Screenwriter, filmmaker, actor, and social critic Carlton Moss was born in Newark, New Jersey, on February 14, 1909. The son of Frederick Douglass Moss, a coachman for an affluent family, and Sarah Vincent Moss, he grew up both in New Jersey and North Carolina. As a child, he was enamored with Black history. He later stood out as a student at Morgan College (now Morgan State University) in Baltimore, Maryland. There he acted in and wrote for the Morgan Players theater troupe.

After graduation in 1930, Moss moved to New York City’s Harlem, hoping to launch a career in theater. He started as a theater doorman but also spent much time absorbing and analyzing Black popular culture in the nation’s most influential Black community. Moss was especially concerned about stereotypic images of Blacks portrayed on the radio. In 1931 when the National Broadcasting Company (NBC) hired him as its first African American writer, he used the opportunity to realistically and humanely portray Blacks in his series of Careless Love radio plays set in the South. The 15 to 30-minute plays boasted professional Black actors. They stood in sharp contrast to the buffoonery of Amos ‘n’ Andy characters acted by whites who were wildly popular during the Great Depression and beyond.

In the mid-1930, Moss acted in films by Oscar Micheaux but separated from him over the Black filmmaker’s policy of only hiring white camera operators. He next found work in the Federal Theatre Project (FTP) at Harlem’s Lafayette Theater as John Houseman’s chief assistant director. There he handled artistic matters, publicity, and marketing for its productions. When Houseman and Orson Welles exited the Negro Theatre Project (the Black unit of the FTP) in 1936, Moss and two other Blacks, Harry Edwards and Augustus Smith, took control. They redirected productions to emphasize social inequity and resisting injustice. Underfunding and the unsubstantiated charge of Communist influence by conservative politicians shut down the FTP in 1939.

