In the following article University of Oregon historian Daniel Pope briefly outlines the history of African Americans in the Advertising Industry since the beginning of the 20th Century.

Paul Kinsey, a young white copywriter at a prominent advertising agency in 1961 dates an African American woman and even accompanies her South to register voters. His coworkers find the relationship troubling and bewildering. Their treatment of the woman ranges from condescension to blatant hostility. With the exception of a few white ethnic “creative” staff, the agency is solidly white Anglo-Saxon Protestant.

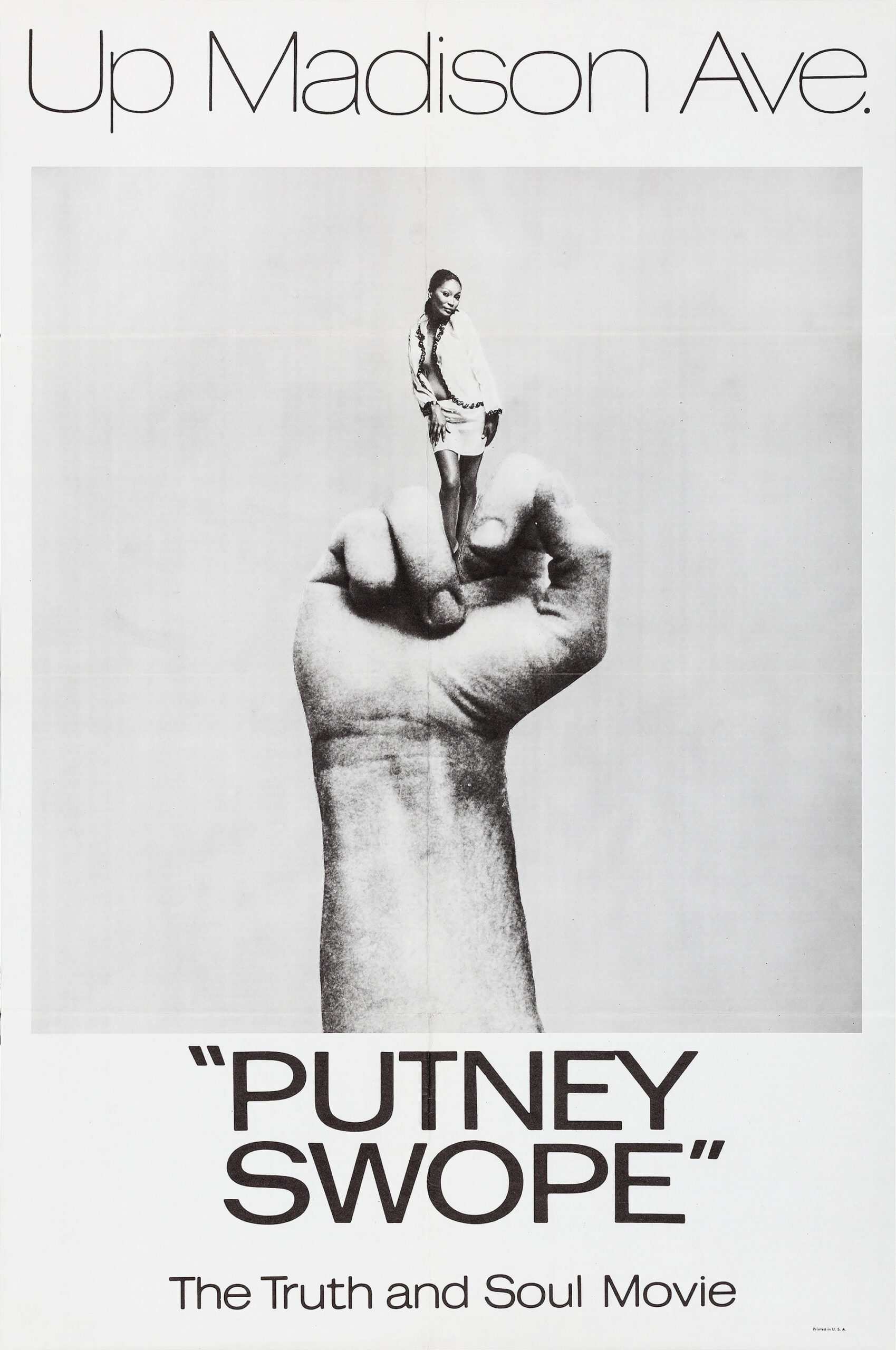

At a board meeting, the head of a Madison Avenue advertising agency collapses and dies. Stunned, the board members inadvertently elect the token African American, Putney Swope, to run the agency. Renaming the firm Truth and Soul Advertising, Swope and a ragtag gang create outrageous but appealing advertisements that keep viewers glued to their TV sets–but unwilling to tear themselves away to go out and consume. In the end, the United States government embarks on a campaign to destroy the agency as a subversive threat.

