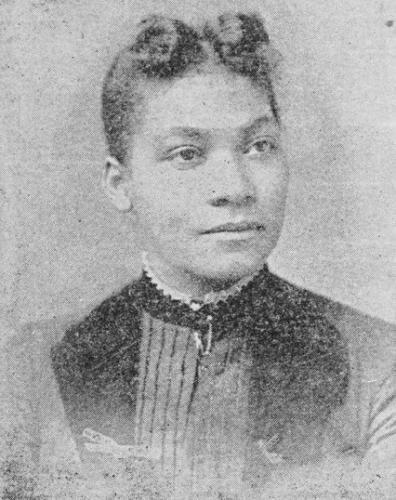

Georgia E. Lee Patton, physician and missionary, was born a slave in Grundy County, Tennessee. Her father died before her birth, leaving her mother to care for Patton and her siblings. After moving to Coffee County, Tennessee in 1866, her mother supported the family by working as a laundress until her death in 1880.

Educational opportunities for former slaves in Coffee County were limited but Patton managed to complete high school, the only one in her family to do so. By February 1882, Patton’s siblings had saved enough money to send her to Central Tennessee College in Nashville. Patton faced financial challenges while in school and frequently missed class to work. She graduated in 1890. In 1893, Georgia Patton earned her medical degree from the Meharry Medical Department of Central Tennessee College as one of the school’s two female graduates. Only one other woman previously had graduated from Meharry.

After graduation, Patton went to Liberia as a missionary where she hoped to use her new medical skills to assist Liberians in need. When her church’s missionary society refused to fund her trip, Patton raised the money on her own. In April 1893, she left for Liverpool, England. On the ship, she roomed with Ida B. Wells-Barnett, the famous anti-lynching activist who recorded the women’s seasickness during the voyage. Patton then travelled to Monrovia, Liberia, where she worked as a doctor and missionary for two years.

After her two years in Liberia, Patton returned to school in the United States. However, during her return trip, she contracted tuberculosis and would never regain full health. Settling in Memphis, Tennessee, Patton opened a private medical practice and became the city’s first black female doctor. She also became the first black woman to receive both physician’s and surgeon’s licenses from the state of Tennessee. In 1897, she married David W. Washington, Memphis’s first black postal carrier. Patton and Washington both actively volunteered in their churches and in the community. Every month, Patton donated ten dollars to the Freedmen’s Aid Society. Her generosity earned her the nickname “Gold Lady.” In 1899, she had the couple’s first son, Willie Patton Washington, who died soon after his birth.

In the last few years of her life, Patton worked sporadically because of her health problems. She died in Memphis four months after giving birth to her second son, David W. Washington, Jr., who died soon after his mother. Georgia E. Lee Patton was buried in Memphis’s Zion Cemetery.