Black actress that would have been known to some among white audiences, as was Calypso singer, actor, and later activist Harry Belafonte. Belafonte took chances in films like Carman Jones (1954) with Dandridge and in Odds Against Tomorrow (1959). But he also echoed Poitier’s caution as in the apocalyptic thriller, The World, the Flesh, and the Devil (1959). Ultimately Blacks in that era had no power in Hollywood and Sidney Poitier stood virtually alone in his ability to avoid depicting characters he felt would embarrass Black people.

Strode, perhaps in spite of himself, inadvertently established a noble Black presence on the screen with his portrayal in Sergeant Rutledge. He became a magnificent symbol for the then emerging civil rights movement and the later ideology of Black Power. There is no evidence that Strode set out to represent the ideals of Paul Robeson or professional boxer Muhammad Ali, or to be positive Black role model. This was not the style of Strode. Yet his image and persona produced positive statements about the Black/African experience. These came less from Sergeant Rutledge than his on-screen explosion of Black defiance as the gladiator slave Draba in Spartacus (1960), set in the Roman Republic during the time of 111-71 BCE. The riveting scene of Draba leaping from the arena and hell-bent on killing the Roman emperor ignited Black audiences. Strode was nominated for the Golden Globe Award for that portrayal. Strode, whether intentional or not, symbolized the soul of the 1950-1960s civil rights movement. His physicality and demeanor came to represent Black Power. This can be witnessed later in the 1960s as he played Stony, the gunslinger assassin, featured in the iconic opening scene at the train station in Once Upon a Time in the West (1968).

Sergeant Rutledge was not a box-office success, but it was also not a bomb. Looking back more than six decades later, the film does provide a retrospective analysis of American race relations and Black history through the lens of the white controlled media. We should not be surprised that given that lens, the film has flaws. It can only be through sources such as BlackPast that we can come away with a truer, valid, and more objective understanding of Buffalo Soldiers, Black Hollywood, and the entire Black/African American experience.