When the Emancipation Proclamation went into effect January 1, 1863 African American soldiers in the Union Army had been fighting the Confederacy along the South Carolina coast for nearly a year. On January 1, these soldiers assembled with their families to celebrate. Their commander, Colonel Thomas Wentworth Higginson, had been a Unitarian minister and abolitionist before the Civil War who together with black and white Boston residents had stormed in the city to free black fugitive slaves who had thought they had reach a city where their liberty would be protected. He had also been an active participant in the Underground Railroad and was part of a group that supplied material aid to John Brown just before his ill-fated raid on Harper’s Ferry in 1859. Once the Civil War began Higginson joined the United States Army, was commissioned a Colonel, and rare for the time, specifically requested that he be assigned to a black regiment. He received his opportunity in 1862 when he was sent to the Sea Islands off the coast of South Carolina which was now Union-held territory. This Union occupation freed thousands of enslaved people and some of the men who were former slaves were now trained by Higginson and other officers to become soldiers in that occupying army. Higginson left a diary which recorded these events and eventually became the basis for his best-selling book, Army Life in A Black Regiment, and Other Writings, which was originally published in 1870. In the following excerpt from that book, provided by historian William L. Katz, he briefly describes the January 1, 1863 ceremony which is widely recognized as one of the first celebrations of the Emancipation Proclamation. Katz also includes this description in his book, Eyewitness: The African American Contribution to American History. Higginson’s words appear below:

About ten o’clock the people began to collect by land, and also by water in steamers sent by General [Rufus] Saxton for the purpose; and from that time all the avenues of approach were thronged. The multitude were chiefly colored women, with gay handkerchiefs on their heads….

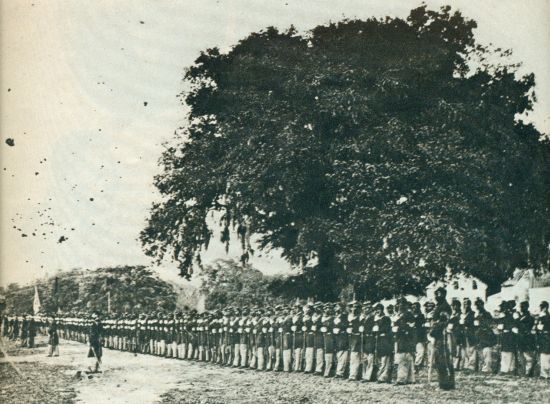

There were many white visitors also, ladies on horseback and in carriages, superintendents and teachers, officers, and cavalry-men. Our companies were marched to the neighborhood of the platform, and allowed to sit or stand, as at the Sunday services; the platform was occupied by ladies and dignitaries, and…the colored people filled up all the vacant openings in the beautiful grove around, and there was a cordon of mounted visitors beyond… Then the President’s Proclamation was read by Dr. W. H. Brisbane, a thing infinitely appropriate, a South Carolinian addressing South Carolinians…. Then the colors were presented to us by the Rev. Mr. French, a chaplain who brought them from the donors in New York.

All this was according to the program. Then followed an incident so simple, so touching, so utterly unexpected and startling, that I can scarcely believe it on recalling, though it gave the keynote to the whole day. The very moment the speaker had ceased, and just as I took and waved the flag, which now for the first time meant anything to these poor people, there suddenly arose, close beside the platform, a strong male voice (but rather cracked and elderly), into which two women’s voices instantly blended, singing, as if by an impulse that could no more be repressed than the morning note of a song sparrow, the song, “My Country, ’tis of thee, Sweet land of liberty, Of thee I sing!”

People looked at each other, and then at us on the platform, to see whence came this interruption, not set down in the [program]. Firmly and irrepressibly the quavering voices sang on, verse after verse; others of the colored people joined in; some whites on the platform began, but I motioned them to silence. I never saw anything so electric; it made all other words cheap; it seemed the choked voice of a race at last unloosed. Nothing could be more wonderfully unconscious; art could not have dreamed of a tribute to the day of jubilee that should be so affecting; history will not believe it; and when I came to speak of it, after it was ended, tears were everywhere.??