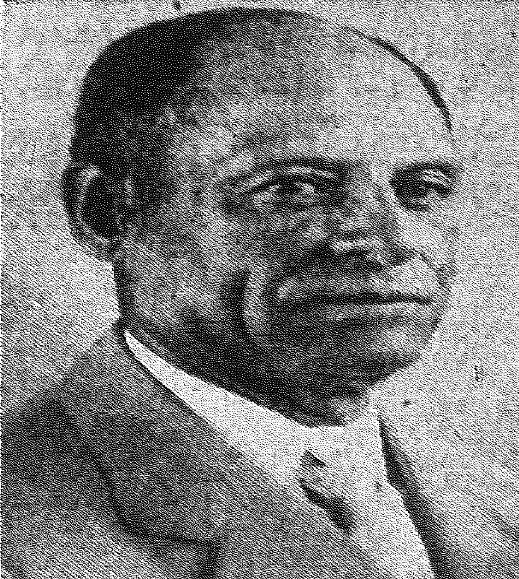

It took nearly a century for Philip Jordan to receive proper recognition as a first-hand observer and informal reporter on the Russian Revolution of 1917. Believed to be the son of a slave, Jordan was born in Jefferson City, Missouri, in 1868. He spent his youth as a reckless street fighter and alcoholic, until at age 21 when he was hired as a valet for David Rowland Francis, who at the time was governor of Missouri. Over the years Jordan became a trusted, dependable, loyal member of the Francis family. He was especially close to the governor’s wife Jane, who repaid his good work by teaching him to read and write and excused his occasional overindulgence in hard liquor.

When Francis was selected by President Woodrow Wilson in 1916 to serve as U.S. Ambassador to the Russian Empire, Jordan traveled with the Ambassador to St. Petersburg, the capital of the Empire. Arriving at the American Embassy on April 13, 1916, Jordan dismissed the Russian cook and took responsibility for supplying food, drink, and even black market goods to the embassy. But events soon overtook diplomacy as the Russian Revolution in 1917 rapidly changed the political landscape. Defeated, undisciplined soldiers fled the front line for the capital as did uprooted peasants as the Russian aristocracy lost control of the country to rival moderate and radical socialists, labor unionists, and anarchists.

From the embassy’s windows Jordan could easily observe frequent, boisterous protest marches and other demonstrations that sometimes turned violent. A frequent embassy guest taught him enough of the Russian language to make himself understood by the locals and despite the chaos he did not fear roaming city streets where he saw police and dissidents shooting to kill each other.

Jordan regularly corresponded with Jane Francis, who had declined to accompany her husband to St. Petersburg. In one letter to her he commented: “We are all setting on a bomb Just waiting for someone to touch a match to it . . . These crazy people are Killing each other Just like we swat flies at home.” Jordan, the Ambassador’s valet was describing the unfolding revolution. Trapped in one street battle, he told of lying flat on his stomach to avoid being hit by rapidly fired bullets. On other occasions he wrote about food shortages, horrendous crimes committed by prowling thugs, attending an Orthodox Church funeral service, the ambush and slaughter of horse-mounted Cossacks who had previously terrorized the peasantry in the name of the Emperor, and the daily struggle to keep the U.S. Embassy functioning.

Ambassador Francis left Russia in 1918 and Jordan accompanied his employer on visits to Buckingham Palace in Great Britain and the White House before arriving home in Missouri. Thanks to a researcher who in the late 1970s found Jordan’s letters housed in the Missouri Historical Society, and to Helen Rappaport’s recent bestselling book on the Russian Revolution, we can appreciate Jordan’s unique perspective on that momentous event as a working-class foreigner. After Francis died in 1927, Jordan relocated with the ambassador’s son to Santa Barbara, California, where he died in 1941 from cancer.