In the article below, Dr. Uchenna Umeh, a former San Antonio, Texas physician, briefly describes how mental health among African Americans was viewed and treated by the American medical community from the antebellum period until today. In the process she describes how those attitudes have impacted black views of mental health into the contemporary era.

In 1848 John Galt, a physician and medical director of the Eastern Lunatic Asylum in Williamsburg, Virginia, offered that “blacks are immune to mental illness.” Galt hypothesized that enslaved Africans could not develop mental illness because as enslaved people, they did not own property, engage in commerce, or participate in civic affairs such as voting or holding office. This immunity hypothesis assumed according to Galt and others at that time that the risk of “lunacy” would be highest in those populations who were emotionally exposed to the stress of profit making, principally wealthy white men.

If indeed this statement were true, then I, a woman of Nigerian ancestry living in the United States—as well as some of my family members, friends and acquaintances, my patients, their parents and grandparents, all black—should never have struggles with mental health issues. Yet we all have. Unfortunately, we of African ancestry have subconsciously embraced and propagated this narrative much to our detriment believing as if this problem does not exist in our race.

In September of 2018, I quit my job as a physician to focus on public speaking, with the sole purpose of increasing awareness about mental illness among people of African ancestry in the United States. I had become aware of a substantial increase in depression and suicidal ideation in my patients. The more I researched this topic, the more I noticed that the problem is increasingly prevalent in the contemporary community. Today suicide rates in African American children aged 5-11 years have increased steadily since the 1980s and are now double those of their Caucasian counterparts. Black men made up 80% of attempted suicides among African Americans in 2015, and in the US, black males are three times more likely to complete suicide than black women. These numbers are on the rise.

Mental illness has been in existence as long as humans have inhabited the earth, but for people of African descent, little or no references are available about this condition before the 1700s. Dr. Benjamin Rush, the leading medical authority in the nation during the years immediately following the American Revolution, was also the most prominent medical practitioner to disagree with John Galt’s ideas about the absence of mental illness among black slaves, when he wrote that many of the enslaved suffered from “abnormal behaviors” including “negritude,” which he described as the irrational desire by blacks to become white. Since becoming white could only be accomplished by miscegenation, Rush argued against intermarriage between races to ensure that negritude would not spread beyond the black population. While there was no indication that he ever treated anyone for this disease, he noted in one of his writings that “the Africans become insane… soon after they enter upon the toils of perpetual slavery in the West Indies.”

Other antebellum medical researchers promoted conditions such as Drapetomania, a disease that caused enslaved blacks to flee their plantations, or Dysaethesia Aethiopia, a disease that purportedly caused a state of dullness and lethargy, which would now be considered depression. Modern historians of slavery have described both conditions as understandable responses to enslavement, but white medical practitioners at the time assumed they were manifestations of mental illness.

Dr. Samuel Cartwright, a pro-slavery physician who worked with enslaved people in Louisiana, argued that severe whipping was the typically the best “treatment” for both conditions. Cartwright and others often reported that Drapetomania and Dysaethesia Aethiopia were often accompanied by skin lesions, which historians now argue were most likely scars from the whippings. In other words, these physicians failed to recognize the connection between the emotional states of the enslaved and the treatment they recommended for their condition.

Most pre-Civil War mental health facilities in the South usually barred the enslaved for treatment. Apparently mental health experts believed that housing blacks and whites in the same facilities would detrimentally affect the healing of the whites. Housing conditions in Southern asylums for the few that accepted the enslaved were bad enough for white patients, but the blacks were often housed outdoors near these institutions or in local jails. There were accounts of some child-slaves being cared for in the yards of the asylums. Most of these facilities were run without government funding or oversight, and inmates, as the children were called, were regularly misdiagnosed and wrongly accused of crimes, extending their stay in these institutions and exposing them to additional mistreatment by authorities. Many of these children were subjected to hard manual labor on farms owned by or near these institutions, foreshadowing the notorious convict leasing systems that sprang up across the Reconstruction-era South.

