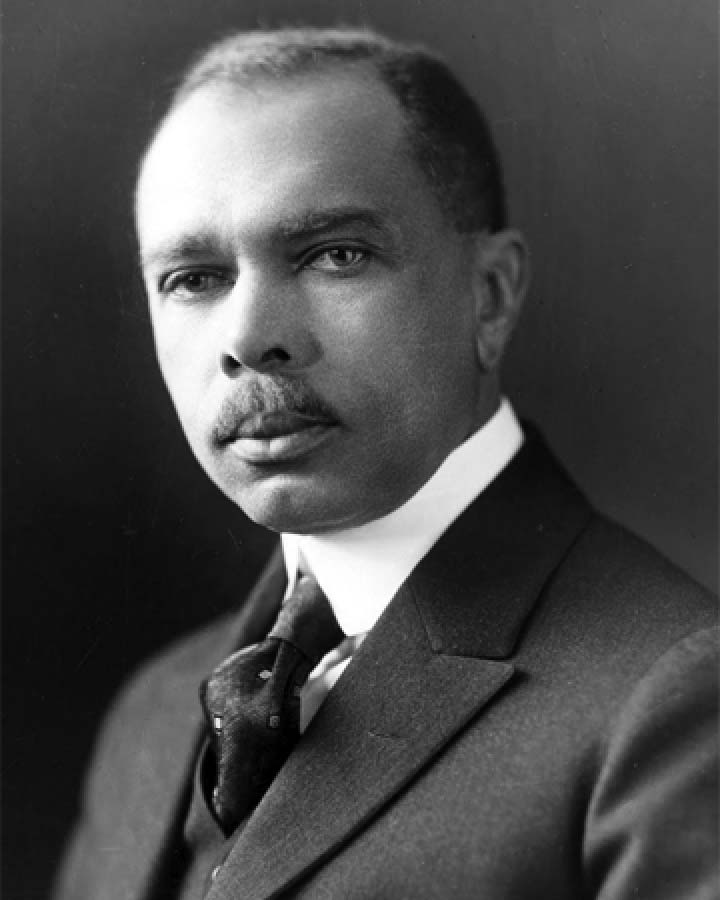

James Weldon Johnson, composer, diplomat, social critic, and civil rights activist, was born of Bahamian immigrant parents in Jacksonville, Florida on June 17, 1871. Instilled with the value of education by his father James, a waiter, and his mother Helen, a teacher, Johnson excelled at the Stanton School in Jacksonville. In 1889, he entered Atlanta University in Georgia, graduating in 1894.

In 1896, Johnson began to study law in Thomas Ledwith’s law office in Jacksonville, Florida. In 1898, Ledwith considered Johnson ready to take the Florida bar exam. After a grueling two-hour exam, Johnson was given a pass and admitted to the bar. One examiner expressed his anguish by bolting from the room and stating, “Well, I can’t forget he’s a nigger; and I’ll be damned if I’ll stay here to see him admitted.” In 1898, Johnson became one of only a handful of black attorneys in the state.

Johnson, however, did not practice law. Instead, he became principal at the Stanton School in Jacksonville, where he improved the curriculum and also added the ninth and tenth grades. Johnson also started the first black newspaper, the Daily American, in Jacksonville. With his brother Rosamond, who had been trained at the New England Conservatory of Music in Massachusetts, Johnson’s interests turned to songwriting for Broadway.

Rosamond and James migrated to New York in 1902 and were soon earning over twelve thousand dollars a year by selling their songs to Broadway performers. Upon a return trip to Florida in 1900, the brothers were asked to write a celebratory song in honor of Abraham Lincoln’s birthday. The product, a poem set to music, became “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” now known as the Black National Anthem.

In 1906, Johnson became United States consul to Puerto Cabello in Venezuela. While in the foreign service, he met his future wife, Grace Nail, the daughter of influential black New York City real estate speculator, John E. Nail. The couple’s first year was spent in Corinto, Nicaragua, Johnson’s diplomatic post.

While in the diplomatic service, Johnson had begun to write his most famous literary work, The Autobiography of An Ex-Colored Man. This novel, published in 1912, became a work of note during the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s. In 1914, Johnson became an editor for the New York Age. He soon gained notoriety when W.E.B. DuBois published Johnson’s critique of D.W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation in the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) publication The Crisis. Johnson was a member of Sigma Pi Phi Fraternity and Phi Beta Sigma Fraternity.

In 1916, Johnson became Field Secretary for the NAACP and dramatically increased NAACP membership and the number of branches. In 1917, he organized the famous “Silent March” down 5th Avenue to protest racial violence and lynching. The march, which numbered approximately ten thousand participants, was the largest protest organized by African Americans to that point. Johnson’s participation in the campaign against lynching continued for the next two decades.

Although he was a nationally recognized civil rights leader, Johnson continued to write and critique poetry in a column for the New York Age. His “Poetry Corner” column, published in 1922 as The Book of American Negro Poetry, became an important contribution to the emerging Harlem Renaissance particularly because of its inclusion of Claude McKay’s “If We Must Die.” Johnson’s other Harlem Renaissance contributions included The Book of American Negro Spirituals (1925), God’s Trombones (1927), and Seven Negro Sermons in Verse (1927).

In 1930, Johnson published Black Manhattan, a Social History of Black New York, and three years later (in 1933) his autobiography, Along This Way, appeared.

Johnson resigned from the NAACP in 1930 and accepted a faculty position in creative writing and literature at Fisk University. He maintained an active life in teaching and public speaking until he died in an automobile accident on June 26, 1938, while vacationing in Wiscasset, Maine. He was 67 at the time of his death.