Lois Leveen occupies an unusual role as both historian and novelist. Leveen is the author of The Secrets of Mary Bowser, which is based on the true story of a black woman who became a Union spy in the Confederate White House during the Civil War. Very few details about the historic Mary Bowser can be proven, and many ostensibly nonfiction, scholarly accounts of her life make claims that are either untrue or at least undocumented. Although The Secrets of Mary Bowser is a work of fiction, Leveen has also done substantial research on the “real” Mary Bowser, including debunking many of the claims about her. In this article, originally published on TheAtlantic.com under the title “The Spy Photo That Fooled NPR, the U.S. Army Intelligence Center, and Me,” Leveen explains how “a story of a mistaken identity reveals a lot about the history of black women in America, the challenges of understanding the past, and who we are today.” Leveen and BlackPast.org thank the editors of The Atlantic for allowing us to share this piece here. Readers interested in learning more about the real Mary Bowser should consult the Encyclopedia Virginia entry about her, also written by Leveen. Students and scholars interested in doing their own original research on Bowser can begin by exploring what Leveen describes as the most promising areas for further research. This is a wonderful opportunity to practice real research techniques and to increase our collective understanding of the how black women have contributed to the history of the United States.

It’s a blurry image. But in some ways that makes it the perfect portrait of Mary Bowser, an African American woman who became a Union spy during the Civil War by posing as a slave in the Confederate White House. What better representation of a spy who hid in plain sight than a photograph whose subject stares straight at the viewer yet whose features remain largely indecipherable? Small wonder the photograph has been circulated by NPR, Wikipedia, libraries, history projects, and in my book, The Secrets of Mary Bowser. There’s only one problem: The woman in the photograph was no Union spy. How did we get it so wrong?

Mary Bowser left behind a sparse historical trail. One early clue comes from a 1900, Richmond, Virginia, newspaper story about a white Union spy named Elizabeth Van Lew. In the story, the reporter included the tantalizing detail that before the war, Van Lew freed one of her family’s slaves and sent her North to be educated. The young woman later returned to Richmond and was placed in the Confederate White House as part of Van Lew’s spy ring. Van Lew’s own Civil War-era diary describes her reliance on an African American referred to only as Mary, who was a key source for Van Lew’s intelligence network. Nearly half a century after the war, Van Lew’s niece identified the black woman as Mary Bowser, a revelation included in a June 1911 article in Harper’s Monthly.

Numerous books and articles repeated the tale of Bowser’s espionage, often embellished and without any verifiable sources. The advent of the Internet made it especially easy for the story to circulate, and a growing interest in black history and women’s history provided a steady audience for pieces about Bowser. Online pieces about Bowser could easily include an illustration — if one could be found.

The story of the mistaken Mary Bowser reveals how an interest in history, especially women’s history and black history, can blind us to how much about the past remains unknowable.

As far as I can determine, the photograph began circulating in 2002, when Morning Edition ran a story about Bowser, and NPR included the photograph on their website, with a caption crediting it to “James A. Chambers, U.S. Army Deputy, Office of the Chief, Military Intelligence.” A radio network might seem an unlikely venue for circulating a photograph, but NPR webpages are rife with images supporting each radio story, a fact that exemplifies the extent to which the Internet has made accessing and distributing visual content not only easy but seemingly necessary. (Try to find a popular, public-facing web page without any visuals.)

When my publisher, HarperCollins, asked for images to include in my novel, I dutifully sent the picture purportedly of Bowser. With photographs of Van Lew, Jefferson Davis, and other Civil War figures easy to find, it seemed only fair to feature a picture of Bowser herself. Cautiously, I captioned the image as “rumored to be of Mary Bowser.” Ultimately, I couldn’t resist the urge to show what Bowser looked like, even though elements of the photograph had always troubled me.

As historian and expert on internet hoaxes T. Mills Kelly warns, we should be skeptical about any Internet source that fills a gap in the historical record too neatly. What was the likelihood that a woman for whom we have no birth or death dates, who used several aliases throughout her life, and who lived during the earliest decades of photography, happened to leave a clearly documented studio portrait?

