Tensions leading up to the Civil War often manifested themselves through conflicts over the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850. The Oberlin-Wellington Rescue was one such instance of this. It was a struggle between supporters of slavery and supporters of freedom, the outcome of which would decide the fate of a young African American man named John Price.

In 1856, eighteen-year-old Price escaped from his owner John G. Bacon and made his way from the Mason County, Kentucky plantation to Oberlin, Ohio. In addition to being the home of liberal-minded Oberlin College, Price’s destination was well known as a station along the Underground Railroad and as a center of abolitionist support.

Price lived in Oberlin for two years, mainly with black laborer James Armstrong. On the morning of September 13, 1858, the son of a wealthy white landowner came to Price with an offer of work as a field laborer. In actuality, the offer was a conspiracy orchestrated on behalf of Anderson Jennings, ringleader of a slave-catching posse and the neighbor of Price’s former owner. Anderson and his companions seized Price and took him nine miles south to the Wadsworth House hotel in Wellington, Ohio to begin the journey back to Kentucky.

By noon that day, news had reached Oberlin and inspired abolitionists to march south after Price. Six hundred citizens from Oberlin and Wellington surrounded the Wadsworth House. Abolitionists Charles Langston, John Watson and O.B. Wall attempted to resolve the situation legally both by lobbying the constable to arrest the slave-catchers and then by filing a writ of habeas corpus for Price, but to no avail. After failed negotiations with captor Jacob Lowe, Langston gave up, saying, “We will have him anyhow.”

The crowd sprang into action: three men rushed the door guards to begin a diversionary struggle in the hotel. Theology student Richard Winsor led Price out through a window to a buggy and rushed him back to Oberlin. Future Oberlin College President James Fairchild harbored Price in his home until Price’s escape to Canada was secured.

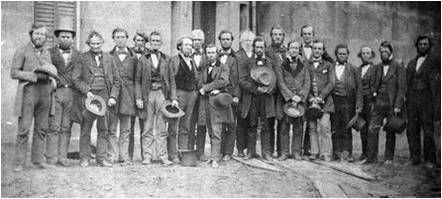

Thirty-seven of the individuals involved in the rescue were arrested for violating the Fugitive Slave Law. Simon Bushnell and Charles Langston were the first to be put on trial, with abolitionists Rufus Spalding and Albert Riddle serving as their attorneys. Bushnell and Langston were convicted and sentenced to prison.

In an act of solidarity, the remaining defendants chose to remain in jail as they awaited trail. Popular opinion was on their side, with dozens of rousing pro-abolition speeches in and around the courthouse, antislavery tracts and a newspaper called The Rescuer published from inside the prison. Eventually the slave-catchers were arrested and charged with kidnapping. In a plea bargain to drop kidnapping charges against them, the slave-catchers allowed for the release of the abolitionists still in prison. By July 7, most of the rescuers had returned to Oberlin “amid great celebration.” Bushnell, the last of the imprisoned rescuers, returned to a jubilant crowd on July 11, 1859.