On July 14, 1946, four African American sharecroppers were lynched at Moore’s Ford in northeast Georgia in an event now described as the “last mass lynching in America.” Yet the killers of George Dorsey, Mae Murray Dorsey, Roger Malcolm, and Dorothy Malcolm were never brought to justice. The violence and public outcry surrounding the event reflected growing African American challenges to Jim Crow in the post-World War II years as well the failures of state and federal authorities to address racial inequality and violence in the South.

A fight between Roger Malcolm and his wife Dorothy sparked the crisis that unfolded in mid-July in Walton County, just sixty miles outside of Atlanta. On July 14, Malcolm was arrested by local authorities after stabbing white overseer Barnette Hester who had intervened in the domestic conflict. Hester may have had a sexual relationship with Dorothy Malcolm. Eleven days after this assault on July 25, white landowner J. Loy Harrison drove Dorothy Malcolm and fellow sharecroppers George and Mae Murray Dorsey to the Monroe, Georgia, jail to bail out Roger Malcolm. A large white mob stopped Harrison and the two couples on their return trip near the Moore’s Ford Bridge on the Apalachee River. What happened next was hotly debated by Harrison and other witnesses. Loy Harrison was reputed to be a member of the Ku Klux Klan, as were many others who gathered at Moore’s Ford Bridge. Ultimately, the mob beat the sharecroppers before tying them to a tree and shooting them to death. George Dorsey was a World War II veteran recently returned from service in the Pacific while Dorothy Malcolm was seven months pregnant.

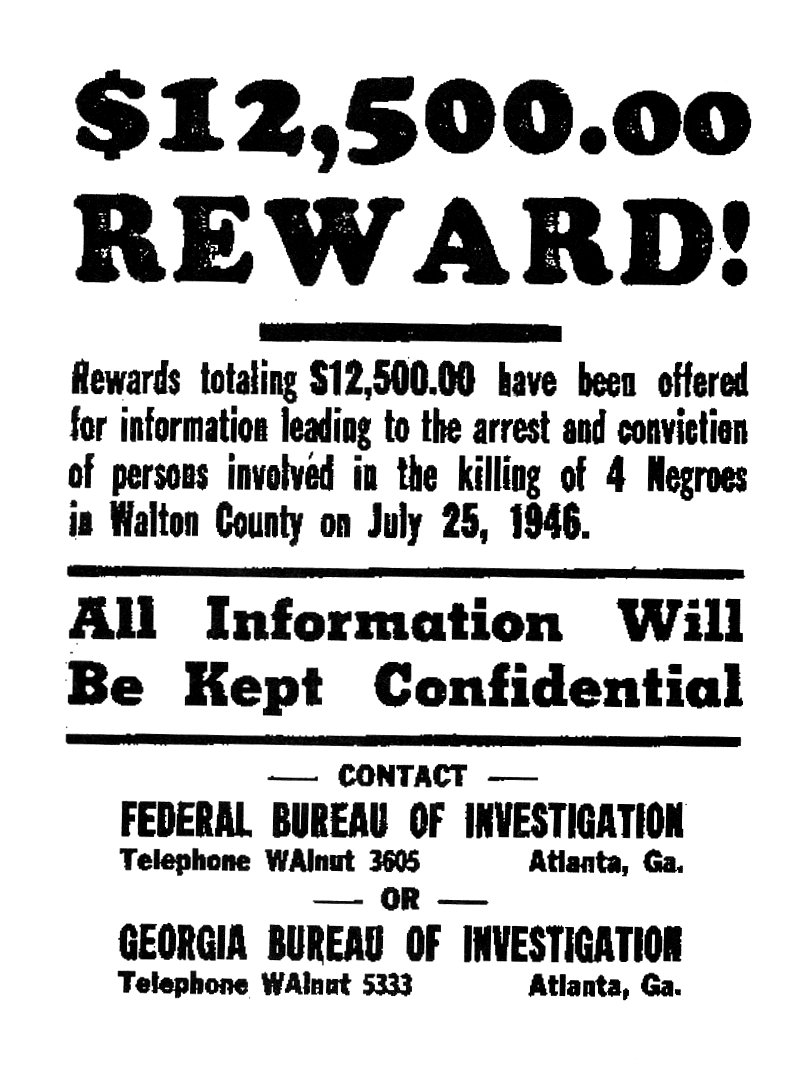

The public nature of this attack gained national press attention. In Georgia, lame-duck Governor Ellis Arnall, recently defeated in a bid for a second term in the 1946 Democratic gubernatorial primary race because of his limited support of African American voting rights, pushed the Georgia Bureau of Investigation to assist local authorities in a search for the killers. National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) leaders rallied public attention to the crime to force action by the federal government. Ultimately, U. S. President Harry Truman offered a $12,500 reward for information and directed the Federal Bureau of Investigation to take action in the case. Truman later referenced the Moore’s Ford lynching as influencing his decision to create the President’s Committee on Civil Rights and to integrate the military in 1948.

Despite these actions, there were no prosecutions for the crime committed at Moore’s Ford. FBI investigators gathered shell casings and bullets from the tree where the four sharecroppers were executed but found no witnesses willing to testify as to the identities of the perpetrators, even though at least fifty-five individuals were reported to have participated in the mob action. Walton County convened a grand jury to hear evidence about the crime but no indictments followed. The NAACP, frustrated with the lack of justice and other reports of violence toward servicemen returning from World War II, used the case to promote an anti-lynching bill in Congress but membership in chapters of the NAACP across the South dropped in the 1940s out of fear of retribution from the Klan and the state’s white power structure.

Renewed interest in Georgia’s civil rights struggle brought attention to the Moore’s Ford lynching in the late twentieth century. In the 1960s, civil rights activist Bobby Howard worked with the NAACP to renew calls for justice in the case. The Georgia Bureau of Investigations and the FBI both returned to the case in 2004, questioning many now-elderly witnesses and doing more forensic investigations. These investigations have largely stalled as witnesses maintain their silence about the events of Moore’s Ford.

Yet if the investigations have not produced convictions, ongoing local efforts keep the Moore’s Ford lynchings in public view. In 1997 an interracial group of citizens in Walton County created the Moore’s Ford Memorial Committee to establish a historical marker at the bridge site. Public re-enactments of the lynchings have become an annual tradition in the region, starting in 2005.