In the article below social commentator John H. McWhorter challenges the nation to think differently about Black History Month. He argues that the emphasis on black “heroes” negates the tens of thousands of stories of ordinary African Americans who have overcome or outmaneuvered racism and discrimination. Their stories can also provide inspiration for younger generations seeking authentic role models.

It is a mantra among black Americans that we are insufficiently aware of our history, that our advancement will be hobbled until we are all rooted in a sense of continuity with the past. Yet, every year we are regaled with not just a Black History Day but a Black History Month. Over four weeks in February, the media, museums, colleges and universities and others will trot out the usual procession of black pioneers, with blown-up photos of Martin Luther King, Harriet Tubman and Jesse Jackson festooning libraries and churches.

On TV we will see recountings of the brutality and discrimination blacks suffered at the hands of whites: slave ships, lynchings, segregated lunch counters and the beating of Rodney King. And we’ll see the usual screenings of films such as “Stormy Weather,” “Sounder,” “Carmen Jones,” “Roots” and “Glory.” And for the rest of the year black talk-radio will continue to resound with callers decrying black Americans’ lack of exposure to their history. But the problem isn’t so much that blacks aren’t being exposed to enough black history-too often it’s presented the wrong way.

Certainly we must remember our heroes. Yet, an Adam Clayton Powell Jr. or a Mary McLeod Bethune come along only once in a blue moon. We view them in awe, but it can be difficult to see how such people can lead us in our daily lives, especially when so many of them stare at us from sepia-toned photos wearing strange clothes and hairdos.

And then there are the tragedies: Is it really so surprising that black people have a hard time developing a sense of pride after hearing about how they were uprooted from their homes in Africa and brought to the New World where they were humiliated, beaten, maimed and shut out?

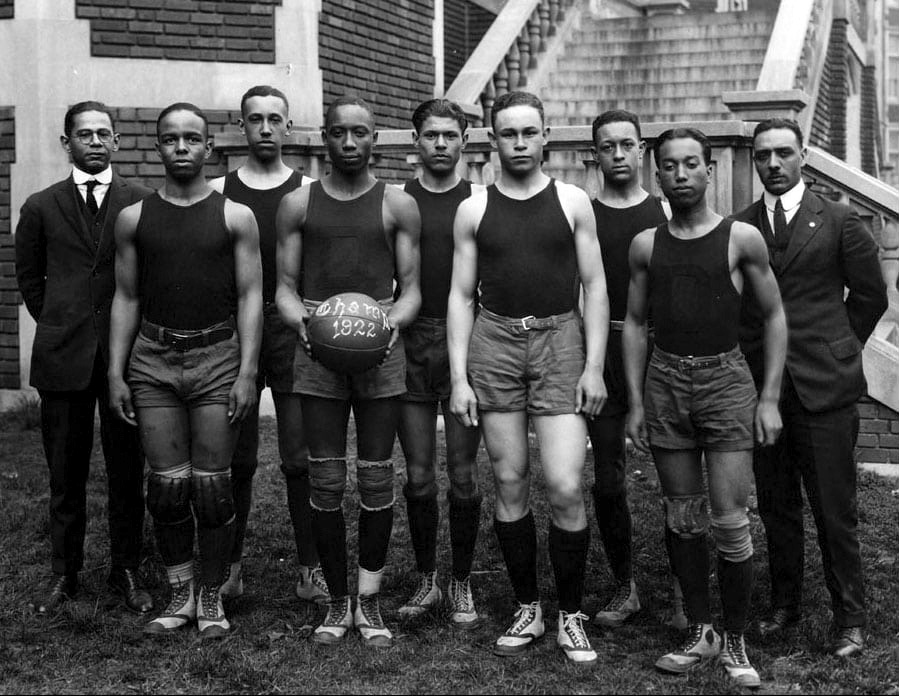

What is missing from this vision is the inspiring successes that ordinary black Americans accomplished long before the Civil Rights movement. These black Americans-none of whom was a hero or thought of himself or herself as such-triumphed despite racism rather than assuming they were powerless until racism disappeared. This kind of black history, while perhaps less glamorous than tales of abuse during slavery, is precisely what blacks would most benefit from as they make their way toward a better future.

Take the Tulsa story. In the early 1900s, black residents of Tulsa, Okla., had developed a thriving business district with all the amenities whites enjoyed on the other side of town- restaurants, hotels, banks, theaters, stores of all kinds. They had done this in a world where racism was more naked than anything all but a very few black Americans experience today. Racism was so intense, that in response to a trumped-up story of a black man making advances toward a white woman, whites burned the district to the ground in 1921 and killed many blacks.

This story has been treated as a warning for blacks to watch their backs because eternal anti-black hostility lies within all whites. But the Tulsa story bequeaths us with a more enlightening message; Ordinary black folks banded together and created an economic base at a time when membership in the Ku Klux Klan was as ordinary for whites as belonging to the Rotarians. It was also a time when blacks had little political power, especially in the South, and unabashed racism was common among whites of all classes and levels of education.

But instead of an inspirational message, blacks are told that they’re powerless to start businesses in their own communities because banks will not give them small-business loans. And, we seldom hear of the Community Reinvestment Act, which pressures banks to make loans to minorities, a measure that has helped many inner-city communities since its enactment in 1977. No matter how pervasive one believes racism is today, there are not marauding white bands attacking blacks who attempt to make economic progress in their communities or any place else in the business world.

Black Tulsa was not built through a once-in-a-lifetime effort by high-paid black superstars. It was led by ordinary folks who made the best of a bad situation. This is the Black History that will be of much more use to us than one more recounting of how much George Washington Carver could do with a peanut.

Here’s another aspect of black history that we are unlikely to hear about during Black History Month or any other time: Before the 1960s, black students in segregated schools often performed at the same level of whites, if not higher –despite paltry budgets and substandard school buildings.

For example, from the turn of the century until the 1940s, black students at Washington, D.C.’s, Dunbar High School performed at or above the national average. Dunbar students were outscoring two of D.C.’s white schools in 1899, just a few decades past slavery and at a time when lynching was a national sport.

Black economist Thomas Sowell has chronicled Dunbar’s success and that of a similar New York City school, only to be accused of advocating “the resegregation of schools” by John Baugh, a black linguist, education specialist and author of “Beyond Ebonics.”

But black scholars would do better to let the past speak to us more constructively. Sowell has pointed out that if all-black schools could bring the best out of black students during a time when our society was overtly hostile to blacks, then they should serve as beacons for the opportunities available today.

And indeed, experimental all-black schools nationwide are demonstrating that we can create modern versions of what Dunbar High once was. In other words, we do not require the presence of whites to excel.

The triumphs of ordinary black folks in Tulsa and at Dunbar High don’t provide the fodder for TV movies. History has forgotten the names of most of the people responsible. But recognizing the fruit of their labor shows what blacks are capable of more eloquently than one more story about the Underground Railroad and larger than-life figures such as Frederick Douglass.

Today, few black Americans would question the wisdom of Du Bois’ call for blacks to strive for success equal to whites rather than remaining satisfied for the time being as artisans and laborers. But this message is no longer inspirational because it can’t be contrasted to Washington’s less-uplifting alternative, which has been largely discredited. Meanwhile, the romantic and unrealistic notion of fleeing to Africa has little to do with the real task confronting black America, which is to stake its claim here in the only nation that will ever be its home.

If Black History Month is to play any meaningful part in black advancement, we should emphasize the positive communal experiences rather than the spirit-crushing setbacks.