These two fictional vignettes, the first from the television series Mad Men, the second from the 1969 movie Putney Swope, suggest the degree of change (and the resistance to change) in the position of African Americans in the advertising business in the 1960s. That decade, as we shall see, was a turning point, but the turn was incomplete and problems of exclusion and discrimination remain four decades later.

Advertising has long played a central role in American business and culture, with estimated 2010 expenditures over $160 billion. The American advertising industry’s relationship with African Americans has long been troubled. Until a generation ago, advertisements rarely depicted African Americans in anything but menial positions or demeaning stereotypes. Although portrayals have changed in recent decades, African Americans are significantly underrepresented in the ad industry’s professional and managerial positions. From the 1920s on, a few African American pioneers established agencies to sell to the “Negro market” but inclusion in the industry’s mainstream has come painstakingly slowly. Experts assert that the scarcity of black faces in major advertising agencies has limited corporate America’s efforts to market to people of color. This article focuses on African Americans in the advertising business, but readers should bear in mind that the limits on their influence within the industry affects racial themes in the publicity we see and hear.

Early in the twentieth century, African American newspaper publishers faced the need to solicit advertising to support their often-struggling publications. Here a handful of African Americans began to enter the advertising industry. Claude Barnett, a Tuskegee Institute graduate and advocate of Booker T. Washington’s self-help doctrines, began an advertising agency in Chicago, adopting the slogan, “I reach the Negro.” Barnett’s main success, however, came not as an agent for advertisers but as a seller of advertising space in the African American press. Eventually, he sold his firm during the Great Depression but Barnett continued to push national advertisers to recognize the buying power of black consumers and to reach them through the African American press.

Several others followed in Barnett’s path, stimulating interest in advertising to African Americans. Among these pioneers, there was controversy about whether African American consumers would respond to the same appeals as whites, but white-owned ad agencies before World War II almost never considered making differentiated appeals to the dimly-perceived “Negro market” and effectively excluded African Americans from professional and managerial positions in their firms. David Sullivan, who opened an advertising agency in 1943, reminded marketers that one in ten Americans was a Negro and warned white firms against offensive racist portrayals. Although he won respect for talent and knowledge of the African American market, Sullivan had to close his business in 1949 and spent the next fifteen years unsuccessfully searching for a position in a mainstream agency.

Before mid-century, few corporate marketers recognized the purchasing power of African Americans. Pepsi Cola, Beech Nut Gum, and Pabst Beer were among the earliest consumer product manufacturers appealing to black consumers. In the same years, a very few African American forerunners entered major advertising agencies. Advertising industry historian Jason Chambers, in his comprehensive and invaluable study, Madison Avenue and the Color Line, refers to these men–they were all men–as “Jackie Robinsons,” but the phrase may be misleading. Robinson’s entrance into Major League Baseball in 1947 soon opened doors to large numbers of African Americans. The advertising vanguard remained highly exceptional for many years.

It is worth remembering that advertising agencies were, even by the low standards of the early twentieth century, highly exclusionary and resistant to diversification. Thus a 1931 “Who’s Who in Advertising” volume could casually note, “Adherents to the theory of Nordic supremacy might relish the fact that blue-eyed advertising men are in the majority.” The homogeneity of the industry produced advertising that stressed conformity and disregarded diversity. Images of African Americans rarely appeared. Agencies and their corporate clients took it as given that white consumers would not buy products associated with African Americans.

During the 1960s, advertising underwent a “creative revolution.” The business opened its doors to many Jews, Italian-Americans, and other “white ethnics” and advanced some women to leadership positions. There was a sharp change in advertising styles. Irony and irreverence characterized prizewinning campaigns for major brands like Alka-Seltzer, Volkswagen, and Avis. This reflected both the new blood entering the industry and new marketing strategies. The concept of market segmentation called for advertising aimed at consumer groups with distinct demographic characteristics. The “mass market,” almost invariably assumed to be white, diminished in importance.

