New York Times literary critic, author, and teacher Anatole Broyard was born in New Orleans, Louisiana, on July 16, 1920, the son of carpenter Paul A. Broyard and Edna Miller, two light-skinned African Americans. With the nation in the throes of the Great Depression his family moved from the city’s historic French Quarter to a neighborhood in Brooklyn, New York. It was then that his father decided to pass for white in order to secure a job.

World War II interrupted Broyard’s studies at Brooklyn College. He adopted a white identity when he entered the U.S. Army, rising to captain and, ironically, was put in charge of an all-black cargo loading battalion. Soon after the war ended he divorced his first wife, Aida Sanchez, a mixed-race Puerto Rican; took advantage of the G.I Bill to study at the New School for Social Research; and with money he had saved during the war, opened a bookstore in Greenwich Village that facilitated his contact with writers such as Delmore Schwartz, Maxwell Boderheim, Max van den Haag, and Chandler Brossard. In the late 1940s Broyard began submitting writings to top-tier intellectual magazines including Partisan Review and Commentary. His 1954 article in Discovery titled “What the Cystoscope Said,” concerning his father’s losing battle with cancer, announced to the literary world that a formidable new talent had arrived.

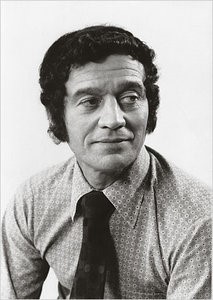

As his notoriety grew, speculation about Broyard’s racial identity was whispered about by both whites and blacks. His closest white associates had heard rumors of his black ancestry but were loath to mention it to him—the very suggestion he quickly deflected or caused him to fly into a rage. When his photo appeared in Time magazine in 1958, black poet-novelist Arna Bontemps told his friend Langston Hughes: “His picture . . . makes him look Negroid. If so, he is the only spade among the Beat Generation.”

By the early 1960s Broyard was working odd jobs related to advertising and teaching classes part-time at the New School. In 1962, he married Norwegian American dancer Alexandra Nelson. For six years he worked for the advertising agency Wunderman Ricotta & Kline, commuting from the family home in Connecticut to downtown Manhattan. Later in the decade he penned several front-page reviews for the New York Times Book Review, and thereafter replaced Christopher Lehmann-Haupt as the publication’s daily reviewer. His perch as editor at the Times made him one of the nation’s leading arbiters of taste and a cultural gatekeeper, a man’s whose opinions could bolster or devastate one’s literary aspirations.

Collections of Broyard’s reviews, Aroused by Books (1974) and Men, Women, and Other Anticlimaxes (1980), were published by Random House and Methuen, respectively. In 1984 he began writing a column in the Book Review.

Broyard retired from work at the Times in 1989 and died October 11, 1990 of prostate cancer. His two autobiographical works published posthumously are Intoxicated by My Illness and Other Writings on Life and Death (1992) and Kafka Was the Rage: A Greenwich Village Memoir (1993). In 1996, Harvard University professor Henry Louis Gates, Jr. wrote a penetrating meditation on Broyard’s life in The New Yorker with particular attention to his complicated attempt to pass as white. When Broyard’s darker-skinned sister, Shirley, attended his memorial service, white mourners where shocked to see she was black. Fearing his anger, not even Broyard’s wife shared the secret of his racial heritage to their children, Todd and Bliss, until after his death.