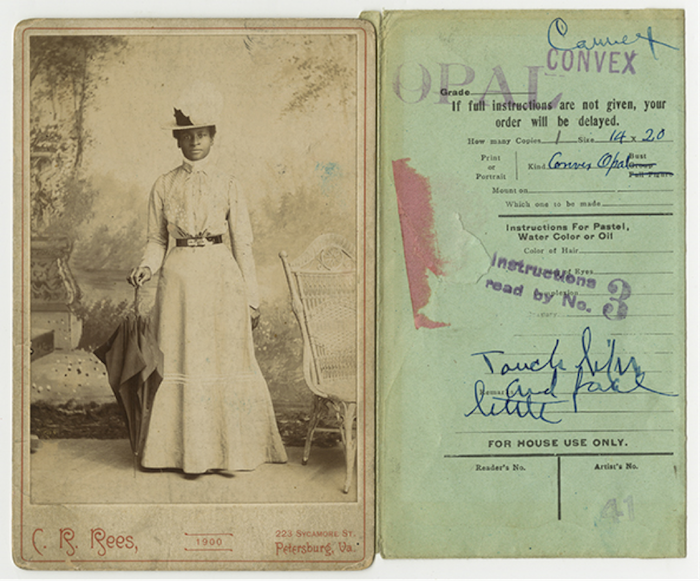

My doubts about the image grew when I unearthed several post-war sources corroborating Bowser’s participation in the Richmond espionage ring. One of these documents indicates that in June of 1867, the slave-turned-spy, then using the surname Garvin, left the U.S. for the West Indies; after that date, she disappears from the historical record. But both the dress the figure in the photograph wears and the chair next to which she stands appear to be from a much later period. Could the only surviving portrait of Bowser really have been taken years, perhaps decades, after the woman herself otherwise seems to have vanished?

Diligence, doubt, and dumb luck — the great triumvirate of historical research — finally led me to an answer. In 2011, I’d contacted both NPR librarian Kee Malesky and the military office listed in NPR’s original caption for the photograph, but neither could provide any information about the image. Despite this seeming dead end, I kept seeking the original, and in January of 2013, I mentioned the mysterious provenance of the photograph to Paul Grasmehr, reference coordinator at the Pritzker Military Library. He put me in touch with Lori S. Tagg, command historian for the Military Intelligence Hall of Fame, which inducted Bowser in 1995. Tagg searched their records and determined that “the Bowser photo most likely came from … the Virginia State Library Pictures Collection.”

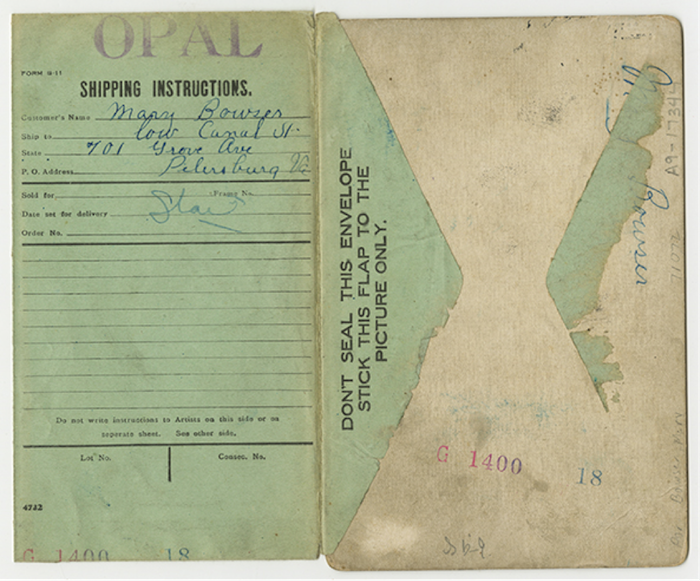

This lead didn’t initially seem promising. Now known as the Library of Virginia, this institution contains no reference in its catalog to an image of Bowser. But when I contacted Dana Puga in their Prints and Photographs Collection, she confirmed that the famed photograph was indeed on file in the library, “in the form of a cabinet card from the Petersburg Studio [of] C. R. Rees.”

Quick research (on the Internet, I confess!) revealed that C. R. Rees took his first picture — a daguerreotype — around 1850. Cabinet cards began to be produced in the 1860s, suggesting a slim possibility that Mary Bowser might have posed for one. But C.R. Rees didn’t open a studio in Petersburg, Virginia, until around 1880, making it unlikely any image captured there was of my spy. Luckily, a few months later a speaking engagement at the Museum of the Confederacy brought me to Richmond, Virginia, where I could at last view the elusive original.

This is the moment a historian lives for — cradling a rare primary source in hand. And it was just as informative as I’d hoped. On the back of the cabinet card was written the name Mary Bowser, and the name was repeated on the attached mailing envelope, along with a street address in Petersburg.