Often the labor of these children was praised by asylum authorities, further raising questions about the correctness of their diagnoses of mental illness. Here, we catch a glimpse of the possible origin of contemporary black distrust of the healthcare system. In essence, if these slaves were truly “out of their senses,” how were they able to carry out sustained hard labor that required special skills, while white patients were often “too feeble-minded” to work?

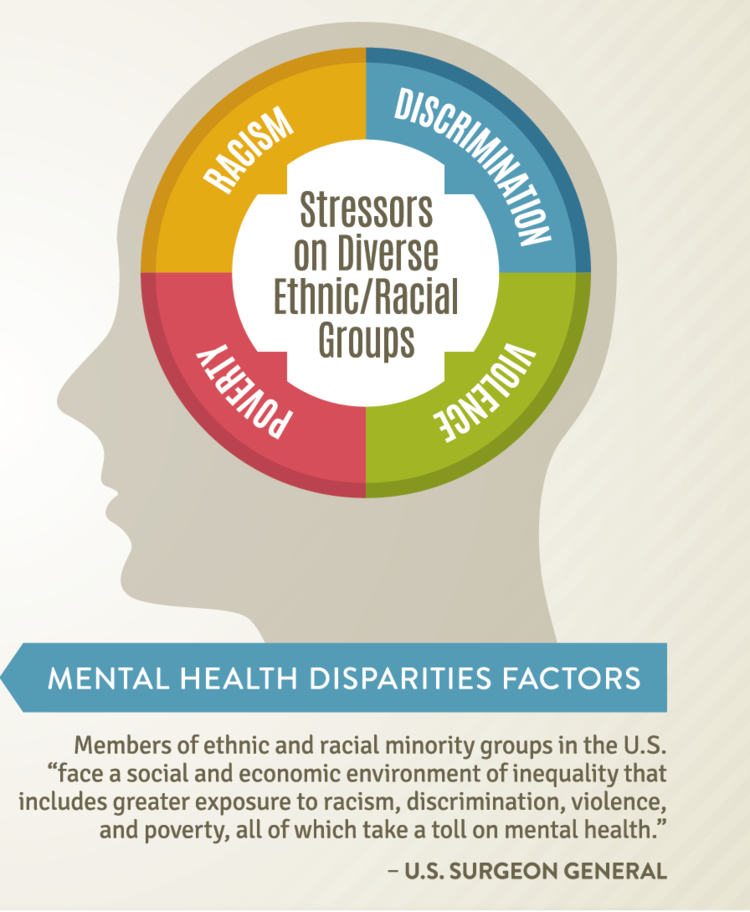

The Civil War freed nearly four million enslaved people across the South. It did not, however, lead to more enlightened attitudes about the treatment of African Americans with mental illness. In 1895, Dr. T.O. Powell, the superintendent of the Georgia Lunatic Asylum observed an alarming increase in insanity and consumption (tuberculosis) among blacks in his state which he attributed to three decades of freedom. Powell argued that when the former slaves got their freedom, it caused them to have little or no control over their appetites and passions and thus led to excesses and vices which in turn generated a rise in insanity. Like medical experts before him, Powell did not factor in socioeconomic conditions including poverty, racial discrimination, and the ever-looming specter of violence (lynchings reached a high point in the 1890-1920 period) as playing any role in the mental state of these freedpeople.

At the beginning of the 20th century African Americans who were said to have mental deficiencies faced a new, more dangerous threat to their well-being, the eugenics movement. Starting in Great Britain, the movement quickly spread to the United States by the 1920s. Eugenics was based on two parallel principles, the encouragement of births among people who were considered “good” genetic stock, and the sterilization of people deemed unfit for reproduction including individuals with mental illness, those who were poor, and those accused of sexual promiscuity and sexual criminality.

Sterilization in the US quickly focused on African Americans. In California alone in the 1930s African Americans who comprised 1% of the population, made up 4% of the victims of legal sterilization. Eventually eighteen states eventually passed laws allowing for the widespread sterilization of the institutionalized including many who were black, misdiagnosed, and falsely accused of crimes. Although sterilization lost some of its appeal when it was discovered Nazi Germany embraced the practice on a wide scale, by the 1970s some states in the South, including notably North Carolina and Alabama, still sterilized disproportionate numbers of black women who were declared by courts to be mentally defective. In North Carolina in the 1960s, for example, more than 85% of those legally sterilized were black women.