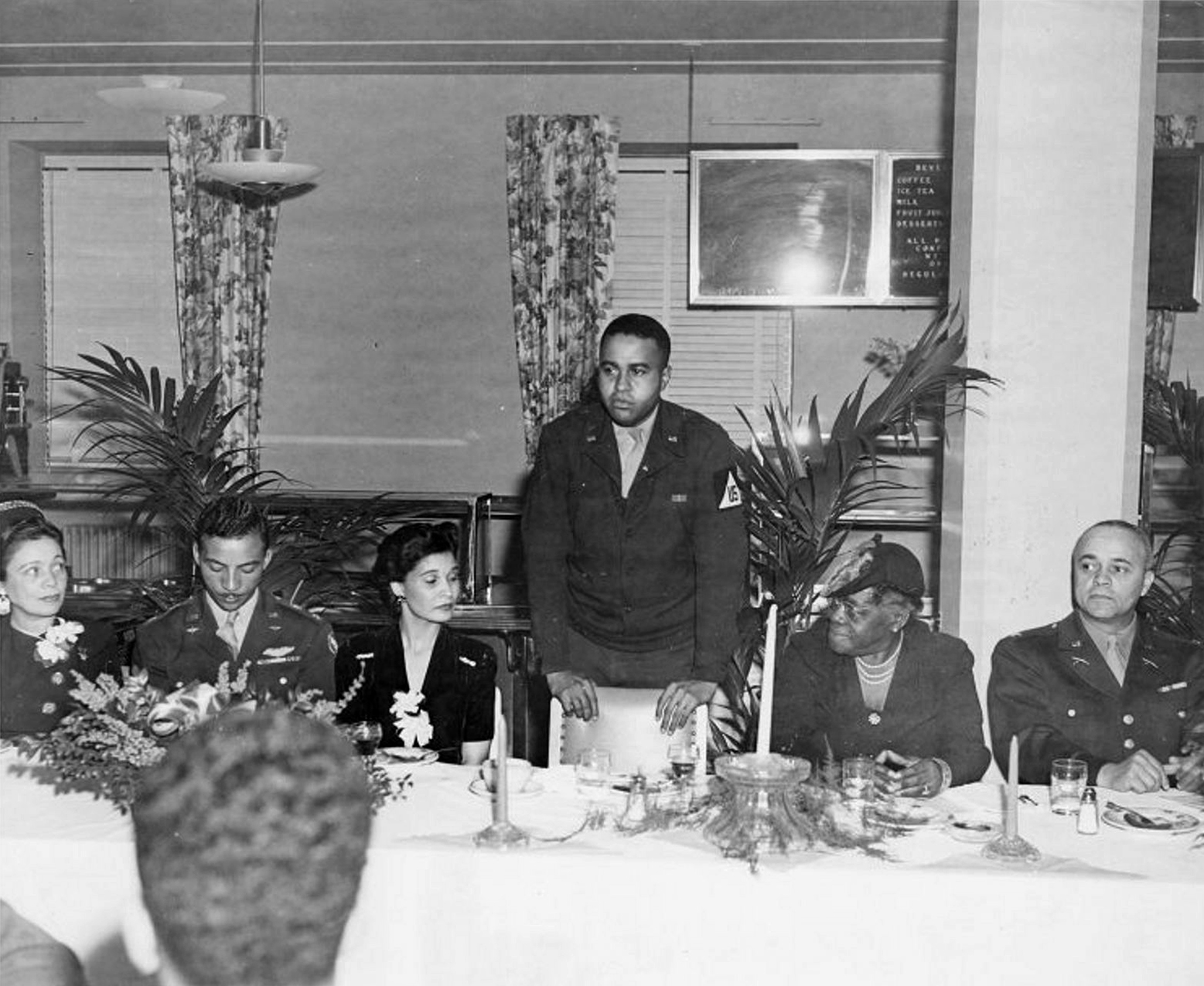

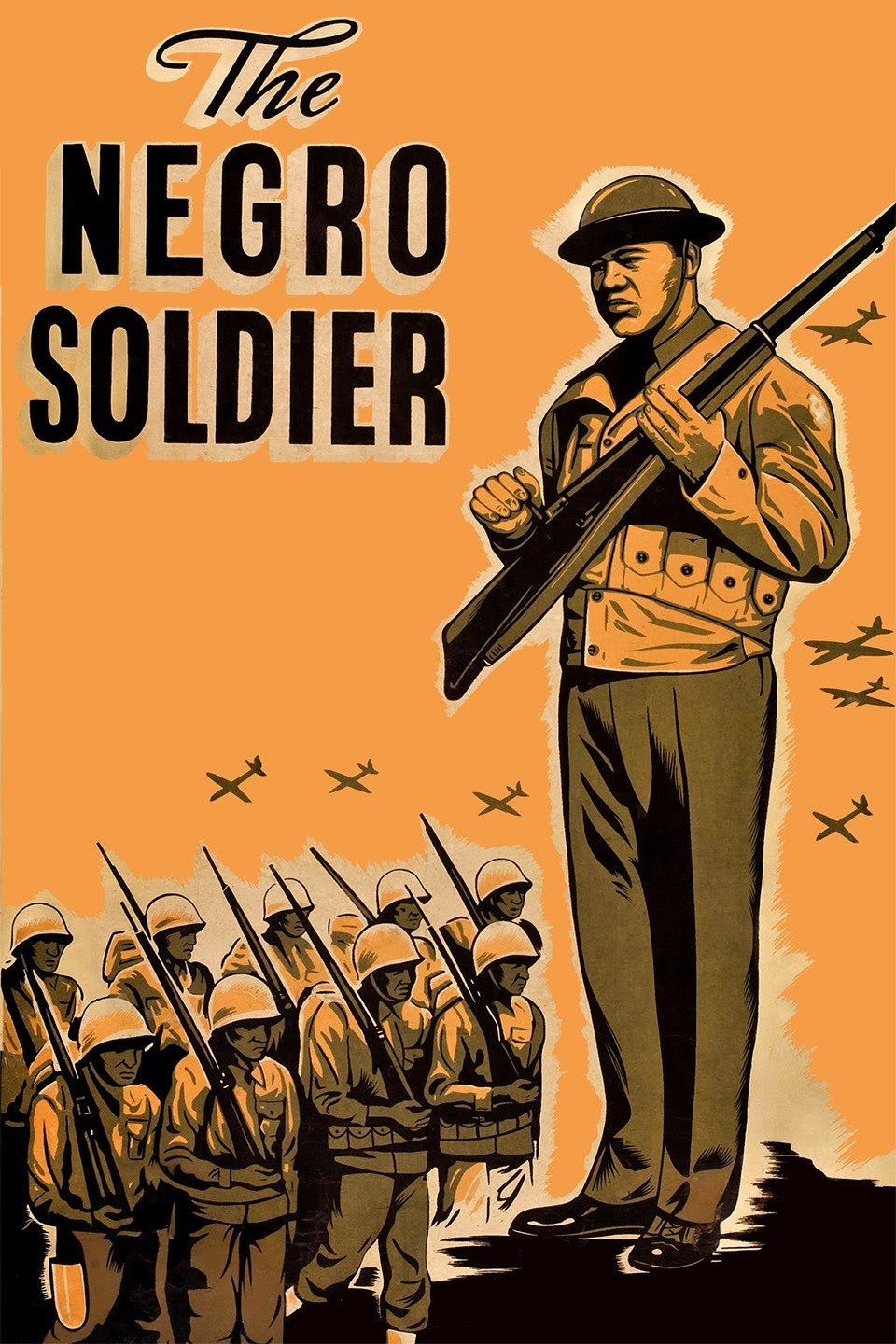

Within months after the United States entered World War II in December 1941, pressure from Black leaders to ease racial discrimination against Black in the military led to the federal government launching a media campaign to inspire loyalty in Black communities. The most effective effort was a “documentary film” initially assigned to whites to direct, which eventually fell to Moss. Titled The Negro Soldier, much of the film’s anger and militancy were toned down on the advice of movie director Frank Capra. Nonetheless, the final product released in 1944 highlighted African American soldiers’ long, valiant service. Though Moss regretted he could not express his true sentiments regarding America’s anti-Black racism, the film is remembered as his most significant career achievement.

Persistent racism in the entertainment industry meant that Moss would never have the opportunity to fulfill his desire for steady employment or unfettered artistic expression in Hollywood. Moss survived by teaching and making educational and industrial films for schools, corporations, and the government. He believed that a copy of The Negro Soldier sent to President Harry S. Truman helped to persuade him to issue an Executive Order in 1948 outlawing racial discrimination in the military. Moss outlived his wife, Lynn Moss, but died in Los Angeles on August 10, 1997, at the age of 88.