To tap the buying power of African American consumers and to broaden the talent base of the industry, some mainstream agencies began to look for African American “creatives.” Meanwhile, broader social developments–both the moral and political triumphs of the civil rights movement and the assertions of pride and identity in the Black Power movement–created preconditions for more progress in the advertising industry. Major civil rights organizations, notably the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and the Urban League, pressed the advertising industry to improve the image of African Americans in ads and to take affirmative action to hire qualified African Americans. It is not surprising that the movement would focus on advertising. As historians Robert Weems, Lizabeth Cohen, and Jason Chambers have pointed out, the civil rights movement demanded entrance into America’s consumer society. The right to spend one’s money where one chose and the right to partake of consumer products and services on equal terms with white consumers were at the heart of the movement’s demands. Myrlie Evers, widow of martyred Mississippi NAACP leader Medgar Evers, endorsed this approach: “Negroes want to share this life. They want to join the affluent society, not overthrow it.”

Of the two main demands on the advertising industry, the movement was more successful in gaining positive images of African Americans in advertising than in promoting broad inclusion in the suites and offices on Madison Avenue. Industry spokesmen contended that there were few qualified African American candidates for creative and managerial positions in advertising. In some cases, the industry’s “pipeline” claim sought to excuse the slow pace of African American hiring. Sometimes, however, it stimulated the development of recruitment and training programs to prepare young men and women for advertising careers. The most successful was the Basic Advertising Course that trained as many as half the black professionals entering the industry in Chicago in the late sixties. However, that course’s success was not replicated elsewhere. The U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission found in 1968 that New York’s African American white collar employment in advertising was 2.5% of the total. In the city as a whole, 5.2% of the white collar labor force was African American. Moreover, most of those working in advertising were below management level.

In the late sixties and early seventies, African American professionals were opening a new cohort of black-oriented agencies. Although some were short-lived, UniWorld, founded in New York in 1969, and Burrell Communications, a Chicago-based firm since 1971, have grown into significant forces in the advertising industry. Both are aligned with broader networks of advertising agencies. They differ in their strategies. UniWorld portrays itself as the leader in marketing to African Americans and Latinos. Burrell focuses on African American consumers but also promotes its campaigns aimed at the “new general market.”

A generation after the “Golden Age” of the late sixties, attention has once again focused on the underrepresentation of African Americans in the advertising business. The 2000 census counted more than half a million workers in advertising and related fields, only about 6% were African Americans. In 2006, the New York City Commission on Human Rights scheduled hearings on discrimination on Madison Avenue. African American media sharply criticized the industry’s record, as did a few voices with the advertising business. That fall, fifteen large New York agencies signed agreements to formulate goals for hiring minorities over the next three years; the Commission canceled its hearing plans. Most of the plans, revealed the following January, were ambitious, calling for substantial increases in managerial and professional hiring. Nevertheless, discontent remained high.

In January 2009, the NAACP launched its Madison Avenue Project in conjunction with the civil rights law firm of Mehri & Skalet, aiming “to reverse the widespread, entrenched discrimination against African American professionals employed in the advertising industry.” They presented a detailed economic consultants’ report that found African American college graduates in advertising were earning only 80% as much as their equally-qualified white colleagues. African American representation in managerial and professional positions, at 5.3%, was barely more than half the level to be expected from Census Bureau and EEOC data. The study noted other signs of persistent discrimination as well. A year later, in February 2010, attorney Cyrus Mehri announced he was filing discrimination charges with the EEOC against leading advertising agencies. This was seen as a step toward initiating a class action suit against the industry.

Early in the twentieth century, as the nation’s consumer culture flourished, a few African Americans were able to gain a toehold in the advertising industry. After mid-century, the civil rights and Black Power movements hastened the pace of acceptance and gave rise to businesses where African Americans could successfully appeal to the African American market. The decline in overtly racist portrayals in advertisements accompanied the partial integration of the advertising industry. Still, the pace was halting. Thus, nearly half a century after the advertising industry’s first measures to rectify a pattern of exclusion and discrimination, dissatisfaction with the pace of progress and doubts about the industry’s commitment to racial equality in the workplace remain serious concerns.