African Americans were also victimized by psychosurgery from the 1930s to the 1960s, a process of surgically removing parts of the brain (lobotomy) to treat mental illnesses. Started in Europe, it quickly gained acceptance in the US for reasons that were finally ruled as sociopolitical rather than medical by the late 1970s. Psychosurgery was promoted as a treatment for “brain dysfunction,” a diagnosis claimed to have led to widespread urban violence and inner-city uprisings. While most historians and social scientists viewed urban violence and the uprisings of the 1960s and a reaction to systematic oppression, poverty, discrimination, and state-sponsored physical violence (police brutality), Dr. Frank Ervin, a psychiatrist, and two neurosurgeons, Drs. Vernon Mark and William Sweet argued into the 1960s that this violence was the result of a surgically-treatable brain disorder and promoted their agenda as a specific contribution to ending the political unrest of the period. While never widely accepted and practiced, some lobotomies were performed on black children as young as five years old who exhibited aggressive or hyperactive behaviors.

Postpartum depression (PPD), aka Baby Blues, characterized by feelings of sadness, crying, and hormonal mood swings that happen after birth, also can sometimes be severe and result in anxiety, depression, or rarely, psychosis. The extreme form affects 20% of all races but more than 40% of African American women have been afflicted by it. The reasons vary including lower socioeconomic status, emotional and financial distress, domestic violence, poor access to healthcare, single parenthood, and poor or inadequate childcare. Although rarely mentioned in the mainstream news, PPD is another manifestation of mental illness in African American women.

Sadly, the story of African American mental illness cannot be told without recognizing ever-present sociopolitical agendas, and their particularly pernicious effects on black children. Extreme, concentrated poverty, for example, continues to impact the availability of mental health treatment. In 1983, one in two black children lived in poverty compared to one in seven white children. Today the ratio for black children is still one in three and for white children it is an average of one in ten; Latinos have an average of one in four. Since we now know the mental health of any child is intricately connected to the social, political and economic policies and conditions of their immediate and extended environment, it is little wonder that we continue to see high suicide rates among black children. Racism, systematic oppression and discrimination, police brutality, low socioeconomic status, untreated parental psychopathology, and disruptive family dynamics all influence mental illness in children. With inequality of care, these numbers for black children will only continue to grow.

If medical racism affected the mental treatment of African Americans well into the 20th century, by the end of the century medical practitioners were beginning to recognize the various socioeconomic factors that impact black mental health. Yet cultural beliefs among African Americans also impact attitudes toward and treatment of mental health in black communities. Myths like “it does not happen to us,” “we are strong and therefore do not get depressed,” “our God is able,” “it is not our portion,” and “we can pray it away” are not simply misleading beliefs, they often create unnecessary barriers and stigmas to recognizing and treating mental illness among African Americans.

Though the African American church has been a formidable force for the survival of blacks in a United States still grappling with the residual effects of white supremacy, one must not underestimate the mental toll that can result when, on one hand, the church teaches forgiveness, and on the other hand, victims and their families often have been called upon to repress justifiable feelings of anger and outrage in order to forgive. This becomes a particular challenge when no support infrastructure exists to acknowledge wrongdoing or set a proper stage for reconciliation and justification of the forgiveness.

The crimes of oppression, terrorism, and racism continue against black people even into the 21st century. These factors cannot be overlooked as underlying causes for the rising number of African American suicides. Black women and men who commit suicide may seemingly prefer an afterlife better that the current one with minimally-attractive and viable options. While low socioeconomic status can fuel the prevalence of mental illness, even amongst the more affluent African Americans, stigma remains a strong deterrent to the acknowledgement and acceptance of its presence. Additionally, we are often not treated equally by medical practitioners even when we do seek care and have the resources to pay for that care.

I hope this article will initiate the much-needed conversation among and about blacks on the need for the silence and stigma about mental illness to end. We must engage in the accurate narratives, so we can gain access to appropriate funding, and get on the proper path to healing ourselves, our children, and sustaining our future.