So could this be my spy after all? The answer became clear when I turned the cabinet card over:

There, staring straight at the camera, was Mary Bowser, her features easily recognizable — unlike the blurry version found online. Just as clear was the date the image was created: 1900. A better match for the clothing and furniture, but not for the spy, who by the turn into the twentieth century would have been about sixty years old. The image is of Mary Bowser … just not the Mary Bowser we’ve been claiming her to be.

Having my suspicions about the photograph’s authenticity confirmed left me more frustrated than vindicated. It doesn’t take any advanced training to look at a clearly dated artifact and ascertain whether it could reasonably relate to a figure whose active moment in history occurred decades earlier. Whoever cropped the image to the form in which it recurs online removed a critical piece of historical evidence. But the ease with which NPR, US Army Intelligence, and I have all participated in the mistaken circulation of this image also reveals how much our expectations of history are products of the way we live in the 21st century.

As a current exhibit at the Metropolitan Museum of Art reminds us, the Civil War was more or less contemporaneous with the advent of photography, resulting in an unprecedentedly visual experience of the conflict, even for Americans who never ventured anywhere near a battlefield. The subsequent century and a half of technological advances in capturing and reproducing images have so substantially increased our expectation — our demand — for reliable, historic visual sources that it can be difficult for us to understand how ahistoric this desire is. But in Mary Bowser’s own era, individuals didn’t have our expectations of visual certainty. They were far less likely to know what someone, even a public figure, looked like, as contemporary descriptions of Bowser reveal.

A reporter for the Brooklyn Eagle who attended a lecture the former spy gave in September of 1865 described her as so “strongly resembling” the prominent abolitionist speaker Anna Dickinson that “they might, indeed, easily be mistaken for twin sisters.” Given that Anna Dickinson was white, this description suggests that the speaker was light enough to pass. Yet when Mary first returned to Richmond in 1860, she was arrested for going out without a pass, indicating that she was visually recognizable as “colored” and therefore assumed on sight either to be a slave in need of a pass or a free black in need of proof of her legal status. And when she happened to meet Charles Beecher and Harriet Beecher Stowe in 1867, Beecher described her as “a Juno, done in somber marble … Her complexion was a deep brunette, her features regular, and expressive, her eyes exceedingly bright and sharp.”

How are we to understand these contradictory sources? In an era in which photography was still in its infancy, it was rare to have a detailed sense of what someone beyond your immediate acquaintance looked like. The allusion to Anna Dickinson likely made sense to readers of the Eagle not as a specific physical description of the former intelligence agent but simply as a marker for the still unusual spectacle of a female speaker addressing an audience on political issues of the day. Although by our standards it might be regarded as an inaccurate comparison, the Eagle’s description filled an expectation specific to its era, just as the photo purportedly of Bowser filled an expectation specific to our own era.

Bowser’s story evidences the wonderful truth that Americans of all backgrounds contributed to our history. But the enormous holes in what we have of her biography remind us that gender, race, and class also shaped how millions of Americans went unrecorded in what we rely on as the historical record, because they were restricted from holding property, voting, leaving wills, or being accurately recorded in censuses. Wanting to commemorate an African American woman who played such a dramatic part in the Civil War is laudable. Expecting to have a photograph of her was borderline ludicrous. (Consider that even what seems to most Americans today like basic information about the Civil War, the number of military deaths during the conflict, remains a matter of estimation and conjecture.)

The story of the mistaken Mary Bowser reveals how an interest in history, especially women’s history and black history, can blind us to how much about the past remains unknowable. The paradox of the information age is that our unprecedented access to information feeds an expectation that every search will yield plentiful — and accurate — results. But the type of evidence that our 21st-century sensibilities most desire may be the least likely to exist.

Uncovering the past is arduous work: Compare the ease with which an Internet search turns up the falsely labeled, cropped image of Mary Bowser with the number of sources I persistently contacted over a period of several years before locating the original cabinet card. Alas, in the age of the Internet, it may prove nearly impossible to curtail the use of that image as an avatar for the elusive slave-turned-spy, despite the definitive proof that it isn’t her.

Probing how our own desires shape our understanding of history can be revelatory. If a genie granted me the ability to learn any three things about Bowser, I wouldn’t choose what she looked like — it’s not nearly as important as understanding the choices she made that led to her extraordinary espionage, the dangers she faced in that position, or how she understood her own role in the struggle to end chattel slavery. But in telling her story, I admit I still find it hard not to want to offer a visual image, to present her in the way that is so quick, and so ubiquitous, today.