Jacob Vanderpool was the only person known to have been legally expelled from Oregon on the basis of its anti-Black exclusion laws. Born in the West Indies in 1820, Vanderpool was classified in court documents as “mulatto,” likely the descendant of a Dutch plantation owner and an enslaved African woman. Vanderpool moved to New York as a young man, where he married and started a family. At the time of his expulsion from Oregon in 1851, Vanderpool had three children with his wife Eliza: four-year-old twins Amelia and Jane, and an infant son, Martin.

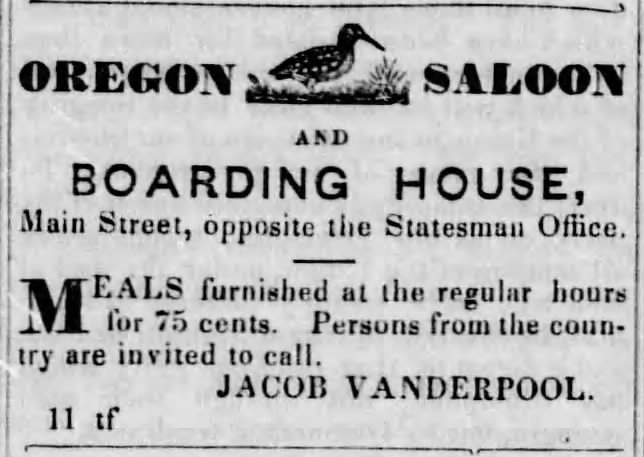

After working as a sailor, Vanderpool arrived in Oregon in 1850, and opened a boarding house in Oregon City, Oregon. Some later sources have placed Vanderpool in Salem, Oregon; the confusion seems to have arisen from the fact that Vanderpool advertised his establishment as being “opposite the Statesman office,” and the Statesman newspaper moved from Oregon City to Salem in 1853. But in 1851, when Vanderpool’s ad ran, and when the court case against him occurred, the Statesman office and Vanderpool’s business were located in Oregon City.

Vanderpool’s first ad ran in the paper on June 6, 1851. The following month, in July, Theophilus Magruder took ownership of the nearby Main Street Hotel. Among Magruder’s long-term guests was Thomas Nelson, the Chief Justice of the Oregon Territory Supreme Court. Nelson wrote home describing how much he appreciated the extra attentions of his new landlord. One month after that, the Chief Justice would hear the case in which his attentive landlord, Theophilus Magruder, pressed charges against his business competitor Jacob Vanderpool.

Vanderpool’s defense attorney, Amory Holbrook, made three central arguments. First, he argued, the exclusion law was “in all respects unconstitutional.” Secondly, the prosecution had not proved that Vanderpool was, in fact, “not… one of the persons permitted to remain.” Finally, Holbrook questioned whether the law had been “legally enacted.”

The prosecution did not respond to Holbrook’s arguments. Instead, they called witnesses to establish that Vanderpool had moved to Oregon after 1849, when the law had gone into effect. One witness claimed to have seen Jacob Vanderpool in Philadelphia in 1849. Another witness testified, “I heard him say that he came here last August.” Chief Justice Nelson ruled the following day, on August 26, 1851, that he was “satisfied… that Jacob Vanderpool is a mulatto,” and that his presence in the Oregon Territory was illegal. Vanderpool was given 30 days to “quit the Territory.”

Tax records indicate that Vanderpool returned to New York, where he eventually worked with his teenage son, Martin, as a carriage driver. By 1870, Vanderpool returned West with a second wife, Mary. They settled in San Francisco, where Vanderpool worked as a “packer of hardware” and as a school janitor. He was active with the Young Men’s Union Beneficial Society, a Black activist organization. The last record of Vanderpool’s life is a voter registration taken in 1886, when he was 66 years old.

A handful of other African Americans were tried under Oregon’s exclusion laws, but in each case, their white neighbors successfully petitioned for them to stay. In 1859, Oregon became the only state admitted to the Union with an anti-Black exclusion law on its books. The law was not repealed until 1926.